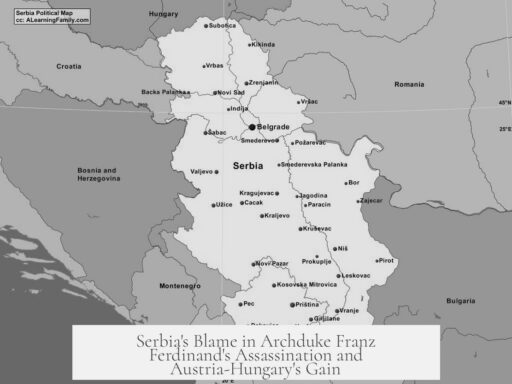

Serbia was blamed for the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand because the assassin, Gavrilo Princip, was a Serbian nationalist linked to the Black Hand, a secret society advocating South Slav independence. Austria-Hungary seized this event as justification to hold Serbia responsible, despite uncertainty over direct Serbian government involvement. This blame served as a pretext for Austria-Hungary to act against Serbia, addressing long-standing concerns about Serbian nationalism threatening imperial stability.

The assassination on June 28, 1914, shocked the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Princip, a Bosnian Serb nationalist, aligned with the Black Hand, killed the heir to the throne. Austria-Hungary swiftly connected the attack to Serbia, considering the Black Hand’s origins and Princip’s nationality. Although historians today question the extent of official Serbian government knowledge or support, the empire treated Serbia as complicit. This granted Austria-Hungary a convenient reason to confront its perceived adversary.

Austria-Hungary faced persistent internal challenges. It ruled a multi-ethnic population fraught with nationalist tensions, especially in the Balkans. The ‘South Slav Problem’ involved Slavic groups pushing for independence or unification, threatening the empire’s cohesion. Serbia was viewed as the focal point of this nationalist agitation. Its encouragement of Slavic nationalism made it a real and symbolic threat to Vienna’s control over its southern provinces.

George Macaulay Trevelyan, a historian, emphasized how Austria-Hungary’s position depended on suppressing Serbia to maintain control. The empire’s repression of Slavs in Bosnia heightened hostility against Serbia, which was seen as a “liberator” to these Slavs. The assassination gave Austria-Hungary the casus belli it needed to launch a decisive strike. By portraying the attack as Serbian-backed, the empire justified military action as a necessary defense to safeguard its territorial integrity.

- The assassination offered Austria-Hungary a chance to tackle the ‘Serbian menace’.

- A victory over Serbia would weaken Slavic nationalist movements within the empire.

- Military action provided a hope to stabilize the worrisome Balkan region.

Some political figures in Austria-Hungary had already long advocated for war against Serbia. The empire saw Serbia’s growing influence as a direct threat to its survival. The Chief of the General Staff, Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf, was among those eager for military action. The Archduke himself had proposed reforms that might have eased tensions, including trialism to give Slavic peoples more representation. His death removed a potentially moderating voice.

Austria-Hungary’s rapid decision to blame Serbia fits a broader pattern of opportunism. The empire aimed to use the assassination as a diplomatic and military lever. Its strategic goal was to suppress Serbia and lessen nationalist agitation that undermined imperial authority. Austria-Hungary’s leadership hoped to restore order by crushing a neighbor seen as the epicenter of unrest.

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Assassin | Gavrilo Princip, Serbian nationalist, member of Black Hand |

| Serbian Government Involvement | Uncertain; likely no full endorsement or knowledge |

| Austria-Hungary’s Motivation | Crush Serbia; stop Slavic nationalist unrest; secure empire’s Balkans |

| Political Climate | Internal ethnic tensions; desire for preemptive war on Serbia |

| Archduke’s Stance | Moderate reforms to integrate Slavs; opposed by some generals |

The blame on Serbia served Austria-Hungary’s strategic goals. It strengthened the empire’s case internationally. The subsequent ultimatum to Serbia escalated tensions, catalyzing the July Crisis and leading to World War I. By framing the assassination as a Serbian conspiracy, Austria-Hungary sought to justify war they had been inclined toward for years.

- Serbia was blamed due to Princip’s nationality and nationalist ties.

- There is no conclusive proof of official Serbian government complicity.

- Austria-Hungary exploited the event to pursue war against Serbia.

- Crushing Serbia aimed to solve ethnic unrest in the empire’s Balkans.

- Archduke’s death removed a potential peace-promoting leader.

Why Was Serbia Blamed for the Assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand? What Would Austria-Hungary Have to Gain from It?

In short, Serbia was blamed because a Serbian nationalist, Gavrilo Princip, carried out the assassination — offering Austria-Hungary a perfect excuse to crush a troublesome neighbor and stabilize its faltering empire. But let’s dive into the tangled web behind this pivotal moment in history, and explore what Austria-Hungary stood to gain.

Picture it: June 28, 1914. The Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, strolled through Sarajevo, only to be shot by Gavrilo Princip, a member of the Black Hand Gang, a secret society of Serbian nationalists. The news lands like a bombshell. Immediately, Austria-Hungary fixates on Serbia, suspecting, rightly or wrongly, that the Serbian government must have been at least partially involved.

The Immediate Finger Pointing: Serbia’s Guilt Assumed

The assassination hits the Austro-Hungarian government like a pin to a balloon. They quickly connect the dots — Princip is Serbian, so logically, the Serbian state must have had a hand in it. The assumption isn’t farfetched, but it’s important to note: the full scope of the Serbian government’s involvement remains murky. Princip and the Black Hand likely acted without official backing, or at least without full knowledge of the Serbian cabinet.

This ambiguity matters, because it shows that the accusation against Serbia isn’t grounded in ironclad proof, but rather suspicion and political opportunity. Austria-Hungary, however, wastes no time in exploiting the incident. Think of it as a geopolitical jackpot: the assassination was the spark needed to justify harsh measures against Serbia.

The South Slav Problem and the Empire’s Deep-rooted Issues

Austria-Hungary had been wrestling with what was famously called the “South Slav Problem” for decades. This was a complex tangle of various Slavic ethnic groups under Hapsburg rule, many of whom longed for independence or unity with Serbia. Serbia, as the leading Slavic nationalist power in the Balkans, was a persistent irritant — a phantom menace threatening to destabilize the empire’s multi-ethnic balance.

Given that, it’s no surprise that when the Archduke was killed, the idea of retaliating against Serbia wasn’t just a knee-jerk reaction. It was a calculated move. A chance to put an end to Serbia’s agitating influence and to crush nationalist uprisings that seemed to grow with every passing year.

Austria-Hungary’s Strategic Game: What Did They Stand to Gain?

“The Empire of Vienna and Buda-Pesth is an anachronism, dependent now upon Prussian arms… it [has become] more than ever essential to the Austrians to prevent the further development of Serbia… lest she should become the liberator of the South Slavs.” — Historian George Macaulay Trevelyan, 1915

That quote says it all. Austria-Hungary viewed Serbia as more than a nuisance; it was a strategic threat. A Serbian victory, or even continued survival as an independent, nationalist power, might inspire the empire’s own Slavic populations to revolt. This would threaten the very survival of the Hapsburg dynasty.

So what better way to eliminate this threat than by using the assassination as a casus belli — a just cause to declare war? Austria-Hungary could portray its attack on Serbia as a necessary move to crush sedition and restore order to the Balkans.

Did Austria-Hungary Also Have Internal Reasons for Its Aggression?

Absolutely. By 1914, the Austro-Hungarian Empire teetered on the brink of collapse. It was a fragile patchwork of ethnicities, languages, and loyalties. The South Slav populations, especially in Bosnia, were restless and repressed.

Interestingly, the Archduke himself might have been a moderating force. Franz Ferdinand supported a vision of a “trialist empire” — a political restructuring that could provide Slavic groups with more representation. Had he lived, he might have eased tensions between Austria-Hungary and Serbia, reducing the push for war.

But fate — or perhaps the conspirators’ fate — denied this alternative path. Certain powerful figures in Vienna, notably Chief of General Staff Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf, had already been pushing for pre-emptive war against Serbia. The assassination ignited their ambitions.

What Was the Bottom Line for Austria-Hungary?

- Remove Serbia as a threat: Crushing Serbia means ending the source of nationalist rebellions that destabilize the empire.

- Stabilize the Balkans: With Serbia neutralized, Austria-Hungary could better control its southern provinces and maintain ethnic order.

- Save the empire: A victory could buy time for the fragile multi-ethnic empire to reform and survive.

In essence, Austria-Hungary seized the assassination as a convenient justification for war. Even if the Serbian government had limited involvement, blaming Serbia fit perfectly with the empire’s strategic goals. The shooter’s nationality was enough to frame the crisis.

Hypothetical: What if Austria-Hungary Didn’t Blame Serbia?

Imagine an alternate universe where Austria-Hungary accepted Gavrilo Princip as a lone wolf with no state backing. Would the empire still march into war? Likely, no. The assassination was just the spark, but pre-existing tensions could have simmered down — or exploded later under different circumstances.

Perhaps Franz Ferdinand’s vision might have opened doors to peace through reform. But Austria-Hungary’s hawks were ready for conflict. So from their perspective, blaming Serbia was pragmatic — a vital step toward aggressive action that was long overdue in their minds.

In Conclusion: The Blame Was as Much About Politics as Proof

Serbia was blamed for the assassination primarily because it served Austria-Hungary’s imperial interests — the assassination provided the perfect excuse to go to war against a hated rival disrupting their regional dominance. This wasn’t just about punishing a criminal; it was about a desperate empire trying to hold itself together.

The bitter irony is that the very man who was killed might have stopped the cycle of violence. The exploding tensions, nationalist fervor, and imperial ambitions all turned a murder into a world war’s starting pistol.

So next time you stumble upon this question — why was Serbia blamed, and what did Austria-Hungary gain — remember: it’s a story of suspicion, opportunity, and empire survival, rather than clear-cut guilt. The assassination wasn’t just a crime; it was a geopolitical game-changer.