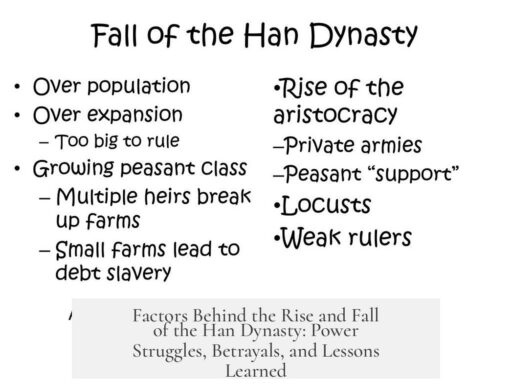

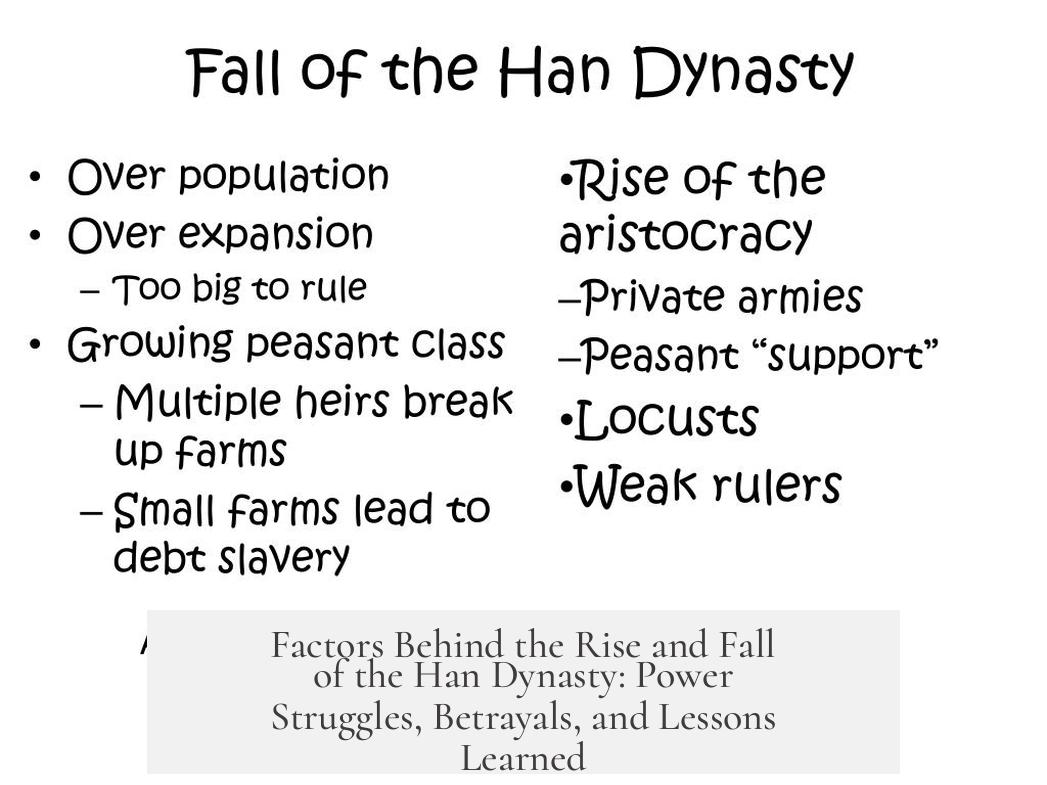

The rise and fall of the Han Dynasty hinge on multiple leading factors rooted in internal power struggles, corruption, military decline, and shifting political alliances, culminating in the dynasty’s collapse in 220 AD.

The immediate causes of the Han Dynasty’s decline focus heavily on the final emperors, particularly Emperors Huan (144-168) and Ling (168-189). Their reigns are marked by favoritism toward eunuchs over the traditional gentry class. This preference weakened governance and instigated resentment among powerful social groups. Although some dispute placing sole blame on these emperors, they undoubtedly contributed to increased corruption.

Eunuchs gained immense influence, often accused of driving the empire toward ruin. Their corrupt activities went unchecked due to inattentive rulers. This era faced ominous signs, including pandemics and a significant uprising known as the Yellow Turban Rebellion in 184. While the rebellion ended within the year, it exposed the fragility of state control. The “Great Proscription” from 169 to 184 saw many gentry members exiled or killed, deepening divisions between factions.

Militarily, the Han Empire was losing grip on its territories. Around Emperor Ling’s death, rebellions shook provinces such as Bing and Liang. Bandits under Zhang Yan controlled parts of the Taihang Mountains, forcing the government to pay bribes to regain stability. This military weakening diminished trust in central authority.

After Emperor Ling, his successor Emperor Bian was a child. The real power rested with the Dowager He clan, who were split in their loyalties. Dowager He and her brother He Miao sided with the eunuchs, while General He Jin, influenced by the gentry, opposed them. This division led to a violent power struggle. He Jin, seeking to remove eunuch influence, was assassinated after a failed plan to eliminate them.

The gentry and military, angered by He Jin’s assassination, launched a brutal crackdown against the eunuchs, killing thousands. This chaos left a power vacuum that Dong Zhuo, a capable but ruthless frontier general, exploited. He seized control of the military forces in the capital, deposed Emperor Bian, and installed Emperor Xian, a younger brother. Dong Zhuo’s rule was marked by tyranny and severe measures aimed at restoring order but lacked legitimacy among the gentry.

Opposition to Dong Zhuo formed quickly. A coalition of military governors, including Yuan Shao, Yuan Shu, and Cao Cao, blockaded the capital, causing severe shortages and inflation. Dong Zhuo eventually fled Luoyang, burning it and relocating the capital to Chang’an. He was assassinated in 192, but the instability continued. Wang Yun’s brief rule was overturned by Dong Zhuo’s former generals, keeping the empire fragmented.

Emperor Xian, though nominally in power, remained a puppet amid this political turmoil. Following infighting among warlords, he fled and was later rescued by Cao Cao. Recognizing the value of imperial legitimacy, Cao Cao controlled Emperor Xian and relocated him to Xuchang. There, Cao Cao centralized power, using the emperor’s authority to legitimize his military and political actions. Emperor Xian’s attempts to regain autonomy failed, and loyalist plots were suppressed.

Upon Cao Cao’s death in 220, his son Cao Pi succeeded him swiftly. Cao Pi compelled Emperor Xian to abdicate, officially ending the Han Dynasty. This marked the start of the Wei kingdom with Cao Pi as its ruler. Meanwhile, Liu Bei, claiming imperial lineage, declared himself emperor of Shu-Han, though it functioned as a separate state and eventually failed against Wei.

| Key Period | Leading Factors | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Emperors Huan & Ling Reigns | Eunuch favoritism, gentry alienation, corruption | Weakened government, rising factionalism |

| Yellow Turban Rebellion (184) | Peasant uprising, military strain | Exposed military weaknesses, social unrest |

| He Jin & Eunuch Conflict | Power struggle, assassination, mass killings | Political chaos, military violence in capital |

| Dong Zhuo’s Rule | Military dictatorship, imperial manipulation | Empire destabilization, coalition resistance |

| Emperor Xian & Cao Cao | Imperial puppet, centralization of power | Transition to Wei, imperial legitimacy exploited |

| Cao Pi’s Usurpation (220) | Formal end of Han, rise of Wei kingdom | End of Han Dynasty’s authority |

- The Han Dynasty’s decline results from a complex mix of internal corruption, military failures, and factional conflicts.

- Favorite eunuchs gained disproportionate power, alienating the gentry and weakening administration.

- Military struggles, including rebellions and banditry, undermined central control.

- The assassination of He Jin and the ensuing violence exposed severe political instability in the capital.

- Dong Zhuo’s seizure of power intensified the dynasty’s fragmentation, provoking coalitions against him.

- Cao Cao’s control of Emperor Xian marked the final phase of Han decline, ending with Cao Pi’s usurpation.

Leading Factors – Rise and Fall of the Han Dynasty: A Tale of Power, Betrayal, and Chaos

If you’ve ever wondered how a mighty empire crafted from ingenuity, strong governance, and cultural brilliance could tumble into chaos and fragmentation, the fall of the Han Dynasty serves as a captivating case study. The leading factors behind the rise and fall of the Han Dynasty weave a dramatic story of imperial weakness, corruption, power struggles, and military strife. Let’s unpack this saga, layer by layer, and explore the lessons locked in its history.

Short-Term Causes: The Emperors and Eunuchs – The Perfect Storm?

First, meet the last two real emperors of the Han, Emperor Huan (reigned 144-168) and Emperor Ling (168-189). Historically, both have received hefty blame for favoring the eunuchs over the gentry. But hold on! Modern historians debate this, so let’s not rush to judgment. What’s undeniable is that this favoritism tilted power in favor of the eunuch faction, with dire consequences.

The eunuchs, those palace insiders often viewed as power-hungry manipulators, are accused of widespread corruption. With the emperors distracted or inattentive, the empire saw its grip slip. Even “signs from heaven” seemed to mock them – a series of pandemics and a massive rebellion known as the Yellow Turban Rebellion erupted in 184.

Although the rebellion was crushed by the end of 184, military weakness showed cracks. Provinces like Bing and Liang slipped out of Han control amid revolts, and bandits like Zhang Yan’s Black Mountain Bandits became major nuisances—bad news for security and order.

The He Clan and Eunuch Faction Fight to the Death

Now, here’s a tangled web of family infighting blended with palace intrigue. Emperor Bian, a child emperor, was more a pawn than a ruler. The powerful He clan, his imperial in-laws, divided their loyalties. Dowager He and her brother He Miao supported the eunuchs, while her other brother, He Jin—the General-in-Chief—was persuaded by the gentry to wipe out the eunuch threat.

Hope didn’t last long for eunuchs. They withdrew temporarily in a bid to save their skins, but the ever-tense atmosphere led He Jin to demand their execution. Sadly, this plan blew up in his face when some secret leaked, possibly thanks to Yuan Shao’s overreach in arresting families. The eunuchs made a comeback and struck a lethal blow by assassinating He Jin in 189 while he returned from seeing his sister.

With He Jin dead, the gentry feared fierce retaliation. Soldiers, who liked He Jin, were enraged. Without strong imperial backing, chaos erupted. Brutal fighting happened when troops stormed the palace. Survivors without beards cleverly revealed their faces to avoid mistaken identity as eunuchs. Thousands perished — a grim turning point illustrating how fragile imperial unity had become.

Dong Zhuo: From Frontier General to Tyrant

Ever heard of a “bad decision” that changed everything? Calling in Dong Zhuo was just that. He Jin had sought military reinforcement amid chaos, but Dong Zhuo was known for his rebellious streak. Once in power, he didn’t waste time. Taking advantage of the power vacuum and political infighting, Dong Zhuo seized control with his armed forces.

This rough-handed warlord had little political savvy or respect from the gentry. He deposed weak Emperor Bian and installed the younger Emperor Xian, then forced Dowager He to abdicate and famously killed her just a day later. His rule was marked by strict, often brutal, attempts to restore order—but at great cost.

Meanwhile, a coalition formed to oppose Dong Zhuo. Key players like Yuan Shao, Yuan Shu, and Cao Cao raised armies and blockaded the imperial court. Rising food prices and inflation added fuel to the fire, making life miserable for commoners while battles raged. Dong Zhuo eventually abandoned the capital Luoyang, retreating to Chang’an, torching Luoyang to the ground in a scorched earth move.

From Assassination to Puppet Rule: Emperor Xian’s Struggle

In an unexpected twist, Dong Zhuo was assassinated by minister Wang Yun and bodyguard Lu Bu in 192. But peace didn’t follow. Wang Yun’s high-handed ruling style drove Dong Zhuo’s generals, like Li Jue, into rebellion. The political landscape remained fractured, and true power was elusive.

Emperor Xian, now adult, was little more than a figurehead. He escaped the capital in 195, dodging hostile generals, and managed to return to Luoyang’s ruins after a desperate journey. Support was thin, and rival factions constantly vied for control over him.

Cao Cao, the governor of Yan, entered the picture here. Unlike others, he answered Emperor Xian’s call for help, gradually taking military charge and escorting the emperor to his power base in Xuchang. Cao Cao brilliantly used imperial legitimacy as a political tool, granting ranks and favor to secure loyalty.

However, Emperor Xian’s captivity was fraught. Loyalists and discontent generals launched failed plots to free him. Tragically, even Empress Fu, his pregnant wife, was killed amid the turmoil. The Han emperor was a gilded cage monarch—real power rested elsewhere.

The Final Nail: Cao Pi and the End of Han

Cao Cao died in March 220. Having conquered about two-thirds of the land, he left a legacy of military might and central control. His son Cao Pi quickly stepped in, solidifying control and smoothing the political landscape.

In December of the same year, Emperor Xian abdicated, marking the official end of the Han Dynasty. It was the close of an era spanning over four centuries—full of cultural brilliance but ultimately undone by political fragmentation and power grabs.

Not everyone accepted this end. Liu Bei, a rival warlord with some imperial bloodline, claimed the Han throne, calling his kingdom Shu-Han. But with his death and Shu’s eventual surrender in 263, historians generally agree the Han Dynasty had truly concluded.

What Lessons Does the Collapse Teach Us?

The rise and fall of the Han Dynasty teach us much about power’s fleeting nature and the dangers of corruption. Mid-level factions—the eunuchs and gentry—played outsized roles in accelerating the collapse. Military strength didn’t guarantee stability; internal strife dealt fatal wounds.

Would a stronger emperor or more united ruling class have prevented the collapse? Possibly. Yet the Han story highlights how systemic weaknesses and shortsighted decisions snowball into ruin.

It also invites a question: How do modern states avoid the pitfalls of factionalism and corruption? Can centralized power coexist with broad accountability? These questions remain relevant 2,000 years after the fall of Han.

Summing Up the Han Dynasty’s Climactic End

To wrap it up succinctly:

- Internal corruption by eunuchs undermined governance.

- Military weakness and local uprisings eroded control.

- Family factionalism splintered political unity.

- Power grabs by generals like Dong Zhuo led to rebellion and destruction.

- Puppet emperors masked the reality of military rule.

- Final usurpation by Cao Pi ended the dynasty’s ancient reign.

The Han Dynasty’s fall is not just history; it’s a vivid reminder of how leadership, legitimacy, and loyalty shape the destiny of empires. Its story remains a compelling lens through which to view leadership challenges, political dynamics, and the persistent human drama of power.

What role did eunuchs play in the fall of the Han Dynasty?

Eunuchs held great power during the reigns of Emperors Huan and Ling. They were accused of corruption and manipulating the court, which weakened the government and led to conflicts with the gentry and military decline.

How did He Jin’s assassination impact the power struggle in the Han court?

He Jin’s murder sparked violent clashes between the eunuchs and gentry factions. His death removed a key figure trying to control the eunuchs, leading to chaos and the rise of warlords like Dong Zhuo.

Why was Dong Zhuo able to seize control of the Han government?

Dong Zhuo used his troops to dominate the capital after He Jin’s death. With the gentry weakened by internal strife, Dong Zhuo imposed his rule through military force despite lacking political support.

How did Cao Cao use Emperor Xian’s status to strengthen his power?

Cao Cao protected Emperor Xian and relocated him to Xuchang. Using the emperor’s legitimacy, he appointed officials and gained political influence, effectively controlling the Han government.

What marked the official end of the Han Dynasty?

After Cao Cao’s death, his son Cao Pi forced Emperor Xian to abdicate in 220. This act officially ended the Han Dynasty and led to the rise of the Wei kingdom under Cao Pi’s rule.