Thomas Edison did not originally invent the phonograph but improved it through experimentation and material innovation. While many inventors worked on sound recording devices before Edison appeared, he focused on refining the technology, particularly by testing different cylinder coatings until finding one that worked effectively.

Before Edison’s phonograph, researchers explored sound recording principles but struggled with practical materials. Edison’s approach involved trial-and-error with random substances to develop a better-recording surface. This practical tinkering brought the phonograph closer to market viability.

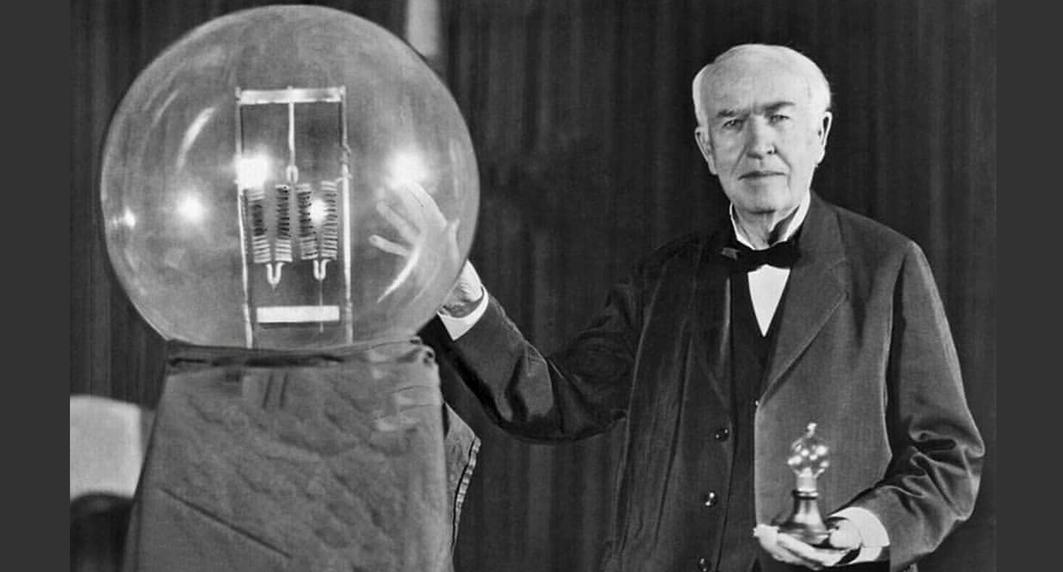

This strategy fits Edison’s typical method. He often engaged with emerging inventions that were incomplete or imperfect. Rather than creating entirely new concepts, Edison iterated on existing ideas to create functional products. This pattern applies to other inventions like the light bulb, where his main contribution lay in discovering a suitable filament material.

Edison’s talent extended beyond invention. He understood U.S. patent laws and used this knowledge to secure patents for improvements, strengthening his commercial position. He also maintained relationships with skilled scientists, which enhanced his scientific understanding above the average inventor. His business acumen turned innovations into profitable enterprises, frequently overshadowing original inventors who struggled financially.

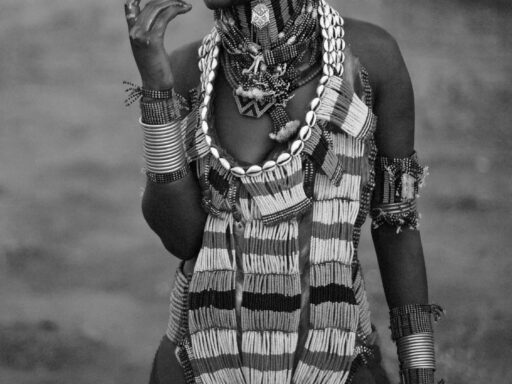

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Original idea | Not Edison’s; phonograph concepts existed previously |

| Edison’s contribution | Experimental refinement of materials for working phonograph |

| Innovation method | Trial-and-error tinkering on imperfect inventions |

| Business strategy | Strong patent use and commercialization skills |

While Edison did not directly steal invention ideas, his role was primarily that of an innovator refining existing concepts and using legal and business tools to claim invention credit and commercial success. This nuanced role explains why some view him as overshadowing original ideators rather than outright theft.

- Edison improved but did not originate the phonograph concept.

- Used trial-and-error with materials to make the phonograph practical.

- Typical approach: refine existing inventions rather than invent from scratch.

- Combined technical skills with patent law knowledge to maximize profit.

- Often eclipsed original inventors through business and legal expertise.

Did Edison Steal the Phonograph Idea? The Truth Behind the Inventor’s Reputation

Was Thomas Edison a thief when it came to the phonograph invention? The short, nuanced answer is: No, but the story involves more than mere invention. Edison’s talent wasn’t always groundbreaking ideas alone. He excelled at refining and making inventions practical, often standing on the shoulders of earlier discoveries.

If you think Edison outright stole the phonograph idea, you might be echoing a popular—and partially true—reputation. Edison is known for taking ideas from others, improving upon them, and using his mastery of patent law and business to dominate markets. But was this the case specifically with the phonograph? Let’s unravel the tale.

The Phonograph: A Curious Case of Innovation and Refinement

The phonograph, Edison’s famous audio recording device, wasn’t born out of thin air. People were exploring sound recording in various forms before Edison’s 1877 breakthrough. However, what Edison brought to the table was a critical leap in making the idea workable and reproducible.

In the 19th century, inventors dabbled with capturing sound vibrations, but none created a practical machine. Their efforts often stalled due to technical challenges, especially in materials—how to record sound on a medium that could be played back reliably.

Edison’s genius lay not in originating the concept but in overcoming the major hurdle of materials. He tested an array of coatings on a cylinder until he found one that successfully recorded sound. This trial-and-error, material-driven approach typifies Edison’s inventive style.

The Tinkerer’s Edge: How Edison Worked with Ideas

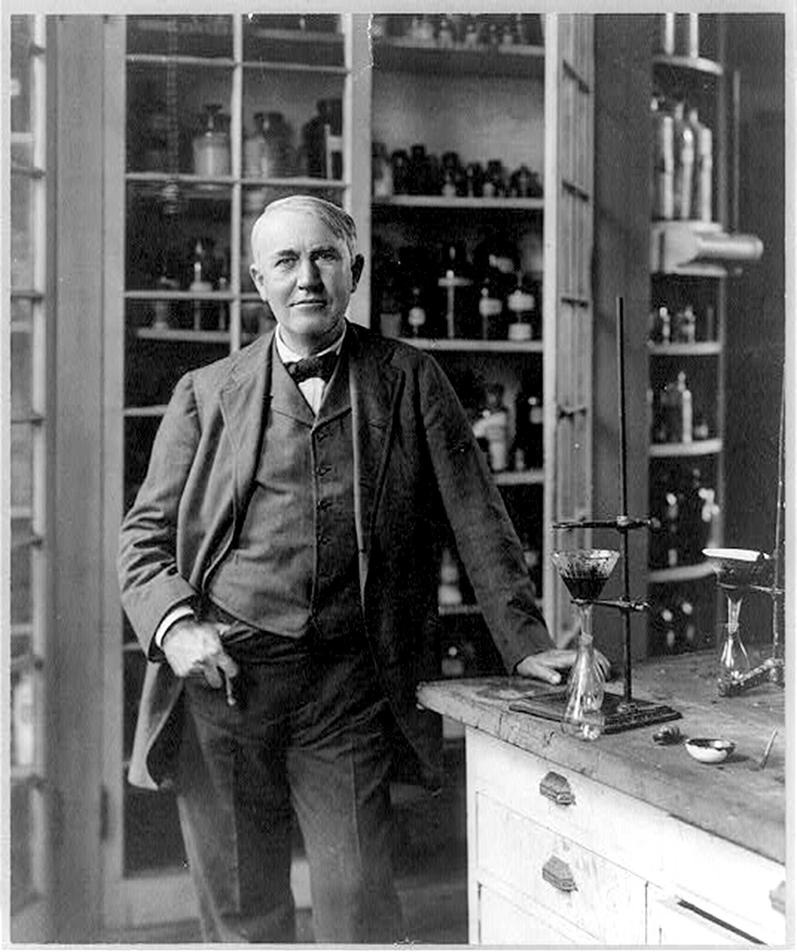

Edison is often described as “a tinkerer.” Unlike pure theoreticians, he preferred hands-on experimentation. Rather than being a solo scientific genius, he had an experimental workshop. Here, Edison and his team conducted countless trials on filaments for the light bulb and coatings for the phonograph cylinder.

This hands-on, trial-and-error process sometimes looks like borrowing—not stealing. Edison didn’t invent from scratch; he capitalized on imperfect ideas already floating around. His knack? Making these ideas practical and profitable.

Was This “Stealing” or Smart Play?

It’s tempting to label Edison a crook based on his reputation. He understood U.S. patent law better than most. Edison knew how to use it to secure patents, often filing broad claims or just the right improvements over existing inventions. This gave him leverage to build empires while many original inventors struggled financially.

Think of it this way: Edison knew the system inside out. He exploited imperfections in emerging inventions, then ran with them. People who came before Edison often lacked the resources or savvy to make their work commercially viable.

So, while he didn’t invent the phonograph idea fresh, Edison’s improvements transformed it from a vague concept into a workable device. His financial acumen ensured he got the credit, fame, and fortune.

Contacts and Knowledge: The Edison Advantage

Edison wasn’t just guessing blindly. His network of contacts included well-established scientists. This peer access empowered him with scientific knowledge beyond average understanding.

While Edison’s methods sometimes irked purists, his ability to mix practical experimentation with savvy was unmatched. His success was as much about business smarts as it was about innovation.

A Modern Perspective: What Can We Learn?

The Edison-phonograph saga invites a larger question: What defines invention? Is it the original idea, the practical refinement, or the ability to bring a product to market?

Edison’s story underscores this complexity. He wasn’t the lone genius inventing in solitude. He was more like a seasoned chef blending known ingredients into a new recipe that customers love.

For today’s inventors and entrepreneurs, the lesson is clear. First, understanding the groundwork laid by others is crucial. Second, relentless experimentation and an eye for materials are game changers. Third, mastering the business and legal playground is vital to lasting success.

In other words, sometimes improving a bumpy road matters more than inventing a new highway.

Practical Tips Inspired by Edison’s Approach

- Test and iterate. Don’t hesitate to try multiple materials or methods in your invention process. Edison’s success shows how persistence pays off.

- Know your market. Make inventions practical and user-friendly. A brilliant concept is only half the battle.

- Study patent law. Protect your ideas but also understand the competitive landscape. Smart filing can save you headaches.

- Build a network. Don’t work in isolation. Collaborate and learn from experts—a gap in knowledge can stall progress.

The Bottom Line

Edison’s phonograph success wasn’t stolen innovation but an inspired iteration. His genius lay in spotting weak inventions, experimenting relentlessly with materials, and securing patents and profits. While some may brand him a ‘thief,’ the truth reflects a complex mix of innovation, hands-on trial, legal savvy, and market instincts.

Like any historical figure, Edison is a blend of admirable traits and controversial tactics. So next time you hear he stole ideas, remember: He was less a thief and more a relentless tinkerer, and that made all the difference.