Saladin (Salahuddin Ayyubi) was never truly forgotten in the Muslim world before the colonial era, contrary to a popular narrative that credits European colonialism for reviving his memory as a prominent anti-Western figure.

This widespread but simplistic claim suggests that Muslim societies largely forgot the Crusades and their key figures until renewed 19th-century encounters with European powers. According to this view, Saladin’s renown in the Muslim imagination had faded, while other Muslim leaders like Nur al-Din and Baybars retained prominence. Nur al-Din was revered by religious scholars as an exemplary mujahid, and Baybars became a folk hero through a famous epic poem performed publicly, even into the 19th century. Saladin, however, was supposedly sidelined because his victory over the Crusaders was incomplete—he recaptured Jerusalem but did not expel the Crusaders fully, a feat Baybars ultimately achieved in 1291. His Kurdish ethnicity also allegedly reduced his appeal in the Ottoman and Arab nationalist frameworks, which favored Turkic and Arab heroes like Baybars.

European prestige around Saladin notably influenced Ottoman awareness. European leaders, such as Kaiser Wilhelm II, visited and admired Saladin’s tomb in Damascus, prompting the Ottomans to build a more ornate mausoleum in 1898. Wilhelm II’s pilgrimage to Jerusalem dressed as a Crusader brought attention to Saladin’s role in resisting Western Crusaders. Facing European colonial threats, the Ottoman regime leveraged Saladin’s symbolic resistance to Western powers, increasing his prominence as a unifying Muslim hero in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

However, modern scholarship, including the work of Abouali, challenges the premise that Saladin had fallen into obscurity before this period. Historical and literary sources from the Mamluk and Ottoman eras repeatedly mention Saladin. His figure is present not only in scholarly circles but also in popular Muslim memory. This continuous presence contradicts the narrative that Europeans “rediscovered” Saladin for the Muslim world.

The fame of Baybars, partly fueled by his epic poem, was highly visible and attracted European attention, perhaps leading Western observers to mistakenly assume Saladin’s obscurity based on surface-level cultural markers. While Baybars was a folk hero through oral tradition, the broader historical record contains sustained recognition of Saladin across centuries.

The idea that the European West “re-introduced” Saladin to Muslims is deeply tied to Eurocentric and orientalist assumptions. It presumes Muslim forgetfulness and imposes Western perspectives of heroism upon Muslim history. Such views dismiss the possibility that Muslim societies had nuanced and legitimate ways of remembering and valuing their historical figures, different from European conceptions. There is no inherent need to “correct” an alleged Muslim neglect of Saladin since Muslim memory has never been monolithic or measured by European standards.

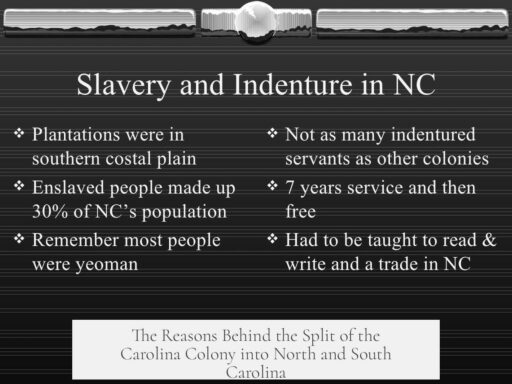

| Aspect | Common Narrative | Revised Scholarly View |

|---|---|---|

| Saladin’s Status Pre-Colonialism | Forgotten or marginal | Continuously remembered in texts and popular memory |

| Prominence of Other Figures | Nur al-Din and Baybars overshadow Saladin | All three figures recognized but in different ways |

| Role of European Interest | European admiration revived Saladin’s memory | European interest amplified Ottoman political use but did not create fame |

| Ethnic & Political Factors | Saladin’s Kurdish identity diminished his Muslim appeal | Ethnic factors influenced narratives but did not erase his legacy |

In summary, Saladin’s memory was never erased or dormant. It evolved alongside other historical figures and was embedded in Muslim historical consciousness. European colonial interest highlighted and reshaped his symbolic usefulness but did not create his significance from nothing. Modern research reveals a complex and continuous Muslim engagement with Saladin’s legacy beyond simplistic colonial-era reinterpretations.

- Saladin was consistently mentioned in Mamluk and Ottoman histories and literature.

- Popular memory preserved Saladin alongside Baybars and Nur al-Din.

- European admiration in the 19th century increased Ottoman political use of Saladin as a symbol.

- The idea of Muslim forgetting reflects Eurocentric assumptions and incomplete Western knowledge.

- Diverse Muslim communities maintained nuanced views of Saladin’s historical role.

Was Saladin Forgotten in the Muslim World Before Colonialism? Debunking a Common Myth

Is it true that Salahuddin Ayyubi (Saladin) was not well-known in the Muslim world before colonialism pushed him as a strong anti-Western figure? The short answer is: no, Saladin was not forgotten, nor was his memory absent among Muslims before colonial times. But let’s peel back the layers of this popular narrative, and see what history and scholarship really say.

This question matters because it touches on how history is remembered, reshaped, and sometimes distorted by power, politics, and identity. So buckle up – we’re diving into facts, myths, and a dash of European political theater.

The Popular Story: Saladin as a Rediscovered Hero

It’s often claimed that Muslims largely forgot the Crusades, and by extension Saladin, until the 19th century. According to this view, the Jihadic zeal of figures like Nur al-Din and the legendary exploits of Baybars eclipsed Saladin’s memory. The narrative goes that Baybars, who finally expelled the Crusaders in 1291, was the true hero in Muslim eyes. Meanwhile, Saladin, despite his stunning victory in retaking Jerusalem during the Third Crusade, didn’t quite finish the job, so his legacy was diminished.

Ethnic politics supposedly played a role here too. Saladin was Kurdish, whereas Baybars was Turkic. Since the Ottomans — proud Turkic rulers — dominated the Muslim world for centuries, scholars argue they favored Baybars as a symbol. Moreover, the story is often told that Saladin’s popularity surged only after the West “discovered” him. European leaders like Kaiser Wilhelm II openly admired Saladin and even *redecorated* his tomb to impress visiting dignitaries, notably in 1898.

In the eyes of some Western scholars of the 19th and early 20th centuries, Saladin was little more than a European construction — a hero resurrected to serve newly emerging anti-Western colonial sentiments in the Muslim world.

Wait, But… Saladin Was Actually Remembered All Along

This neat narrative crumbles under close examination of primary sources and historical context. Thankfully, serious modern scholarship reveals a more complex picture. Far from being a forgotten figure, Saladin’s name and deeds appeared regularly in Mamluk and Ottoman historical works. These texts, not only in scholarly circles but also in popular culture, remembered Saladin vividly.

For example, Arab Muslim popular memory prominently featured Saladin alongside other medieval heroes. While Baybars enjoyed a *well-known epic poem* that fueled his fame at public performances, Saladin’s memory was alive in the written histories and popular storytelling that traveled through the centuries. Europeans tend to highlight visible folk culture like Baybars’ epic to gauge popular memory. But this misses the rich and layered Muslim historical tradition where Saladin was celebrated and respected.

Abouali, a notable modern historian, firmly challenges the “forgotten Saladin” narrative. He presents substantial evidence that Muslims continuously acknowledged Saladin’s achievements. From the Mamluk to Ottoman times, Saladin’s legacy was part of the cultural fabric, not an empty museum piece.

The Tomb Story and European Influence on Ottoman Memory

Yes, European attention to Saladin happened. It’s true Europeans often visit historic tombs for hero worship or political symbolism. Wilhelm II’s 1898 pilgrimage to Saladin’s tomb in Damascus — and his theatrical crusader costume trip to Jerusalem — is a famous episode. It’s no secret that the Ottomans upgraded Saladin’s shrine to impress these European visitors.

But this European spotlight didn’t “create” Saladin’s reputation in Muslim lands. Instead, it highlighted pre-existing reverence that the Ottomans leveraged as symbolic resistance against encroaching colonial powers. Riding the wave of European admiration for Saladin, the Ottomans promoted him as a figure representing defiance against Western imperialism.

This angle is compelling. Here, Saladin became a rallying figure — a symbol of unity and resistance — framed by a context of 19th-century colonial pressure. Still, this does not equate to him being unknown or forgotten before then. The colonial context simply amplified an existing legacy.

Why Might the “Forgotten Saladin” Story Have Gained Traction?

- Eurocentric bias: Many early Western historians and Orientalists assumed their perspective was the default truth. Because Europeans admired Saladin, they concluded Muslims must have neglected him — implying a need to “set the record straight.” This paternalistic view misses the point that Muslim memory systems simply valued their heroes differently.

- Visible popular culture vs literary memory: Baybars’ epic was performed publicly and repeatedly, a conspicuous symbol of folklore. Saladin’s remembrance was often more textual and scholarly, or embedded in subtle forms of storytelling less obvious to European observers.

- Ethnic and political identity: Ottoman and later Arab nationalist rulers emphasized heroes aligning with their own ethnic or political identities. Still, this selective emphasis doesn’t erase broader historical remembrance.

Ask yourself: Why should a society value one historical figure over another? Does Western admiration dictate what matters to Muslim communities? Quite the opposite — Muslim historical imagination is rich and multifaceted, valuing heroes like Saladin, Nur al-Din, and Baybars according to complex cultural and political factors.

Lessons from This Historical Debate

This discussion shows how important it is to question popular historical narratives, especially those shaped by colonial or Eurocentric perspectives. The story of Saladin’s remembrance illustrates how history can be oversimplified to serve contemporary agendas.

- Historical memory is never uniform. Heroes’ reputations rise and fall based on context, politics, and cultural preferences. Saladin was a hero, but not the only one or necessarily the most prominent at all times.

- Western narratives don’t always capture the full truth. Simplifying Muslim history into “forgotten” or “rediscovered” categories does a disservice to the richness of Islamic cultural heritage.

- Saladin’s legacy is a shared one. He belongs not only to Muslim history but to global history. His fame in Europe sparked Ottoman revalorization but did not create his memory out of thin air.

Practical Takeaway: A Balanced Understanding of Saladin’s Legacy

If you’re reading about Saladin, be cautious about sweeping claims that Muslims forgot him until colonial times. Instead, recognize that his memory never died out but evolved. Scholars today urge nuance: honor Saladin’s role without dismissing the prominence of other heroes like Baybars or Nur al-Din.

For anyone interested in Muslim history, this reminds us: dig deeper than surface narratives. History is messy. Heroes mean different things to different communities at different times. And sometimes it takes a European emperor in a crusader costume to remind the Ottomans about a hero they already cherished!

Final Thought

Next time you hear the claim: “Saladin was unknown in the Muslim world before colonialism,” smile knowingly. You’re now armed with facts. He was there all along — remembered in texts, stories, and hearts. Colonialism didn’t introduce Saladin; it highlighted a hero who had long been part of Muslim historical consciousness.