Constantine the Great is not officially considered a saint by the Roman Catholic Church. While his mother, Saint Helena, holds recognized sainthood in Catholicism, Constantine himself has not been canonized by the Church. This distinction shapes how Constantine’s legacy is viewed within Catholic tradition compared to Orthodox Christianity.

The Eastern Orthodox Church venerates Constantine as a saint, acknowledging his role in shaping early Christianity through the Edict of Milan and his patronage of many Christian institutions. This veneration contrasts with the Catholic Church’s more reserved stance, where Saint Helena is honored distinctly for her pious contributions and relic discovery.

The Italian poet Dante Alighieri offers a complex perspective on Constantine in his Divine Comedy. Dante places Constantine in Paradise (Canto XX) among the “just princes” such as King David and Emperor Trajan. This placement suggests respect for Constantine’s rulership and contributions. However, Dante’s writings also display tension regarding Constantine, especially in relation to the “Donation of Constantine.”

The Donation of Constantine, purportedly a decree transferring authority over the Western Roman Empire to the Pope, was historically accepted during Dante’s time. Yet Dante opposed this claim, highlighting the contradiction between Constantine’s sanctity and the political power the donation implied. Modern scholarship, thanks to Lorenzo Valla in the 15th century, has established that the Donation was a forgery from the 9th century, invalidating its legitimacy entirely. Dante, living before this discovery, regarded the document as authentic but resisted its implications.

| Aspect | Detail |

|---|---|

| Roman Catholic Church | No official sainthood for Constantine |

| Eastern Orthodox Church | Recognizes Constantine as a saint |

| Saint Helena | Recognized as a saint by Roman Catholics |

| Dante’s View | Places Constantine in Paradise but critical of Donation of Constantine |

The key takeaways:

- Constantine is not canonized by the Roman Catholic Church.

- Eastern Orthodox Church venerates Constantine as a saint.

- Dante honors Constantine spiritually but opposes the Donation of Constantine.

- Saint Helena, Constantine’s mother, is recognized officially in Catholicism.

- The Donation of Constantine is a known medieval forgery, disproven after Dante’s time.

Is Constantine the Great Considered a Saint by Roman Catholics?

Simply put, Constantine the Great is not officially recognized as a saint by the Roman Catholic Church today. This may surprise some, since he’s one of the most influential emperors in Christian history. But the story is a bit more nuanced than just a yes or no.

Constantine’s legacy looms large, but when it comes to canonization by the Roman Catholic Church, he isn’t on that list. Yet, his mother, Helena, holds sainthood in high regard within the Catholic Church. How did this difference come about? And why does the Orthodox Church view Constantine differently? Strap in—it’s a historical ride with a dash of intrigue, theology, and even some literary drama.

Constantine’s Status in the Roman Catholic Church: Officially Not a Saint

The Roman Catholic Church has a formal procedure for declaring someone a saint. It requires evidence of miracles and a virtuous life led in line with Christian teachings. Despite Constantine’s monumental role in legitimizing Christianity within the Roman Empire with the Edict of Milan (313 AD), the Church never officially canonized him. No feast day, no universal veneration, no entry in the Roman Martyrology. This means that, from the Catholic perspective, Constantine remains a historical figure but not a sanctified one.

So, what exactly holds him back? It’s partly due to his complicated political and religious actions as emperor. For example, Constantine’s life is full of power struggles, wars, and political maneuvers. His conversion to Christianity was perhaps gradual and intertwined with political motives. Roman Catholics tend to reserve sainthood for those whose holiness and faith life are beyond reproach, and Constantine’s historic complexity clouds that image.

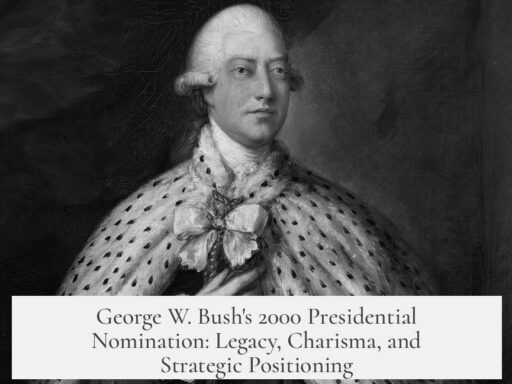

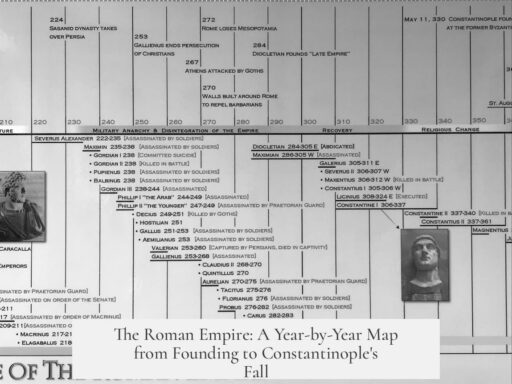

Eastern Orthodox Church: Constantine the Saintly Emperor

Meanwhile, on the other side of Christianity, the Eastern Orthodox Church holds a different view. The Orthodox venerate Constantine as a saint. He’s often called “Constantine the Great, Equal-to-the-Apostles,” reflecting his pivotal role in establishing Christian dominance across the Roman Empire. Alongside his mother Helena, revered for finding the True Cross, Constantine is celebrated for his part in shaping Christian civilization.

This veneration differs from Western practice largely due to varying historical and theological traditions. In the East, Constantine’s role in convening the First Council of Nicaea (325 AD), which settled critical Christological debates, elevates him as a defender of orthodoxy. His political and spiritual impact makes sanctity a fitting title there.

Dante’s Ambiguous Take: A Literary Glimpse at Constantine’s Afterlife

Fast forward to medieval Italy—Dante Alighieri wrestles with Constantine’s legacy in his Divine Comedy. Fascinatingly, Dante doesn’t cast Constantine into Hell. Instead, he places him in Paradise, among the “just princes” like King David and Hezekiah. This honor hints at Dante’s recognition of Constantine’s contribution to Christianity and good governance.

Yet, Dante’s view isn’t free of tension. He explicitly criticizes the “Donation of Constantine,” a document claiming that Constantine granted the Pope vast secular powers. Dante sees this document as problematic, even while believing it authentic. The donation’s dubious legitimacy troubles Dante, reflecting broader debates about Church and state authority during his era.

To put it bluntly, Dante seems torn: admiring Constantine’s saintly qualities but doubting the political legacy tied to the Donation. This paradox adds an intriguing cultural and historical layer to how Constantine’s memory endured in Western thought.

The Donation of Constantine: Forgery and Historical Reckoning

Speaking of the “Donation,” here’s where history blows a whistle. The so-called Donation of Constantine, which supposedly granted the Papacy temporal authority over the Western Roman Empire, has been proven a forgery. Lorenzo Valla, a Renaissance scholar, exposed its falsehood in the 15th century. His textual analysis revealed that the document was manufactured, likely in the 9th century, well after Constantine’s time.

Dante, writing in the 13th-14th century, had no access to Valla’s findings and had to rely on the widespread belief in the Donation’s authenticity. This meant engaging with a politically loaded myth that shaped medieval Church-State relations. Dante’s ambivalence about the Donation mirrors a broader skepticism about mixing religion and politics—a debate still relevant today.

What Does This All Mean for Us?

So, is Constantine a saint in the eyes of the Roman Catholic Church? No official stamp guarantees that. But his impact on Christianity cannot be overstated. For those curious about religious history, this distinction opens up fascinating discussions about how sainthood is granted, how different Christian traditions remember influential figures, and how history intertwines with theology and politics.

And here’s a fun question to ponder: If Dante were around today, having access to Valla’s research, would his portrayal of Constantine change? Would Constantine still reside in Paradise among the just princes or face a complex re-evaluation? Literary allusions aside, it shows how historical interpretation evolves with new truths.

Practical Tip for History Buffs and Faith Seekers

- If you want to understand sainthood deeply, look at the formal canonization process used by the Catholic Church and compare with the Eastern Orthodox veneration practices.

- Explore primary texts like Dante’s Divine Comedy to see how medieval minds grappled with these ambiguities.

- Consider how political power and religious authority have mingled across history—in Constantine’s era and beyond.

Studying Constantine through these lenses enriches your grasp of Christian heritage, showing that sainthood is more than wearing a halo. It’s a complex dance of faith, history, and human imperfection.

In Conclusion

Constantine the Great isn’t a Roman Catholic saint in any formal sense. He is, however, recognized as a saint by the Orthodox Church. His mother, Helena, enjoys Catholic sainthood. Literary giants like Dante recognized Constantine’s greatness but wrestled with his political legacy, especially the Donation of Constantine. This story blends history, faith, and scholarship—a reminder that sainthood reflects more than a life well-lived: it’s a dialogue between human deeds, spiritual ideals, and evolving interpretation.