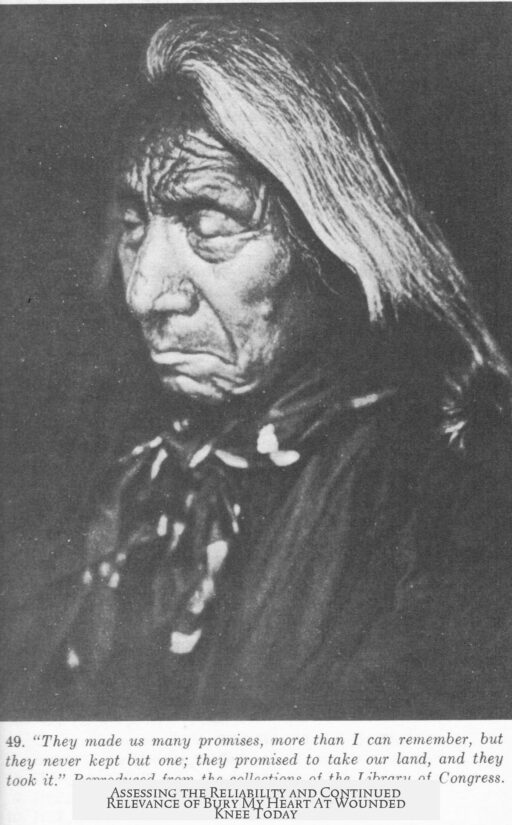

Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee by Dee Brown is a historically significant book that remains a valuable source today despite some limitations in accuracy and scope. Published in 1970, it provides a Native American-centered perspective on the history of the American West. This was groundbreaking for its time, challenging decades of narratives that favored settlers and the U.S. Army as heroes. Brown used both Native and white sources to tell the stories of Native American tribes facing broken treaties, massacres, and brutal policies.

The book’s greatest strength lies in its exposure of harsh realities. It documents the repeated betrayal of Native Americans by the U.S. government. Brown does not shy away from describing massacres such as the Sand Creek Massacre. Notably, archaeological research in the late 1990s has largely confirmed Brown’s depiction of this event, lending credibility to his account.

Brown presents a nuanced narrative rather than a simplistic “white man bad, Indian good” story. He acknowledges that some white individuals held diverse opinions and behaved differently toward Native tribes. The book illustrates that both Native Americans and whites made complex decisions, sometimes aligning with or opposing one another. This layered view contrasts with Hollywood portrayals prevalent before 1970.

However, some criticisms exist. Brown occasionally portrays Native tribes as more passive than they were in reality. The book sometimes downplays Native agency in treaty violations or conflicts. In addition, Brown ends the narrative abruptly at the 1890 Wounded Knee Massacre. This can mislead readers into thinking Native American struggles ended there, whereas violence and resistance continued well into the 20th century.

Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee also overrelies on certain stereotypes, notably the Noble Savage trope. It tends to emphasize the loss of Native culture but gives less attention to the resilience and ongoing cultural revitalization among Native peoples. The portrayal of Native Americans largely as victims may flatten their complex identities and experiences. More ambiguity about Native leaders’ motivations and responses to U.S. policies would have strengthened the account.

Moreover, Brown’s goal was to present a clearly Native-centered story rather than a perfectly balanced or strictly accurate one. This makes the book powerful but means readers should consult other sources for a fuller picture. Some inaccuracies stem from limited access to sources in Brown’s time, nearly 55 years ago.

Despite these drawbacks, the book still resets the dominant narrative of the American West. It offers a necessary correction to traditional histories that ignored Native voices. Brown’s work inspired subsequent authors and scholars to explore Indigenous perspectives more deeply. Readers interested in Native American history and U.S. policy toward tribes will find Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee a compelling introduction.

| Aspect | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Perspective | Native American-focused narrative; challenges mainstream accounts | Sometimes oversimplifies Native actions and motivations |

| Historical accuracy | Archaeological findings support key events like Sand Creek Massacre | Some inaccuracies due to source limitations; narrative impact prioritized over balance |

| Narrative style | Accessible, engaging storytelling; nuanced portrayal of characters | Relies on noble savage trope; largely victim-focused depiction |

| Scope | Covers broken treaties, massacres, policies up to 1890 | Ends abruptly at Wounded Knee, omitting 20th century struggles |

For those seeking further insight, books such as Patricia Nelson’s Legacy of Conquest and Thomas King’s The Inconvenient Indian complement Brown’s work with updated perspectives and broader contexts. Helen Hunt Jackson’s 1881 A Century of Dishonor inspired Brown and remains a foundational historical text.

The 2007 HBO adaptation of Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee offers a visual and dramatic interpretation. It highlights assimilation policies and the ongoing Native American struggle, serving as a useful companion to the book.

- Brown’s book is historically important and influential, valuable for understanding Native American experiences.

- It challenges traditional Western narratives but should be read alongside other sources.

- Some portrayals simplify Native agency and end the story too soon.

- The book’s focus on Native perspectives provides necessary balance to earlier histories.

- Further reading and modern research expand and update Brown’s account.

Is Bury My Heart At Wounded Knee a Reliable Source, and Worth Reading Today?

Yes, Bury My Heart At Wounded Knee is a valuable, though imperfect, source that offers an essential Native-centered perspective on American history. It challenges traditional narratives and remains worth reading today for its powerful storytelling and groundbreaking viewpoint.

Let’s dive into why this 1970 classic has earned its place on many reading lists—while still understanding its limitations.

A Fresh Lens on American History

When Dee Brown dropped this book in 1970, it was like flipping history on its head. The story of the American West had long been told from the cowboys’ and settlers’ viewpoint. You know, the usual “good guys in hats” saga. Brown dared to take the Native-first perspective—even though he himself was white.

He wove together Native voices, white reports, and a range of accounts that disrupted decades of glorified Western narratives. Readers first encountered stories from the viewpoints of tribes who often suffered silently in the shadows of popular history.

This was not just rewriting history; it was more about showing the other side that had been shoved aside. So, if your knowledge of the American West feels a bit one-dimensional, Brown’s book offers a much-needed jolt to your historical compass.

Strengths That Pack a Punch

The book dives unflinchingly into the brutal realities faced by Native tribes. Broken treaties, massacres, betrayals—all laid out in clear, direct prose. Brown doesn’t sugarcoat the U.S. government or army’s actions; he shows the harsh truths.

What’s more, he adds nuance. Key figures—whether military leaders or tribal chiefs—are portrayed with complexity rather than as mere heroes or villains. This shades history with the grey tones of real human decisions, underscoring that right and wrong were never that simple.

Take the depiction of the Sand Creek massacre. Decades after the book’s release, archaeological digs in the 1990s confirmed Brown’s recounting. That’s a little research backup that boosts the book’s historical credibility in some key areas.

Still wondering whether it’s too biased? Brown’s narrative is not about making every white figure look bad or every Native character saintly. It shows diversity of thought among settlers and army officials about how to deal with Native tribes. So, it breaks away from the “all white man bad” trope and invites readers to wrestle with real-world complexities.

Where the Book Trips Up

No masterpiece is without flaws. It’s important to spot a few of Brown’s stumbles to align expectations.

- First, some critics point out that the tribes come off as a bit too passive at times. The narrative sometimes glosses over Native agency or implies they trusted the Army more than they might realistically have. This flattens the powerful, active roles tribes played in their own stories.

- The book ends with the tragic Wounded Knee massacre in 1890. But here’s the catch: it leaves you feeling like history just stopped there. In reality, Native struggles for rights, recognition, and survival didn’t end but continued into the 20th century and beyond.

- Another criticism hits the “Noble Savage” trope. Brown sometimes paints Native culture as vanishing, which risks romanticizing Indigenous peoples rather than showing their resilience and cultural revival efforts happening today.

- Brown wasn’t aiming for a perfectly balanced or academically pure history. He prioritized a gripping, Native-centered narrative which means he took some liberties and left out counterpoints. Some inaccuracies also stem from the limited sources available in 1970.

These points aren’t meant to dismiss the book, but to remind us that historical narratives evolve. Our understanding deepens as new evidence and interpretations emerge.

Why It Still Matters Today

Reading Bury My Heart At Wounded Knee now is like looking through a window into a critical shift in American historical storytelling. It disrupted the dominant myths and presented a more nuanced, emotional, and human story.

For people hungry to understand Native American history and the West beyond clichés, it remains a strong starting point. But it’s wise to pair it with more recent works to round out the picture.

Consider following Brown with titles like Patricia Nelson’s Legacy of Conquest or Thomas King’s The Inconvenient Indian—both offer updated perspectives and fresh insights into Indigenous history and experiences.

If you prefer something that inspired Brown’s work, Helen Hunt Jackson’s A Century of Dishonor (published in 1881) is a powerful yet different take on injustices faced by Native Americans.

Also, the 2007 HBO adaptation of Bury My Heart At Wounded Knee shines a spotlight on the Assimilation Policy. It’s available on HBO Max and serves as a complementary visual experience.

Final Thoughts: To Read or Not to Read?

If you want a book that shakes up your understanding of the American West and offers a Native-centered eye-opening perspective, then yes, this book is (still) worth reading.

But keep your critical lens sharpened. It’s not the final word on Native American history. Instead, think of it as a pivotal chapter that reopened the conversation. It invites readers to question what they’ve heard and to seek out broader stories.

Above all, the book reminds us that history is rarely simple. It is messy, painful, and full of surprising twists—much like real life.

So why not dive in? You might find yourself viewing the past, and present, in a new light. And isn’t that what a good book should do?