In Koine Greek, the words for sun (ἥλιος, helios) and son (υἱός, huios) are not used as a pun. Although these words may seem close when viewed superficially, their actual pronunciations are quite distinct. Apart from sharing common noun endings, they have little phonetic similarity. Consequently, there is no evidence in Koine Greek literature of a deliberate wordplay between ἥλιος and υἱός.

The endings of these two words are typical among many Greek nouns, so similarity in endings does not imply a pun. The roots and pronunciation differ significantly. For example, the sun-related word ἥλιος has a different vowel and consonant structure than υἱός, which denotes son.

Additional evidence comes from analysis of biblical passages like Mark 16. The phrase for the rising of the sun is ἀνατείλαντος τοῦ ἡλίου (“the sun rising”). However, the verb used for “he is raised” is ἠγέρθη, which is unrelated to the verb for rising of the sun. This indicates that the text does not exploit any pun on the concept of “rising” associated with the sun or the son.

While creating wordplays in Koine Greek is theoretically possible, no examples of puns between ἥλιος and υἱός have been found in extant literature. Scholars acknowledge the vastness of Greek literature and concede that some puns might exist but remain undiscovered. However, as it stands, no known instances of sun-son puns are documented in Koine Greek texts.

- ἥλιος (helios) and υἱός (huios) differ significantly in pronunciation beyond common noun endings.

- Their roots and phonetic components do not align to form puns naturally.

- Passages like Mark 16 show no linguistic play between words for sun rising and being raised.

- Potential for puns exists theoretically but is unsupported by current evidence.

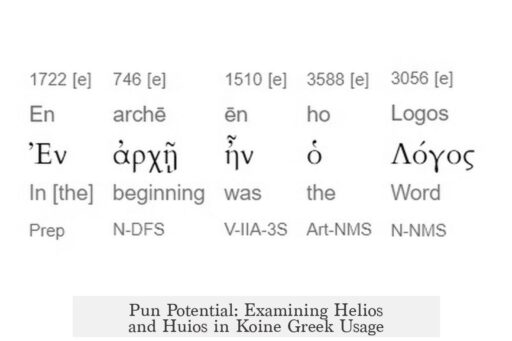

In Koine Greek, Are the Words for Sun (Helios) and Son (Huios) Ever Used as a Pun?

Short answer: No, the words ἥλιος (helios, sun) and υἱός (huios, son) are not known to be used as a pun in Koine Greek literature. Despite their seeming similarity at first glance—especially to English speakers—they don’t function as a wordplay pair in the original texts. The pronunciation, meaning, and usage lines are quite distinct.

Let’s unpack why this pun is practically nonexistent, and why the popular English play on “sun” and “son” is a very modern phenomenon. You might discover that Koine Greek, with its nuances, doesn’t quite lend itself to that charming linguistic double act.

Pronunciation: On the Surface but Far Apart

At a quick glance, helios and huios look and sound close. Both end in an “-ios” sound. But here’s where an important fact steps in: that ending is so common in Greek nouns, it’s hardly a sign of kinship.

The initial sounds create a solid divide. Ἥλιος begins with the “h” sound (rough breathing mark), and the second vowel is an eta (long “ē” sound), contrasting with υἱός, which starts with upsilon (an “u” or “ü” sound) followed by an iota diphthong. So they don’t rhyme or share much in the beginning. Pronouncing them side by side, they sound noticeably different.

Greek listeners and readers of the time would easily distinguish the two, unlike modern English ears that may lump “sun” and “son” as homophones. So any assumption about punning based on auditory similarity gets deflated.

Meaning and Usage: Too Different to Entwine Naturally

In Koine Greek, ἥλιος primarily refers to the **solar body**, the actual sun. It carries straightforward literal and sometimes metaphorical usage—light, brightness, even the idea of glory or power.

On the other hand, υἱός means “son” in a familial, religious, or metaphorical sense. It can signify literal sons, descendants, or spiritual sonship—as famously used in the New Testament regarding Jesus Christ.

Despite these thematic potentials—the sun and a son could symbolically interlock—the language doesn’t seem to indulge in twisting them together phonetically or poetically.

The “Rising” Verbs: No Punning in Mark 16

A fine place to look for wordplays involving sun and son might be Mark 16, where the “rising” theme appears both literally and metaphorically: the sun rises, and Jesus “is raised.”

However, the phrase for the rising of the sun is ἀνατείλαντος τοῦ ἡλίου, where the verb ἀνατέλλειν means “to rise.” Meanwhile, “he is raised” is ἠγέρθη, derived from ἐγείρω, meaning “to awaken” or “to raise.” These verbs are completely unrelated in roots and sounds.

This separation in vocabulary rules out any pun based on “rising” in this passage, even though English translations often invite readers to connect these ideas through the punning homophones “sun” and “son.”

Is Punning Possible in Koine Greek?

Could a clever speaker or writer create a pun on these words? Probably yes. Ancient Greeks loved wordplays and clever uses of language, after all.

But here’s the catch: despite the possibility, no known surviving Koine Greek literature—at least among the well-studied corpus including biblical texts and classical Greek writings—uses a pun combining ἥλιος and υἱός.

One expert admits this limitation openly, acknowledging that the breadth of Greek literature is massive and some lines or jokes may have escaped preservation or discovery. The absence is not absolute proof of impossibility but strong evidence that such puns were not a common or recognized literary device.

Why Does This Matter?

Understanding that **sun-son puns are absent in Koine Greek enriches how we approach biblical and ancient texts.**

- It reminds us that the English Bible translators sometimes make poetic decisions suited for English culture but not present in the original language.

- It clarifies theological or literary readings: the “Son of God” and the “sun” might share symbolic imagery but not wordplay.

- It encourages linguistic humility. Languages have unique sounds and semantics that resist direct transfer of puns or jokes.

So if you ever wondered whether the shining “Sun” in Koine texts winked at its “Son” counterpart, the answer turns out to be a polite “No thanks.”

Looking Forward: How to Spot Genuine Koine Puns

If you want to explore this fascinating linguistic playground yourself, here are a few tips:

- Focus on similar-sounding words sharing roots, not just endings.

- Look for double meanings within one root verb or noun rather than just phonetic similarity.

- Check the verbs: are they related or derived from the same root? This is often where clever plays emerge.

- Remember context and audience—ancient Greek writers often made puns that suited oral tradition and cultural references unavailable today.

Wrapping Up

In conclusion, Koine Greek does not appear to use ἥλιος and υἱός as a pun. Their phonetics, meanings, and usages occupy separate lanes with minimal overlap. The English pun on “sun” and “son” is a linguistic quirk of English speakers, not an inherited joke from the ancients.

Next time you hear a sermon or poem playing on “sun” and “son,” you’ll know it’s a clever English pun, not a Koine Greek one. Language is fascinating, isn’t it? Its subtleties surprise us and keep the ancient world alive in new ways.

Maybe someday a forgotten Greek manuscript will surface with a neat sun-son pun. Until then, we enjoy the clarity that ἥλιος shines brightly on, while υἱός stands firmly by itself—as a son’s identity deserves.

Are the words ἥλιος (sun) and υἱός (son) pronounced similarly in Koine Greek?

At first glance, they may seem similar. However, their pronunciations differ notably apart from their common noun endings. Their core sounds are distinct in spoken Koine Greek.

Does Koine Greek literature use puns based on the similarity between ‘sun’ and ‘son’?

No clear examples exist. Scholars have not found puns using ἥλιος and υἱός in surviving texts. If such wordplay was common, more evidence would likely appear in existing literature.

Can the concept of ‘rising’ be used as a pun between sun and son in Koine Greek?

Although English can pun on ‘rising,’ Koine Greek uses different verbs for these actions. For example, Mark 16 uses ἀνατείλαντος (rising of the sun) and ἠγέρθη (he is raised) which are unrelated and don’t create a pun.

Is it possible that sun-son puns exist but are undiscovered in Koine Greek?

It is possible. Greek literature is vast, and not all texts have been fully explored. Still, no known examples have surfaced to date linking ἥλιος and υἱός as puns.