The claim that samurai arrived in Mexico from 1603 onwards to work as guardsmen and mercenaries is supported by historical documentation, though the exact scale and details remain uncertain. Asians, including Japanese, began arriving in the Viceroyalty of New Spain (modern Mexico) during the early 17th century. It is estimated that between 40,000 and 60,000 Asians of various nationalities lived in New Spain over about 250 years. Some of these Asians included samurai who settled and took up roles such as guards and militia members.

One significant event supporting this is the 1614 embassy sent by Date Masamune, a powerful Japanese lord, to Spain and Rome. This embassy reached Mexico, then part of New Spain. Of the roughly 180 Japanese in this delegation, about 60 were samurai. Historical records suggest that roughly half the group remained in Mexico rather than continuing to Europe.

One documented samurai who settled in Mexico was Diego de la Barranca. He arrived from Japan, married a Spanish woman, and served as a soldier. He even earned the title “Don” and the right for himself and his descendants to wear traditional Japanese swords, reflecting his maintained cultural identity.

Additionally, Japanese merchants in Mexico, such as Juan Tello de Guzman, received permission to carry weapons like swords and daggers. This was unusual in colonial Mexico, indicating a recognized status and a need for self-protection in their commercial activities.

| Fact | Details |

|---|---|

| Estimated Asians in New Spain | 40,000 to 60,000 over 250 years |

| Year of Samurai Arrival | From 1603, notably 1614 Date Masamune embassy |

| Number of Samurai in Embassy | About 60 samurai, half stayed in Mexico |

| Example Settled Samurai | Diego de la Barranca, soldier, married Spanish, titled Don |

| Merchant with Right to Carry Weapons | Juan Tello de Guzman |

Though exact numbers and extensive records are limited, multiple credible references confirm samurai presence in New Spain. These samurai integrated into local society while maintaining some traditions, such as sword carrying. Their role as guards or militia is well documented, illustrating their function beyond mere immigration.

- Samurai arrived as part of Japanese delegations and migrants post-1603.

- Some samurai stayed in Mexico, worked as soldiers and guards.

- Individuals like Diego de la Barranca represent settled samurai integrating locally.

- Japanese merchants maintained the right to carry swords for protection.

- Overall Asian population in New Spain included significant Japanese presence.

Did Samurai Really Arrive in Mexico from 1603 Onwards?

You’ve probably heard some striking tales about Samurai arriving in Mexico during the early 1600s, working as guards or mercenaries. So, how true is this story? Yes, it’s true—Samurai did reach Mexico in the early 17th century and some even settled there as guards or militias. But let’s unpack this fascinating slice of history with some solid facts and a few captivating stories.

First, understand the backdrop. Between the early 1500s and 1800s, the Viceroyalty of New Spain (which included much of present-day Mexico) became a melting pot of people from Asia. Historical estimates suggest that over 40,000 to 60,000 Asians of various nationalities—including Japanese—set foot in the region. That’s a serious influx of Eastern presence in a largely Spanish-dominated colony.

How Did Samurai End Up in Mexico?

One of the key events linking Japanese Samurai to Mexico involves a prominent regional leader—Date Masamune. In 1614, Masamune sent an embassy to Spain and Rome, making a historic journey that included Mexico as a stopping point. This embassy had around 180 Japanese crew members, including about 60 Samurai warriors.

Here’s the twist: half of these Samurai chose to stay behind in Mexico rather than continue to Spain or Rome. Why would they do this? Well, crossing oceans at that time was risky enough, and the prospects of a new life in New Spain possibly offered better opportunities or safety. Mexico, bustling as a colonial hub, was welcoming these foreigners as part of its dynamic society.

Guardians of the New World

Not all of these Samurai just retired quietly. Many found employment as guards or militias. This was logical—Samurai training made them perfect candidates for military roles. Records note several Asians employed as guards or militia members, securing estates or colonial buildings. Their skills with the sword and disciplined nature would have been valued assets. Imagine a Samurai standing watch in a colonial Mexican fortress—that’s history blending worlds.

One prominent individual was Diego de la Barranca. From a place known as “the canyon” in Japan, Diego stayed behind in Mexico. He married a Spanish woman, served as a soldier, and earned the honorable title “Don.” The Spanish crown even allowed him and his descendants the right to carry Japanese swords—a privilege that most foreigners did not enjoy.

Merchants with a Sword

Beyond warriors, some Japanese in Mexico were merchants who needed protection. Juan Tello de Guzman, a Japanese merchant, was permitted to carry a sword and dagger while selling goods outside Mexico City. This rule wasn’t handed out lightly. It shows respect for the merchant’s status as well as recognition of the potential danger he faced. If you imagine bustling colonial markets, you might picture Juan navigating the crowds with his blades safely sheathed but ready if trouble came knocking. This detail humanizes the Asian presence in New Spain, making it more vivid.

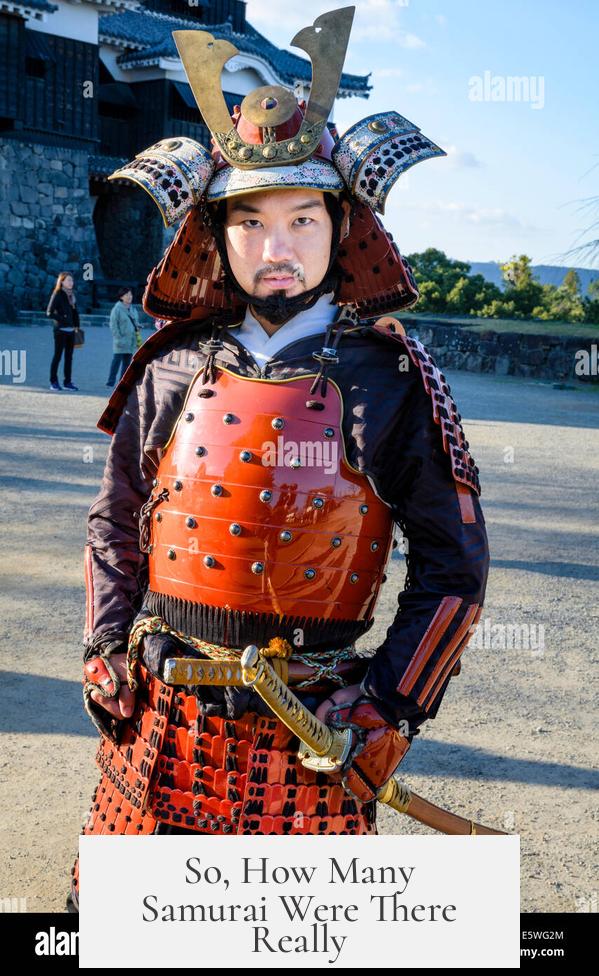

So, How Many Samurai Were There Really?

The exact number of Samurai who lived and worked in Mexico is unknown, but some facts help us estimate. From Date Masamune’s embassy alone, about 60 Samurai arrived, and roughly half stayed. Including other Asians landing in New Spain across decades, numbers could reflect a few hundred Samurai at most, part of the broader Asian immigrant population.

These Samurai integrated into colonial society, sometimes marrying locals, adopting Spanish names, and blending cultures. They contributed to the heterogeneous and multicultural fabric of early Mexico. It’s not like you would spot them daily, but their legacy survives in family stories and historical records.

What Does This Mean Today?

Why does this matter? Well, the presence of Samurai in Mexico challenges many assumptions about colonial history. Most people think of Spanish conquistadors or indigenous populations, but here’s an often-ignored Asian connection. It also shows globalization isn’t new; even 400 years ago, people crossed oceans, cultures mixed, and identities evolved in unexpected ways.

For history buffs or anyone fascinated by multicultural stories, this chapter is a gem. Imagine telling your friends that your local Mexican history includes noble Samurai with swords and Spanish titles! It’s proof that history holds surprising tales just waiting to be discovered.

Takeaway & Final Thoughts

Yes, Samurai arrived in Mexico starting around 1603, particularly following Date Masamune’s embassy in 1614. Many stayed and found roles as guards, soldiers, and merchants. The largest group’s size isn’t precisely known, but their impact, while subtle, is documented and admired by historians.

If you’re curious to dig deeper, here’s a tip: look for local Mexican archives or books on Asian diaspora in Latin America. You’ll find stories of immigrants like Diego de la Barranca that add rich layers to the narrative.

So, next time someone doubts the Samurai presence in Mexico, you can confidently share this fascinating melding of cultures — a chapter where Samurai swords clashed, not just in Japan, but across the Pacific too.

“History is not just about dates and places; it’s about the blending of cultures that defy borders. The Samurai in Mexico are a perfect example.”

Have you ever come across other surprising historical crossovers like this? Drop a comment or share your favorite surprising history fact!