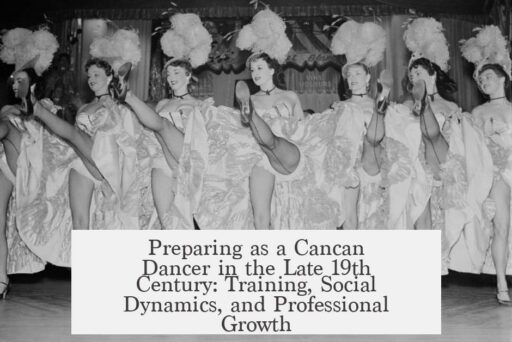

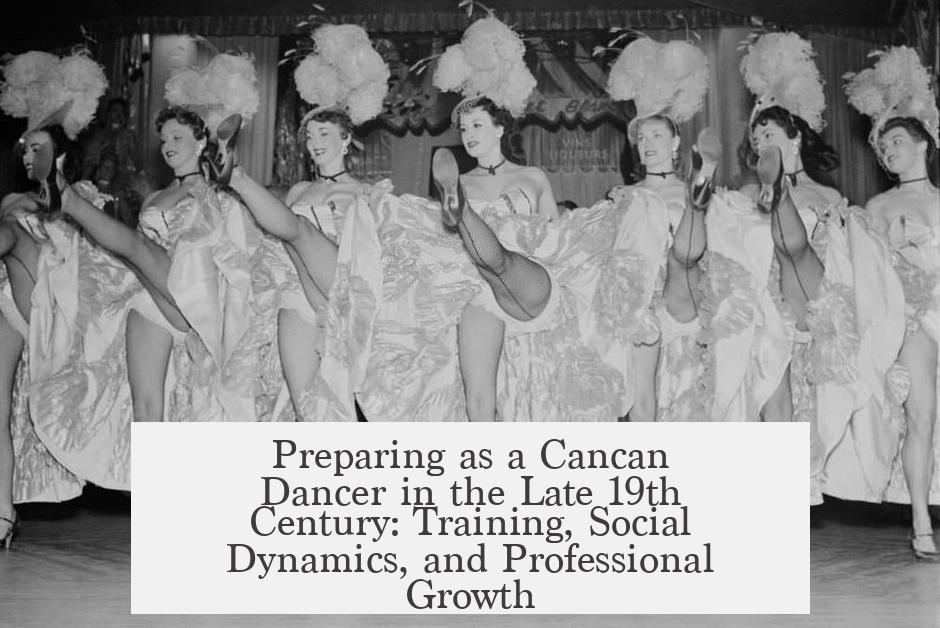

As a cancan dancer in the late 19th century, preparing for this profession involved rigorous physical training, navigating complex social stigmas, and intense professional discipline.

Back then, being a female stage performer was socially frowned upon. Society often associated female entertainers with immorality or sex work. Many dancers were forced into precarious positions, sometimes relying on wealthy patrons or turning to prostitution to survive. This social context created challenges that dancers had to overcome beyond the dance floor.

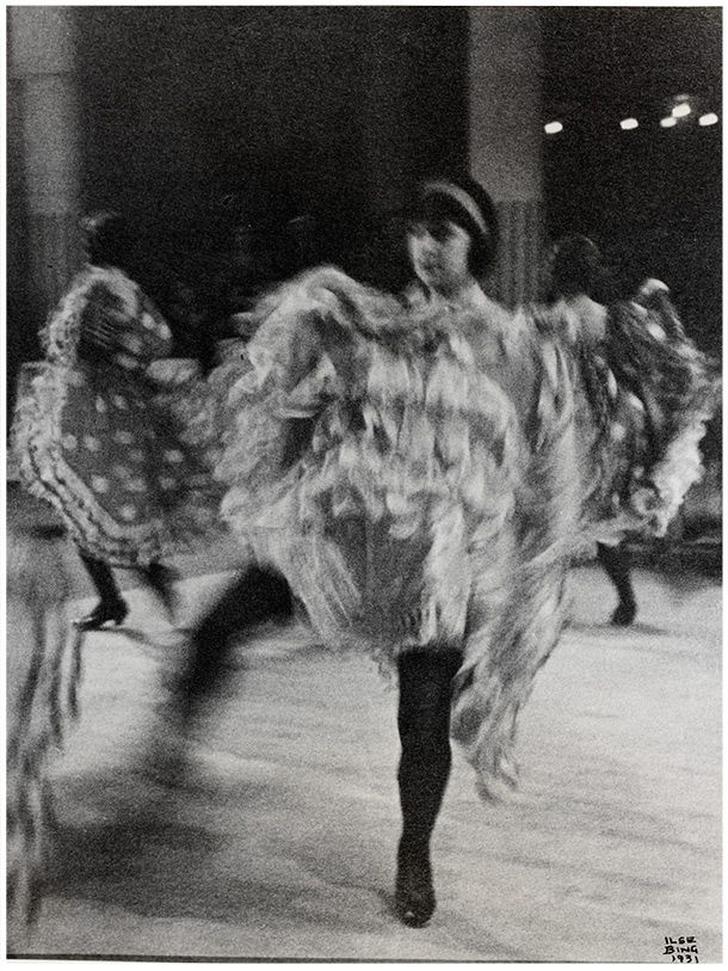

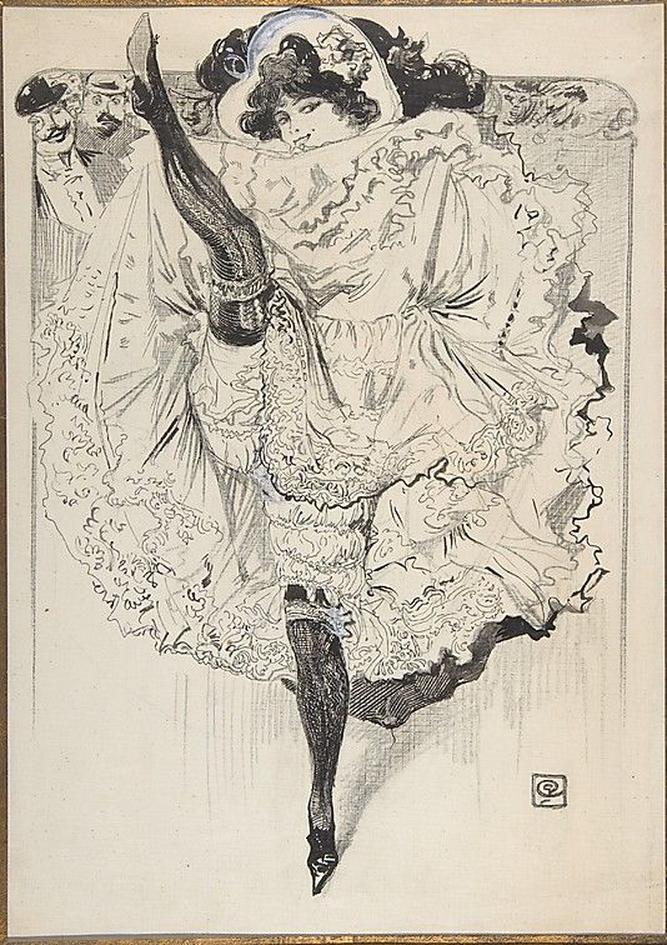

The cancan was a highly provocative and physically demanding dance. Originating in the early 19th century, it was viewed as indecent and often banned. The dance featured high kicks, splits, and energetic movements that required strength and flexibility. By the mid-1800s, the cancan emerged from informal dance halls into more formal establishments, transforming into a professional stage performance.

Preparation involved specialized training, often under experienced choreographers and instructors. Some dancers, like the apocryphal Joséphine Durwend (Finette), received lessons at prestigious places such as the Paris Opera. She reportedly studied with masters Henry Cellarius and Markowski, both important figures who trained leading dancers of the era. Such training focused on mastering high-kicks, splits (grand écart), stamina, and expressiveness on stage.

Skills required to perform the cancan went beyond basic dance ability. Dancers needed strong legs and excellent balance for the vigorous jumps and kicks. The dance’s pantomime elements demanded theatricality and endurance. Training was physically intense to sustain multiple energetic performances.

Often, dancers came from working-class origins. The Paris Opera trained many children, known as “Petits Rats,” from poor families. Their training was grueling but offered an escape from factory work, albeit with low pay and harsh conditions. Many hoped to attract wealthy patrons or find social advancement through their profession. The connection between dance and courtesanship was common, with some dancers becoming famous courtesans, blurring lines between performance and social survival.

The venues evolved from small suburban guinguettes to luxury dance halls like Bal Mabille. These places served as both entertainment sites and social hubs, influencing the dancers’ careers economically and socially. Despite challenges, cancan dancers gained celebrity status, with notable figures like Elise Sergent (Reine Pomaré) and Élisabeth-Céleste Vénard (Céleste Mogador) achieving fame.

Periodic sociopolitical upheavals affected the cancan scene. For example, the Franco-Prussian War in 1870 ended the grandeur of the Second Empire era. Many dance venues closed, and the cancan saw a decline, disappearing from mainstream entertainment for about 15 years before resurging.

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Social Challenges | Stigma against female performers; links to sex work; reliance on patrons |

| Training | Lessons at ballet schools or dance studios; focus on high kicks, splits, stamina |

| Dance Features | Energetic, frantic pace; high kicks and grand écart (splits); theatrical pantomime |

| Economic Background | Mostly working-class origin; dancers sometimes also courtesans |

| Social Setting | Dance halls ranging from guinguettes to luxury venues; celebrity dancers emerged |

| External Impact | Sociopolitical events caused fluctuations in popularity and venue availability |

In essence, preparation for a cancan career involved mastering physically demanding dance techniques under professional guidance. Dancers needed resilience to face social disdain, economic hardships, and complex roles that extended beyond the stage. The profession blended artistry with survival strategies on all fronts.

- Cancan dancers faced social stigma and potential exploitation.

- Training included lessons at ballet schools or studios under notable masters.

- The dance demanded high-kicks, splits, stamina, and theatricality.

- Dancers often originated from humble backgrounds.

- Links to courtesanship and patronage were common paths.

- Fluctuating political climates impacted dance venues and fortunes.

How Did I Prepare Myself as a Cancan Dancer in the Late 19th Century?

Being a cancan dancer in late 19th century France meant more than just mastering high kicks and splits—it meant navigating a challenging social labyrinth and physical rigor without the modern comforts of fame or respectability. This profession demanded tough preparation physically, socially, and emotionally. Let’s peel back the layers of history and reveal how cancan dancers like me prepped to bring excitement to Paris’ wild dance halls.

First off, the life of a female stage performer in 19th century France was no cakewalk. Society viewed female performers through a harsh lens. The stage wasn’t a respectable career for women unless they came from families entrenched in show business—and even then, the stigma lingered. Most “honest” women stayed home or took on roles that society deemed suitable—like marrying, becoming widows, or entering convents. Women who danced professionally were often equated with sex workers, a comparison fueled by exploitative theatre managers who controlled and mistreated them.

The environment was grim. Managers imposed fines, and dancers frequently had to purchase their own costly costumes and jewelry, plunging many into debt. Many dancers turned to prostitution simply to survive, sometimes pressured by the very men who hired and managed them. This dynamic blurred the line between performer and sex worker, making training not only a matter of perfecting dance but also surviving a harsh, exploitative social reality.

Starting Young and Dancing Hard: The Road from School to Stage

Girls aspiring to be dancers often started training at a young age. In Paris, the Opéra de Paris’ School of Dance accepted children known as Petits Rats—little rats who endured hunger, poverty, and grueling rehearsal schedules. These dancers mostly came from poor families who saw dance as a preferable alternative to factory work. While some of these girls dreamed of upward mobility or finding a protector through their craft, many remained trapped in hardship.

For a typical cancan dancer outside the prestigious Opéra, formal training came from less reputable but essential dance masters. I’d apprentice under choreographers like Henry Cellarius or Markowski, figures known for pushing daring, risqué performances. Markowski’s need to frequently relocate his studio after accusations of wild parties hints at the lively, often scandalous environment that shaped our art. These lessons were grueling but crucial, transforming basic movement into the spectacular high-energy choreography demanded at places like the Bal Mabille and Jardin d’Hiver.

Mastering the Cancan: The Dance Itself

The cancan, called the chahut or quadrille exotique in earlier days, started as a rowdy dance among ordinary folk. It was anything but decent. By the 1830s, law enforcement labeled it as vulgar and often stopped performances. Early cancan featured wild high kicks, splits, and galops. These moves required incredible flexibility and stamina.

Training meant endless practice of the grand écart (the splits) and high-kicks until they became second nature. Physically, dancers needed strong legs, excellent balance, and an unyielding spirit. Practicing these moves might have involved stretching in cold rehearsal halls without modern training amenities.

But dancing the cancan was more than physical preparation. It was about mastering the art of spectacle and sensuality without crossing the societal line into outright scandal. My movements had to be bold enough to thrill but controlled enough to maintain a semblance of respectability in a hostile climate.

More Than a Dance: The Social Game

Preparing for the profession wasn’t just about perfecting steps. Networking played a big role. Female dancers often mingled with wealthy patrons and courtesans, hoping to secure a protector or rich admirer who could support them financially. This relationship sometimes translated into better access to training or glamorous costumes. It’s no coincidence that renowned dancers like Céleste Mogador also worked as courtesans.

Therefore, as a dancer, I had to develop social skills along with physical ability—learning to navigate a world where flirtation and charm were part of survival. A clever dancer could improve her living conditions by weaving relationships with patrons who offered more than empty applause.

From the Streets to the Stage: Professionalizing the Cancan

By the 1860s, venues like the Bal Mabille made the cancan a spectacle for upper-class entertainment. The dance professionalized, requiring trained female performers capable of executing precise yet wild choreography. It was no longer a spontaneous street dance in Parisian suburbs but a choreographed showpiece.

This shift meant rehearsing carefully and repeatedly to synchronize moves, maintain energy, and execute dangerous tricks like jumps and splits flawlessly. Dancers like me would practice for hours daily, refining muscle memory and endurance.

The Double-Edged Sword of Fame and Decline

During the Second Empire, the cancan’s popularity skyrocketed. French dancers inspired foreign troupes and even made their way to England, Russia, and the Americas. Yet, fame did not protect dancers from hardship or social disdain. The Franco-Prussian War in 1870 ended the opulent lifestyle associated with the dance, causing many entertainment venues to shutter.

The dance lingered in smaller halls but lost its glamorous cachet, which meant dancers had to prepare for instability in their careers. Those talented and resilient enough could survive, but many could not.

What Does This Mean for a 19th Century Cancan Dancer Today?

The story of preparing as a cancan dancer paints a complex picture. It’s a tale of incredible physical discipline intertwined with navigating social danger. Dancing the cancan meant living on the edge—physically pushing limits, socially balancing stigma and survival.

In hindsight, what lessons can we draw from this fiery profession?

- Physical Training: The importance of rigorous, focused training to master challenging choreography.

- Social Skills: Navigating social networks to secure support, highlighting how career success involves more than talent alone.

- Resilience: The need for mental and emotional toughness to endure a profession stigmatized by society.

So next time you see a cancan performance, remember the hidden stories beneath the high kicks—a story of determination, survival, and art born from adversity.

“The cancan is the art of lifting one’s skirt, the chahut the art of lifting one’s leg.” — Auguste Vermorel, 1860

Behind every daring dancer’s smile, there’s a history of sweat, strategy, and survival.

How did I learn the technical skills required for the cancan?

I trained with dance masters like Henry Cellarius and Markowski. They taught high-kicks and splits, the main moves of the cancan. Lessons could be paid for by patrons or lovers.

What kind of social environment did I face as a cancan dancer?

Stage actresses, including cancan dancers, were seen as barely respectable. Many were associated with sex work to survive due to theater pressures and social stigma.

Where did cancan dancers usually train during the late 19th century?

Some trained at places like the Opéra de Paris or private studios. Famous masters moved their studios often due to accusations of wild behavior linked with their lessons.

Did economic background affect how I prepared as a cancan dancer?

Yes. Many dancers came from poor families. Dancing was an alternative to factory work, and families hoped their daughters would find protectors or husbands through the profession.

How did cancan transform from a public dance to a professional show?

By the 1840s, larger venues like Bal Mabille turned cancan into a staged performance. It required skilled dancers able to do demanding moves like jumps and splits.

Was there any patronage or support involved in my training?

Some dancers had wealthy lovers who paid for lessons and costumes. Patrons helped dancers survive the costly and demanding nature of the profession.