Ancient Greeks understood the myth of Persephone as a story of forcible abduction by Hades, marked by trauma and lack of consent, despite legal approval from Zeus, her father. The narrative centers on Persephone’s unwillingness and Demeter’s grief, emphasizing the harsh reality of the event rather than acceptance or ritual symbolism.

Every surviving ancient Greek literary work or artwork that recounts Persephone’s story depicts Hades as forcibly taking her. The myth contradicts modern misconceptions that Persephone went willingly. Key ancient sources confirming the abduction’s forcefulness include Hesiod’s Theogony (lines 912–914), the Homeric Hymn 2 to Demeter, and various vase paintings showing the violent nature of the event. Later Roman authors like Ovid in Metamorphoses and the Bibliotheke of Pseudo-Apollodoros reaffirm this understanding.

The abduction is not merely a marriage ritual or symbolic act. In ancient Greece, some marriage customs involved a ritualized, pretend abduction. For example, Ploutarchos of Chaironeia records such a custom in Sparta. However, no ancient text links Persephone’s myth to this custom. On the contrary, the sources highlight her distress and resistance, distinguishing the myth from these ritual enactments.

Legally, the abduction had Zeus’s consent, reflecting ancient Greek marriage norms where the father’s approval sufficed for a valid union. Neither Persephone’s nor her mother Demeter’s consent was necessary. Thus, Hades’ act had divine sanction, yet it did not diminish the evident lack of Persephone’s willingness or Demeter’s sorrow. This legal background helps explain why Zeus approved Hades’s abduction while the narrative simultaneously preserves Persephone’s trauma.

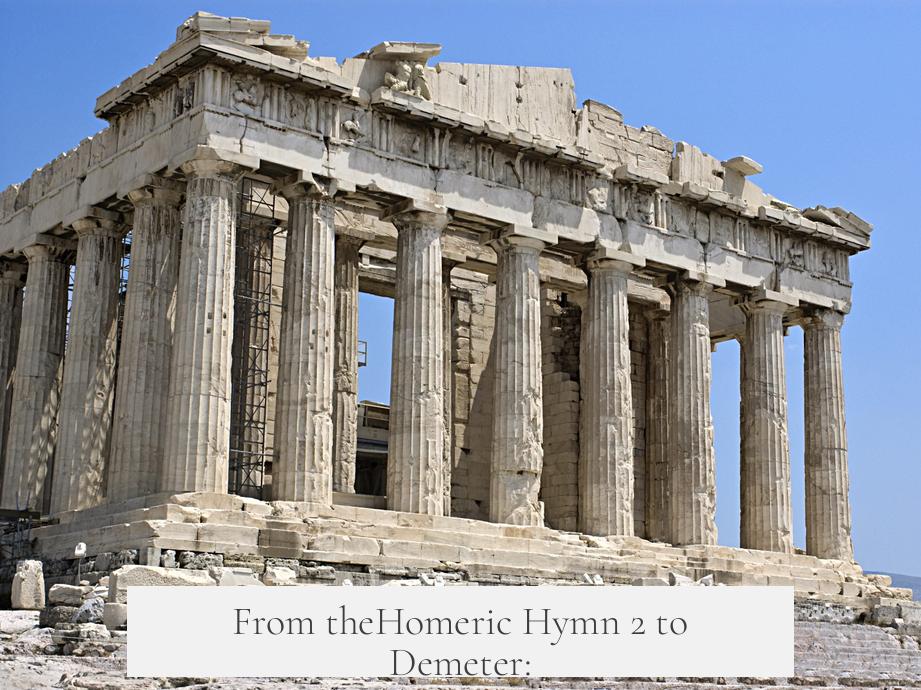

From the Homeric Hymn 2 to Demeter:

“and her long-legged daughter whom Hades snatched (loud-rumbling, thundering Zeus gave her away) while she played with the virgin daughters of Ocean, far from Golden Grain Demeter… Out sprang Lord Hades… Snatching the unwilling girl, he carried her off …as she cried and screamed aloud calling to her father … None of the immortal gods or mortal folk heard her cry … except Hekate and Helios… Zeus sat far away… Lord of the Dead, stole the unwilling girl… with a nod from Zeus.”

This passage reveals the intense emotional suffering of Persephone and the sorrow of Demeter searching for her daughter. The grief of both figures is central and underscores the violent and non-consensual nature of the abduction rather than portraying it as a benign event.

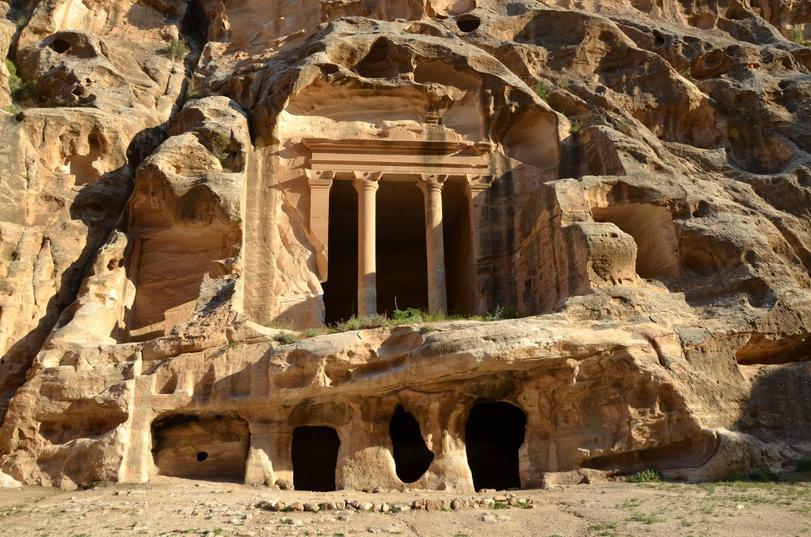

Ancient artwork mirrors these literary descriptions, frequently showing Persephone struggling against Hades as he forcibly carries her away. This visual evidence complements the texts, forming a consistent picture of trauma and grief.

The myth, therefore, represents a complex interplay of divine authority, human emotion, and social values around marriage and consent in the ancient Greek world. It reflects tensions between male power sanctioned by Zeus and the female experience of loss and violation through Persephone’s perspective.

The enduring story may have served to explain natural and seasonal cycles, linking Persephone’s descent to the underworld with winter’s barrenness and her return with spring’s renewal. Yet, the ancient Greeks did not obscure the grim reality of the abduction’s violence within the myth.

| Aspect | Ancient Greek Understanding |

|---|---|

| Nature of Abduction | Forcible, non-consensual, traumatic |

| Legal Dimension | Sanctioned by Zeus, father’s consent sufficed |

| Persephone’s Consent | Not given, her resistance emphasized |

| Mother’s Role | Demeter deeply anguished, opposes Hades’ act |

| Marriage Ritual Comparison | Myth does not reflect ritualized pretend abduction |

In sum, the ancient Greeks saw the myth of Persephone as an event of harsh divine will overriding personal choice. It showed the limits of female agency in marriage while underscoring profound emotional pain. This comprehension shaped the myth’s lasting place in Greek culture and its interpretations.

- Persephone’s abduction by Hades was depicted as forced and traumatic.

- Zeus’s consent legitimated the marriage legally, not emotionally.

- Sources strongly oppose the idea of Persephone’s willing departure.

- Ancient marriage rituals involving pretend abductions do not apply here.

- Demeter’s grief and Persephone’s distress are central narrative elements.

How Would Ancient Greeks Have Understood the Myth of Persephone?

If you’re imagining the ancient Greek myth of Persephone as a sweet romance with her willingly eloping with the god Hades, think again. The ancient Greeks understood this story very differently. They saw it as a forceful, traumatic abduction, one fraught with pain, grief, and very little, if any, consent from Persephone herself.

Let’s dive into what makes this myth so powerful and complex to the ancient world’s eyes—why it was about abduction, emotional anguish, and social rules, not about romantic consent.

Persephone’s Abduction: Force, Not Fancy

Despite some modern misconceptions, there is zero evidence in ancient Greek or Roman sources that Persephone gleefully hopped into Hades’ chariot. On the contrary, every surviving literary text and piece of art from the era portrays the abduction as harsh and uninvited. Hades essentially swoops in like an ancient version of a villainous carjacker—without permission.

- Hesiod’s “Theogonia” (7th century BCE) directly depicts Hades grabbing Persephone without consent.

- The Homeric Hymn to Demeter dramatizes her desperate cries and reveals how she struggled, screaming for help during the kidnapping.

- Various vase paintings and mosaics consistently show a forceful abduction scene.

- Even later Roman writers like Ovid in Metamorphoses confirm the same narrative.

To put it bluntly: Persephone did not smile and wave goodbye. She was ripped away—traumatized and helpless.

Marriage Rituals? Not in This Story

Some might wonder if this abduction was part of an ancient Greek ritual—a “pretend” abduction like those recorded in Sparta’s state rituals where brides were symbolically “taken” to their husbands. But the mythmakers didn’t go down that path with Persephone’s story.

Ploutarchos of Chaironeia does record a ritualized abduction in marriage, but nowhere do any sources indicate that Persephone’s story is a symbolic rite. Instead, they emphasize raw trauma and unwillingness. That sets Persephone’s myth firmly apart from these ritual practices.

Father Knows Best: Zeus’s Role in the Abduction

Here’s a grim glimpse into how marriage worked back then: The consent that mattered was that of the father. Zeus, Persephone’s dad, technically gave Hades permission for the abduction and the forced marriage.

In the ancient Greek world, the bride’s feelings were, unfortunately, legally irrelevant. Even Persephone’s mother, Demeter, had no legal say. Zeus’s nod is what sealed the deal.

This means the myth reflects a social reality where patriarchal permission overrides personal choice. So, while the abduction was legally accepted, Persephone’s will wasn’t considered important.

The Agony of Separation: Demeter and Persephone’s Grief

We can’t look at Persephone’s myth without talking about Demeter’s unbearable pain—the grief that tears at the seasons themselves.

The Homeric Hymn to Demeter captures this beautifully in a way that’s impossible to ignore:

“…and her long-legged daughter whom Hades snatched (loud-rumbling, thundering Zeus gave her away) while she played with the virgin daughters of Ocean, far from Golden Grain Demeter… She picked lush meadow flowers… a chasm opened… Out sprang Lord Hades… Snatching the unwilling girl, he carried her off …as she cried and screamed aloud calling to her father …”

This passage doesn’t read like a fairy tale. It shows a frightened girl seized by a god, her cries unheard except by a few divine witnesses. Demeter’s subsequent search, sorrow, and refusal to let the earth bear fruit without her daughter illustrate the deep anguish that grips the story.

The ancient audience likely understood this as a grave tragedy. Zeus and Hades made a cold political decision, ignoring the emotional wreckage it wrought.

So, What Can We Learn From This Ancient Tale?

The myth of Persephone isn’t about willing bride-to-be excitement or a neat symbolic wedding ritual. Instead, it is a profoundly disturbing story of forced marriage, highlighting the limited agency women had in ancient Greek society.

It also reflects on themes of loss, trauma, and the emotional cost borne not only by Persephone but also by Demeter—the goddess who embodies fertility and the earth’s bounty. The myth explains why seasons change through Demeter’s grief-stricken withdrawal from the earth during Persephone’s time in the underworld.

If ancient Greeks saw the abduction as traumatic, why did it become such a central myth? It offered a divine explanation for the natural cycle, but also reinforced social norms about marriage and authority. Persephone’s story lived as a cautionary, poignant reflection on fate, authority, and the struggles faced by women.

Reflecting on Ancient vs. Modern Views

Today, some voices might downplay the trauma or portray Persephone’s story as a romantic elopement. However, ancient evidence shows a very different picture—one that resists sugarcoating or mythologizing abduction as acceptable.

Understanding this shifts how we interpret the myth and respect the emotional truths embedded in it. It reveals ancient Greeks’ grappling with dark themes of power, consent, and emotional suffering long before modern discourse took hold.

It also raises questions: How do myths shape societal views on relationships and consent? What can we learn by confronting the raw, sometimes uncomfortable truths in these stories?

Summary: The Ancient Greek Understanding of Persephone’s Myth

- The abduction was violent, non-consensual, and traumatic for Persephone.

- This was not a ‘ritual’ abduction but a grim, literal kidnapping.

- Zeus’s consent made the abduction legally justified, not Persephone’s or Demeter’s.

- Emotional anguish of Persephone and Demeter is central—highlighting trauma, not acceptance.

Through this lens, the myth reveals a more serious side of Greek mythology—a story where grief and injustice intertwine with divine power and natural cycles. Ancient Greeks did not miss the sorrow hidden beneath the myth’s surface. Neither should we.