Before industrialization, printed books were mass produced using manually operated flat-bed printing presses. These presses, stemming from 15th-century designs, involved pressing inked movable type against paper sheets to transfer text and images. Despite their mechanical simplicity, these presses could create multiple pages at once, allowing early print shops to produce dozens of complete books daily.

Printing technology in the pre-industrial era refers to the period before the 1840s, before the full impact of the Second Industrial Revolution. During these centuries, the fundamental design of printing presses changed little. The common press consisted of a flatbed where typesetting was locked into place, covered with ink, and pressed against paper using a screw-operated wooden platen.

The operation of these presses involved several steps. First, the typesetter arranged individual movable metal letters to form the pages. The fully set type block, inked with a thin coat of printing ink, lay flat on the machine. Printers placed sheets of paper on top, slid the bed beneath the press, and applied pressure by turning the screw handle to press the paper onto the inked type. Finally, the platen was raised, and the freshly printed sheet removed.

This process demanded a division of labor within printing shops. Typesetters required literacy and skill to arrange the tiny movable type. By contrast, press operators only handled the mechanical work of loading paper and turning the press’s handle. Folding and binding, crucial post-printing tasks, often took place in separate workshops, sometimes staffed by apprentices and students.

The output of one of these presses varied. Estimates suggest a single press might produce roughly 1,200 to 1,600 impressions during a 15-hour workday, equating to a print every 45 seconds. This rate accounts for pauses needed for ink replenishment, adjustments, and rest breaks. Absolute upper limits reach near 3,600 prints, but such figures are unlikely due to physical constraints and wear on equipment.

Books were not printed one page at a time but in larger sections called signatures. A single sheet could print multiple pages, depending on folding methods and book size. For example, in an octavo format (about 6 by 9 inches), one sheet could be folded to produce 16 pages of a book. A 240-page book would require approximately 15 signatures.

Calculating printing times, it took about 45 seconds per sheet for one side, so printing both sides of a signature took roughly 1.5 minutes. Producing an entire 240-page book with a single flat-bed press took around 22.5 minutes. In 12 hours, a single press could produce about 25 copies of that book.

To increase volume, large print shops operated multiple presses simultaneously. It was common for shops in regions like Poland and Germany to have between four and fifteen presses. A dozen presses working in tandem could produce hundreds of copies daily, enough to meet the demand for books, pamphlets, and newspapers of the time.

Minor mechanical innovations improved the presses before the industrial revolution. For instance, the screw mechanism was gradually replaced by a knuckle lever that simplified the press motion. Wood components slowly gave way to cast iron, increasing durability and strength. Small-scale presses were also miniaturized for printing leaflets.

With the arrival of the 1830s and 1840s, steam-powered and semi-automated presses emerged. Innovations included automatic ink rollers that spread ink evenly onto type, reducing manual labor. The Boston-type press by Isaac Adams incorporated steam power, marking a shift toward faster mechanized printing.

The major leap came with the invention of rotary presses. Early models by Friedrich Koenig and Andreas Bauer (1811) used a rotating cylinder pressing paper against a flat typebed. The 1814 double-cylinder version improved speeds from 800 to 1,200 prints per hour. These machines found early success printing newspapers, like London’s Times, which required rapid production of around 1,500 copies per edition.

Further developments by Augustus Applegath and Richard March Hoe introduced rotary cylinders fully integrating movable type and automated inking. By 1828, presses could print up to 4,000 sheets per hour. These advances paved the way for the mass-produced print culture central to industrial societies.

Before these rotary innovations, mass production of books relied on multiple flat-bed presses worked by skilled teams. Even with limited speeds per machine, combined workshop efforts allowed large print runs. A single manual press could produce dozens of books daily; with multiple presses, hundreds were possible.

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Press Type | Screw-operated flat-bed press |

| Printing Method | Movable type inked and pressed onto paper sheets |

| Pages per Sheet | 2 to 16, depending on size (folio, octavo, etc.) |

| Output Rate | Approx. 1200-1600 prints/15 hours per press |

| Copies per Day (1 press) | ~25 copies of 240-page book |

| Workshop Scale | 4-15 presses; up to hundreds of copies daily |

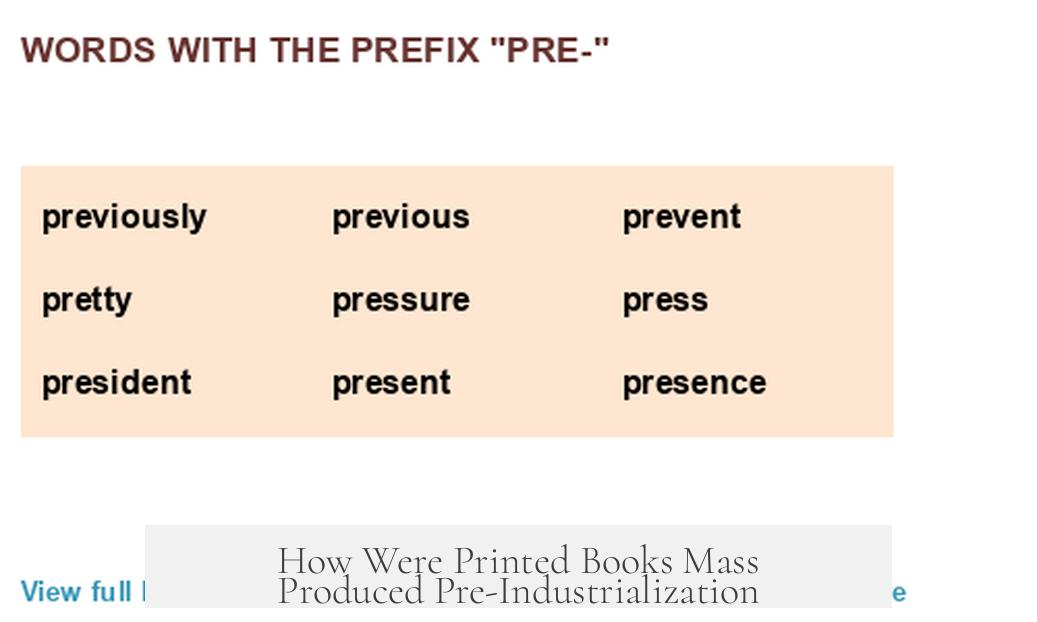

- Pre-industrial book printing used flat-bed screw presses largely unchanged for centuries.

- Books printed multiple pages per sheet, folded into signatures for binding.

- Typical printing speed allowed about 25 copies of an average book per press daily.

- Workshops employed several presses and specialized roles to increase output.

- Early 19th-century advances introduced semi-automation and rotary presses, speeding production further.

How Were Printed Books Mass Produced Pre-Industrialization?

Mass production of printed books before industrialization was a meticulous and moderately efficient process relying predominantly on manually-operated flatbed printing presses and skilled division of labor in workshops. This era, spanning roughly from the 15th century up to the early 19th century before the so-called Second Industrial Revolution (before the 1840s), witnessed the gradual evolution of printing but no radical mechanical leaps until steam power and rotary presses emerged.

So then, what exactly did this mass production look like before mechanization churned things into hyper-drive? Let’s unpack the fascinating story of how printers managed to meet demand using slow but painstakingly refined manual methods.

Pre-Industrial Printing: A Flatbed Affair

For about 400 years—from Gutenberg’s groundbreaking press in the mid-1400s through the early 1800s—European printing technology stuck to the flatbed press design. Think of it as the “classic” printing machine.

This basic device consisted of a flat frame where the text (set in movable type) lied flat. Paper sheets were carefully placed on top, then pressed down using a large screw-operated wooden platen. Operators had to apply ink thinly to the raised type, position the paper exactly, slide the whole bed under the press, turn the screw to press the sheet, and then peel off the freshly printed page.

That’s a lot of steps just for one sheet, but hey — Rome wasn’t built in a day, and neither were printing empires.

Skills and Division of Labor

These presses weren’t solo gigs. Small commercial workshops typically employed a crew:

- Typesetter: This was a highly skilled and literate role, arranging tiny individual letters made of metal (movable type) into words and lines. Typesetters had to be fast and flawless because a mistake meant redoing the entire set.

- Press Operators: Often illiterate workers handled the pressing process, which was more manual labor than brainwork. It required strength and consistency.

- Binders and Foldings: Students and apprentices mostly handled folding the printed sheets into “signatures” and assembling them into books, sometimes in separate binding shops.

This division ensured the steady flow of printed material despite the slow press speed.

How Fast Could They Print?

Now, the big question: how many copies could one press crank out during a long day?

Optimistic estimates from historical researcher Wolf suggested about 3,600 prints in a grueling 15-hour day—one every 15 seconds. Sounds like modern assembly line speed, right? But reality seems more grounded:

- Lower estimates suggest 1,200 to 1,600 prints per 15 hours (roughly one print every 45 seconds).

- Printed sheets required periodic breaks—for ink refills, adjusting machinery, inspections, and rest.

- Older and heavily used presses slowed the pace further.

So, a realistic pace was about one sheet every 45 seconds, which already demands respect given the manual process involved.

Pagination Magic: Printing Multiple Pages at Once

Books were never printed page-by-page. Layout experts designed “impositions” where sheets held multiple pages printed at once. For example:

- Typical large sheets measured about 24″ x 18″ (folio size).

- These sheets were folded multiple times to create “signatures” with 8 or 16 pages per sheet.

- An octavo book (approx. 6″ x 9″) typically had each sheet folded thrice—yielding 8 pages per side, or 16 printed pages total.

For example, a 240-page octavo book would require 15 such signatures.

This technique drastically sped up production since one press stroke printed multiple pages simultaneously.

Putting Output into Perspective

Let’s do some math fun:

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Time per sheet (both sides) | ~1.5 minutes |

| Time per 15-signature book (240 pages) | ~22.5 minutes |

| Books per 12-hour day (one press) | ~25 copies |

Thus, one press in a large workshop could produce roughly 25 complete books per day, an impressive feat for manual labor!

Scaling Up: Workshops and Multiple Presses

Most large shops didn’t stop at one press. Historical data from Poland and Germany reveals many printing houses operated between 4 and 15 presses simultaneously.

A dozen presses multiplying the output could churn out hundreds of copies daily—a credible mass production for the time.

Small Changes, Big Impact: Gradual Improvements

Few mechanical breakthroughs took hold before industrial power arrived. Instead, printers refined existing tech:

- Replacing the slow screw mechanism with a knuckle lever made pressing easier and more even.

- Wooden press parts slowly gave way to sturdier cast iron frames, improving durability.

- Miniature presses printed leaflets and tiny pamphlets, speeding up smaller runs.

Mini-revolutions kept the press useful but didn’t transform mass production levels dramatically.

Entering the Steam Age: Mechanization’s Dawn (1830s–1840s)

The real change came in the 19th century with early mechanization:

- In 1830, Isaac Adams built a small press type in Boston that integrated automatic ink rollers spreading ink evenly on type.

- Adams later adapted this press for steam power, letting the machine take care of much physical effort.

Actions were simplified to only placing sheets and operating the crank, ramping up printing speed and reducing fatigue.

Rotary Presses: The Game Changer

Printing’s true quantum leap arrived with rotary cylinder machines introduced by Friedrich Koenig and Andreas Bauer in the early 1800s:

- The 1811 model used a rotating cylinder to press sheets against a flat matrix, already surpassing flatbeds in speed.

- A 1814 upgrade added a second cylinder, pushing output to 1,200 prints/hour.

- These presses became indispensable to newspapers, like London’s Times, printing about 1,500 copies per issue swiftly.

- Augustus Applegath and Richard March Hoe’s rotary machines further innovated by putting movable type on rotating cylinders with continuous inking mechanisms.

- Hoe’s 1828 version could print 4,000 sheets per hour—unheard of before!

These machines laid the foundations for explosive growth in printed material worldwide.

Summing It Up: Pre-Industrial Mass Production, Not So Primitive After All

It’s tempting to imagine pre-industrial book production as painfully slow and scarce. Yet, even manually-operated flatbed presses like Gutenberg’s were capable of producing two dozen copies of average books daily. Multiply this by several presses working in tandem, and output reached hundreds of copies daily.

The combination of multiple presses, skilled labor division, and pagination-imposed layouts made “mass production” possible, even if far from today’s digital printing speed. Small mechanical innovations and miniaturized presses further contributed slowly until steam and rotary presses revolutionized print in the 19th century.

Next time you flip through an old printed book, remember: it’s a testament to centuries of smart, patient craftsmanship long before machines whirred on steam power.

Got Questions? Let’s Reflect!

- What would it have felt like to be a typesetter racing against time to compose perfect pages?

- How did the gradual shifts in technology shape literacy and knowledge dissemination before industrialization?

- Can manual craftsmanship sometimes outrun machines in quality, even if not in quantity?

Understanding the pre-industrial mass production of books reveals both the ingenuity and endurance behind the printed word, shining a light on how one invention changed the world slowly, but surely.