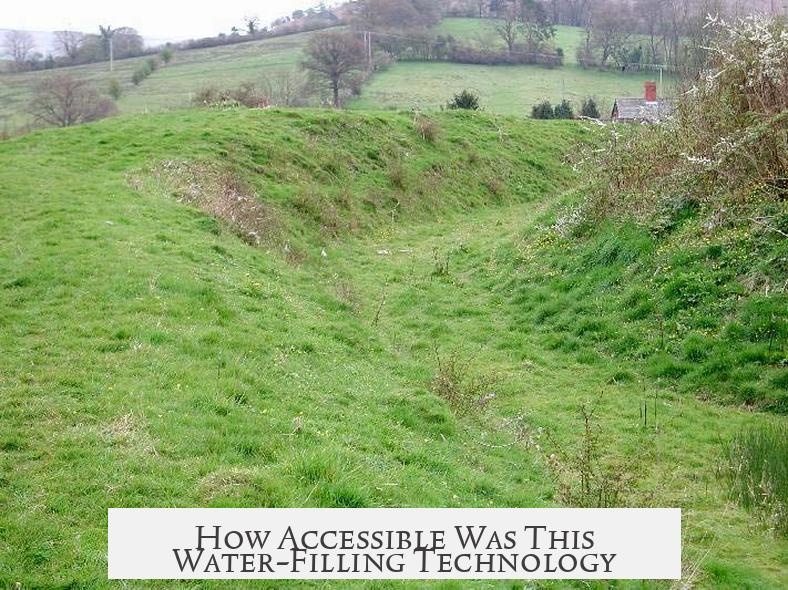

Medieval moats were filled depending on local conditions and available resources, with methods tailored to the type of moat and water access. Builders used simple but effective means to fill moats, balancing defense with the site’s natural features. Accessibility of these methods was generally high given existing medieval technology.

Two main types of moats existed: dry and watered. Dry moats lacked water, often found where water was scarce. Builders dug deep ditches with raised earth embankments from the excavated soil. These ditches served defensive purposes by creating obstacles. Sometimes, they doubled as rubbish dumps or latrines, adding further deterrents against attackers. In some cases, dry moats were filled with spikes or thorn bushes.

Watered moats required a reliable water source. Builders diverted local streams or dammed small waterways to channel water into the moat. They might also dig aqueduct-like channels connecting to natural lakes or fish ponds nearby. These ponds were multifunctional, often supporting castle inhabitants by breeding fish for food. This practical use reflected careful planning and landscape management.

Regarding accessibility, construction teams of the medieval period found moat-filling tasks feasible. Engineering knowledge on hydrological manipulation was well-established by this time. Techniques such as digging channels, building dams, and water diversion were common, used widely for mills, irrigation, and agriculture. The skill needed to transfer these methods to moat construction was within the capability of castle builders and laborers.

- Dry moats were simpler and sometimes left empty.

- Wet moats depended on nearby water sources and hydraulic work.

- Water management technology was well-developed in medieval Europe.

- Using moats as fish ponds added a practical food supply element.

- Castle builders had sufficient skills and tools to create functional moats.

How Were Moats Filled in the Medieval Period and How Accessible Were They for People Creating Castles?

Moats were filled through strategic water diversion and earthwork techniques, with medieval builders using nearby streams, lakes, and aqueducts to flood their defensive ditches. This process was quite accessible due to the long-standing knowledge of water management, making moats a key defensive and symbolic feature in castle construction.

Now, let’s dive deeper into this fascinating feat of medieval engineering. Picture the castle builders of old standing beside muddy trenches, plotting how to make their fortress tougher to storm. The moat was much more than a simple water-filled ditch—it was a barrier crafted with deliberate, well-planned engineering. But how did they fill these moats, and how easy was it to do so? Spoiler alert: It wasn’t magic, but close enough for the medieval mind.

Moats: More than Just a Water Trap

The primary purpose of moats was to slow and frustrate attackers. Imagine the chaos for an invading soldier trying to scale a castle wall, only to be greeted by a gaping watery trench or a deep dry ditch. Some moats completely surrounded the castle (classic full moats), while others, like those in Anglo-Norman manors, were three-sided. These 3-sided moats guided attackers toward heavily damaged zones, cleverly funneling foes into traps or well-defended points.

However, water wasn’t always a given. Builders sometimes had to innovate with dry moats—these were deep ditches without water, often filled with obstacles or used as rubbish dumps and even latrines. Gross? Yes, but effective at deterring enemy advances.

Dry or Watered? How Did They Decide?

The decision to fill moats with water depended largely on available water sources. If a castle sat near a river, lake, or stream, the builders could divert water into the moat. Otherwise, they resorted to dry moats. Here’s the science behind water filling: the builders dug channels—think aqueduct-like waterways—to funnel water from streams or lakes into the moat. They could also dam small streams to flood desired areas.

In many cases, these watery trenches doubled as fish ponds, providing not only protection but a food source for the castle’s inhabitants. Clever, right? A moat wasn’t just a defensive feature; it was part of the sustainable living system surrounding the castle.

How Accessible Was This Water-Filling Technology?

Unlike some might assume, filling moats with water was within the reach of many medieval builders. Humans had been manipulating water for agriculture and settlement purposes for centuries by this time. Building dykes, changing water flow, and constructing rudimentary aqueducts were skills known across Europe. The technology was simple—dig channels, block streams—and effective.

Even smaller lordships with less grand resources could build a moat, either dry or wet, depending on local geography. The labor-intensive aspects lay more in the digging than the water management itself. We’re talking about communal effort with shovels, wheelbarrows, and plenty of muscle.

The Evolution of Moats and Their Symbolic Power

Let’s fast forward a bit to the late 14th century. As warfare evolved, moats took on a new role. They became less crucial for defense and more about show. Landowners wanted to flaunt their status through ornamental moats. Those who could afford it invested in lavishly designed, water-filled moats that screamed, “I am important and powerful!”

During periods when landscaping became a high art—think Capability Brown-era gardens—the moats were either newly constructed or redesigned as part of grand estates. Water was carefully diverted and controlled not just for defense but for beauty and prestige.

Practical Tips and Examples for Medieval Moat Filling

- Start with local water sources: Builders scoped out nearby streams or lakes first.

- Dig strategic channels: Simple trenches or aqueducts brought water to the moat. Directing water required careful planning to avoid floods or drying out.

- Consider fish farming: Filling moats with fish boosted food supply.

- When water wasn’t an option: Build a dry moat with angled banks and obstacles for defense.

- Community effort: Moat building was labor-heavy but technologically straightforward.

For example, Windsor Castle, near the River Thames, had access to plenty of water and boasted a classic water moat. In contrast, many inland castles sported dry moats, proving that a lack of water didn’t mean giving up defense.

Final Thoughts: Did Everyone Get to Have a Moat?

In reality, accessibility varied by location and wealth. But the knowledge? That was widespread. People knew how to fill moats, but the presence of water and resources decided the final form.

Would you rather face a water-filled moat or a dry, spike-filled ditch? For an invader, neither sounds inviting. For a castle builder, knowing how to fill a moat was a vital skill tied to geography, labor, and ingenuity.

In the end, moats reflected much about medieval life: resourcefulness, defense, and status. Next time you see a castle picture with a shimmering moat, remember the hard work and smart water tricks that made it possible.