People in the Middle Ages bathed or cleansed themselves with varying frequency depending on their social status, geographical location, cultural background, and period within the Middle Ages. Bathing habits were notably different between royalty, the upper classes, and the lower classes, influenced by access to resources, beliefs about health, and social customs.

Among royalty and the upper classes, bathing had a defined role and was supported by available infrastructure. Royal residences such as Windsor Castle included baths with running water as early as the mid-13th century. King Henry III of England commissioned work in 1256 to channel water from a spring through various parts of the castle, ending in a bath near the king’s hall. Repairs to bathing conduits at Westminster also demonstrate that royal facilities provided heated bathwater, with attendants responsible for maintaining and preparing them. King John made regular payments for heating his bath, showing the importance placed on cleanliness.

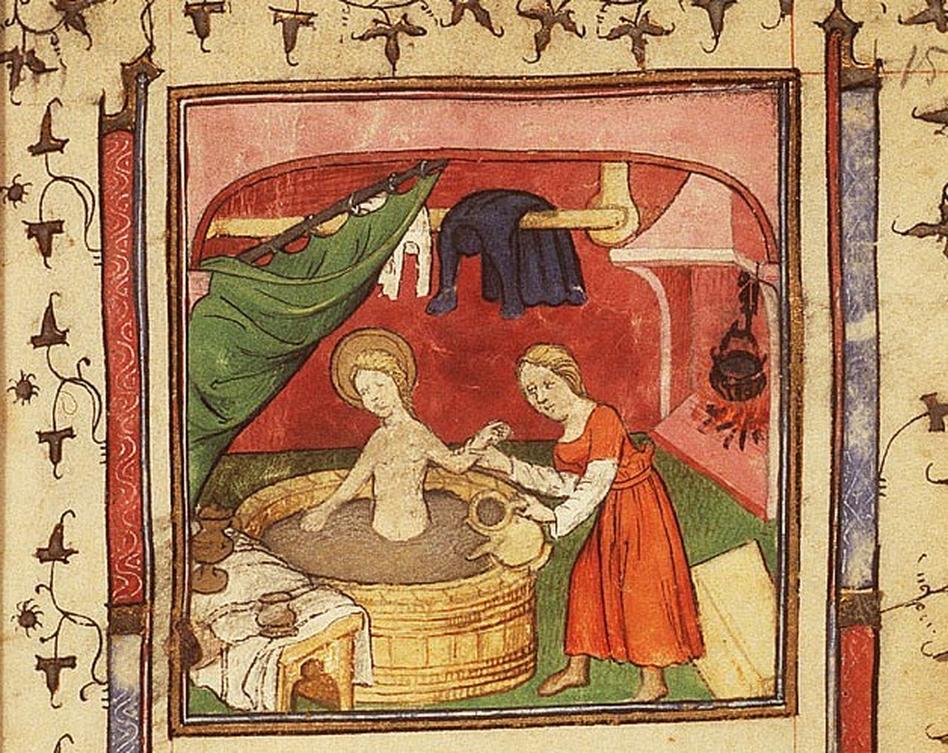

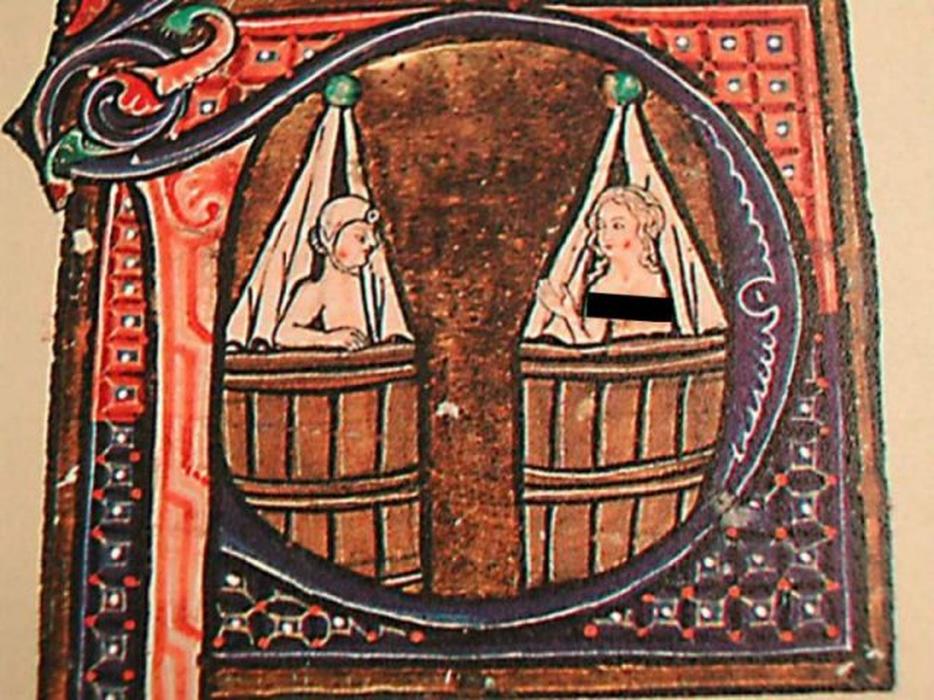

Members of the aristocracy typically bathed in tubs shaped like half-barrels, where water was poured in while the bather sat and washed. This process involved several servants to heat and carry water, implying significant effort and expense. Despite this, such full tub baths were taken only occasionally. However, daily washing was common among the upper class, usually at basins. Washing hands before and after meals was part of formal etiquette and service routines.

Over time, especially by the 16th century, bathing among the upper classes became much less frequent. Bathing was believed to risk health, supposedly weakening eyesight or spreading disease. Instead of regular baths, many nobility resorted to wearing potpourri or rubbing scented cloths on their bodies to mask odors. Even frequent face washing declined. King Louis XIV of France is famously reported to have bathed only twice in his lifetime. Nevertheless, upper class individuals would still bathe more often than the general population, though this might have been limited to a few times per year.

Among the lower classes, bathing was significantly less common. Because of both economic constraints and rising beliefs that bathing could transmit disease, many poor individuals may have bathed rarely or not at all. Hard evidence about their practices is scarce; much understanding comes from indirect sources and assumptions. Early medieval community pools existed, for instance in the 4th and 5th centuries, where bathing might occur monthly or so, but such communal facilities likely disappeared or declined during the high medieval period.

Specific cultural practices also influenced hygiene behaviors. For example, Scandinavians in the early medieval era reportedly washed at least once a week. This is reflected linguistically—Saturday in Icelandic, Laugardagur, means “washing day,” deriving from Old Norse. Norse sagas often mention regular hair-washing. Similarly, the Rus people in what is now Russia bathed fairly regularly, approximately once a month. These regional customs contrast with many Western European practices where infrequent bathing became common.

Archaeological discoveries support the importance placed on hygiene, especially among those who could afford tools for personal grooming. Common grave goods include nail clippers, combs, and ear spoons used for removing wax, indicating efforts to maintain cleanliness and appearance.

Attitudes toward bathing changed significantly due to religious and health concerns. The medieval Church increasingly restricted bathing, sometimes associating communal baths with immoral behavior. Meanwhile, the spread of diseases like the plague contributed to a belief that bathing opened the pores, allowing infection to enter the body. This combined pressure led to reduced bathing frequency.

It was not until the mid-18th century that Europeans broadly resumed more regular bathing habits. The long period of infrequent washing during the later Middle Ages reflected a mixture of cultural beliefs, technological limitations, and social structures.

| Social Group | Bathing Frequency | Bathing Method | Special Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Royalty | Occasionally with running water baths | Heated baths in dedicated facilities | Servants maintained water heating; formal bath rooms |

| Upper Class/Aristocracy | Occasional full baths; daily washing at basins | Tubs resembling half-barrels, basin washing | Daily hand washing before/after meals; scent use when not bathing |

| Lower Classes | Rarely bathed, possibly minimal washing | Occasional communal baths in early medieval times | Beliefs that bathing spread disease; lack of facilities |

- Medieval royalty had access to running water baths and attendants.

- Upper classes bathed infrequently but practiced daily hand washing at basins.

- Lower classes bathed rarely, if at all, due to cultural and economic limits.

- Scandinavians and some Eastern Europeans maintained more regular bathing habits.

- Religious views and disease fears reduced bathing frequency over time.

How Often Did People in the Middle Ages Bathe? Spoiler: It’s Not What You Expect!

So, how often did people in the Middle Ages actually bathe? Did royalty splash around more, or were peasants secretly cleaner than history suggests? Let’s dive into these murky waters and find out the truth, which might surprise you.

Contrary to popular belief, bathing habits varied quite a bit depending on social status, culture, and changing beliefs over time. Bathing was not just a simple hygiene routine but was woven into everyday life differently for kings, nobles, and common folks.

Royalty and the Upper Class: Bathing Was a Royal Affair

Let’s start with the top dogs—the kings, queens, and nobles. Far from being grimy, many of them actually cared deeply about cleanliness. For example, in 1256, King Henry III ordered extensive work at Windsor Castle to bring fresh spring water inside and even built baths near his halls. Just imagine the workers hauling water to fill these royal tubs—it was no small feat.

King John didn’t just dip his toes either; he paid servants specifically to heat his bathwater. Bathing wasn’t an everyday activity but definitely a part of the accepted upper-class routine.

Aristocrats typically bathed in tubs resembling half-barrels filled with water poured over them. This wasn’t like your quick shower; the process was laborious, requiring servants to heat and carry heated water. Still, daily washing—especially hand washing in basins—was common among the elite. Washing hands before and after meals was almost a ceremonial act, part of the dining etiquette.

However, bathing frequency decreased over time. By the 16th century, even the posh folks bathed sparingly—only a few times a year. Isn’t that shocking? People believed washing the face could weaken eyesight or cause disease. Royalty sometimes relied on potpourri or scented cloths to mask odors. For example, King Louis XIV reportedly bathed only twice in his entire life!

Lower Classes: Were Peasants Just … Smelly?

Now, what about the peasants and everyday folks? The stereotype says peasant = dirt bucket, but it’s not that simple.

Many lower-class people likely bathed less, especially as time went on and the Church placed more restrictions on bathing. Diseases such as the plague fueled fears that water might carry illnesses. So, many may have avoided baths altogether.

But they did wash—just not like the aristocrats. Some research hints that communal bathing was common in early medieval times, around the 4th and 5th centuries. People might bathe roughly once a month in community pools. But concrete evidence about everyday commoners’ rituals is thin, leaving some guesswork in play.

Did Culture Play a Role? Absolutely!

Bathing habits weren’t uniform across Europe. For example, Scandinavians took their hygiene seriously. Their word for Saturday is “Laugardagur” or washing-day—talk about dedication! Saga stories talk about hair washing, and Ibn Fadlan’s accounts of the Rus mention their regular bathing.

Similarly, Russians bathed about once a month or so, more routinely than their Western counterparts. This shows cultural values shaped how cleanliness was perceived and practiced.

Archaeological Clues: Hygiene Was Considered Important

It’s not all guesswork, though. Archaeologists have found plenty of personal hygiene tools in graves: nail clippers, combs, and even little ear spoons for wax removal. These finds point to personal grooming as a meaningful part of daily life across social classes.

Why Did Bathing Decline? The Church and Disease Fears

As time moved on, bathing became less frequent due to two main reasons: religious attitudes and health fears. The Church discouraged excessive bathing, sometimes viewing it as sinful or tempting. At the same time, the rise of plagues and other diseases led people to think water might invite sickness by opening pores.

This avoidance of bathing lingered for centuries, not really changing until the mid-18th century. So those clean royal baths and occasional peasant splashes were exceptions in a widespread trend of minimal bathing.

So What Can We Learn About Middle Age Hygiene?

- Royalty and nobles took care to bathe, using running water and tubs, but frequency was limited. Their washing rituals balanced health, etiquette, and practicality.

- The lower classes bathed far less, sometimes merely rinsing or not bathing at all— driven by access issues and beliefs about disease.

- Cultural differences mattered: Scandinavians and Russians were more regular bathers, contrasting with Western Europeans.

- Religious and medical views often discouraged bathing, creating centuries of reduced practice.

If you ever visit a medieval history museum or reenactment, think of the effort and social layers behind something as simple as a bath. Cleanliness was a luxury for many, and “smelly” was not always about laziness but a complicated mix of beliefs, logistics, and culture.

So next time you enjoy a shower, spare a thought for Henry III and his royal plumbers—because for them, getting a bath was a big deal. And for you, it’s just a matter of turning a tap!