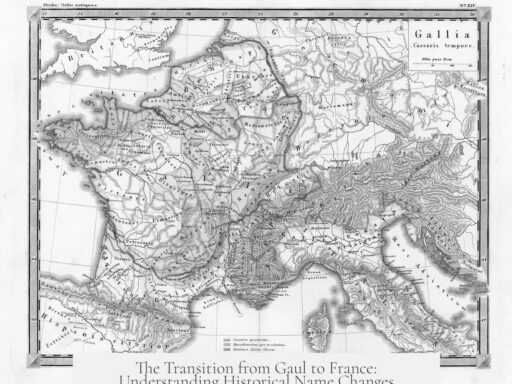

Salamanders, though amphibious animals, became associated with fire through a combination of natural observations, myth-making, and cultural reinterpretations over centuries. This association evolved from early Greek thought, through Roman naturalists, medieval scholars, and Renaissance folklore.

The earliest records date back to the 4th century BCE, when Theophrastus, a Greek philosopher, described salamanders as rain-predicting lizards. Early followers, like Theocritus and Nicander, ascribed magical properties to salamanders, linking them to love potions and malevolent spells. These mystical attributions blended two key ideas: salamanders’ amphibious nature and their seemingly magical qualities.

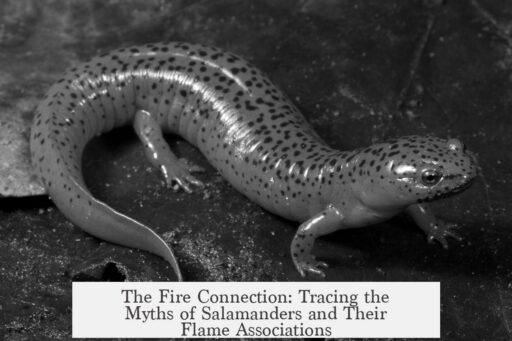

The species encountered by the Greeks were likely fire salamanders and alpine salamanders. These amphibians are active during rain and secrete toxic mucus, which can cause burning pain and muscle spasms. These defensive traits may have contributed to their mysterious reputation, blurring the boundaries between their aquatic lifestyle and powerful, fiery effects on predators.

By the 1st century CE, Pliny the Elder became a pivotal figure in the salamander-fire myth. In his writings, Pliny described reports that salamanders could extinguish fires due to their cold nature. While Pliny expressed some doubt, his writings spread widely and heavily influenced later thought. He also exaggerated salamanders’ toxicity, claiming drinking water contaminated by a salamander would be deadly. This emphasized their mythical status and linked them closely with extreme elements like fire and poison.

Alongside textual records, visual art reinforced salamanders’ link to fiery crafts. Archaeologists uncovered a bas-relief in Pompeii showing a fire salamander depicted on an anvil and forge. This imagery suggested salamanders’ association with blacksmithing and fire. Early commentators like Aelian noted salamanders were drawn to fires because they are cold, and could smother flames. This idea of fire-quenching salamanders persisted for centuries, blending natural coldness with supernatural fire control.

A fundamental shift in the myth occurred in the 5th century CE with Augustine of Hippo’s writings. He inverted the earlier idea that salamanders extinguished fire, instead claiming they lived inside flames unharmed. Augustine referenced naturalists when asserting salamanders survive in Sicilian volcanic fires without being consumed. This marked a crucial transformation from salamanders as fire suppressors to creatures embodying fire itself.

This new concept took firm hold during the Renaissance. Artists and writers popularized the imagery of salamanders emerging from flames and fireplaces. These stories were supported by salamanders’ actual behavior of hibernating in rotting logs, which when burned, seemed to release the animals suddenly. This fueled the belief in salamanders’ immunity to fire and their fiery origins. Renaissance culture enhanced the myth, solidifying salamanders as elemental fire beings in popular imagination.

To illustrate the evolution:

| Period | Key Idea | Source/Influence |

|---|---|---|

| 4th century BCE | Salamanders linked to water, rain, and magic potions | Theophrastus, Theocritus, Nicander |

| 1st century CE | Salamanders can extinguish fires; very toxic | Pliny the Elder |

| Roman era | Association with blacksmith forge, drawn to fire to quench it | Bas-reliefs at Pompeii; Aelian |

| 5th century CE | Salamanders live inside fire, unharmed | Augustine of Hippo |

| Renaissance | Popular fire-dwelling salamander folklore | Art, literature, communal anecdotes |

In summary, salamanders became associated with fire despite their amphibious nature primarily because of their natural behavior, toxic secretions, and brief appearances during rainy or smoky conditions. Misinterpretations and mystical embellishments expanded these observations into legends of salamanders living in or extinguishing flames. Influential writers and artists shaped and spread these ideas, transforming salamanders into symbols of fire in Western tradition.

- Early Greeks linked salamanders to water and magic due to their amphibious habits and toxic mucus.

- Roman naturalists like Pliny claimed salamanders extinguished fire, spreading this belief widely.

- Visual associations with blacksmithing connected salamanders to heated environments.

- Augustine of Hippo’s writings marked the shift to salamanders living within fire itself.

- Renaissance culture popularized the fiery salamander myth through art and story.

How Did Salamanders, Amphibious Creatures, Get Associated with Fire?

Salamanders didn’t just stroll into fiery legend by accident. Their real-life traits, cultural stories, and mistaken interpretations over centuries wove a tale making them the iconic “fire creatures” of myth. Let’s unravel this smoky mystery step-by-step, blending nature, history, and human imagination.

Why do we link salamanders—simple amphibians—with fire, a force that seems their enemy? It’s curious because salamanders are water-loving, cold-blooded creatures, yet history and myth entwine them tightly with flames.

From Natural Observation to Mystical Beginnings

It all begins in ancient Greece. Theophrastus, Aristotle’s second-in-command, first described salamanders around the 4th century BCE. He identified them as lizard-like animals whose presence predicted rain. So, salamanders were linked closely with water early on.

But the Greeks didn’t stop at rain prediction. In later centuries, figures such as Theocritus and Nicander attributed magical powers to salamanders. These little amphibians became ingredients in love potions and even “sorcerers’ lizards,” used in dark magic.

This early Greek lore combines two key ideas: salamanders are water-associated amphibians (active during rain) and mysterious creatures believed to possess magical qualities. These elements planted the mythological seeds.

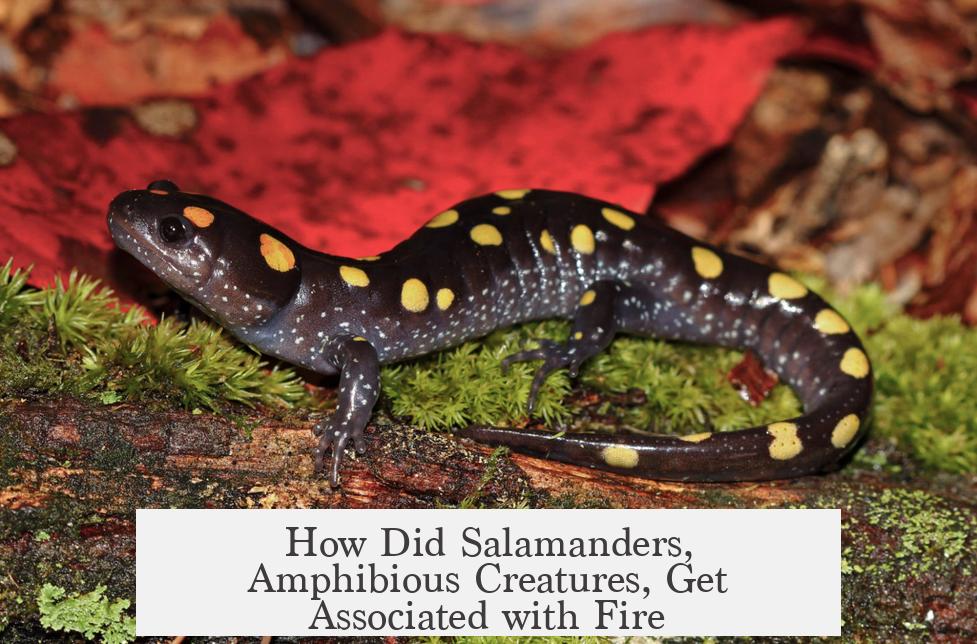

Real Salamanders’ Biology Fuels the Fire Myth

Here’s where biology sneaks in. The Greeks likely encountered fire salamanders and alpine salamanders. Both are amphibious and often active during wet weather.

Crucially, these salamanders secrete toxic mucus. This mucus causes a burning sensation and muscle cramps when touched, a natural defense that could easily be misunderstood.

Imagine a small amphibian that appears with rain, feels cold and slippery, and when grabbed “burns” your skin. That’s a fascinating riddle for ancient observers. The relationship between wetness and burning sensations creates a confusing but potent symbol—an amphibian mingling elements of water and fire.

Pliny the Elder: The Fire-Extinguishing Salamander

Step forward to the Roman era. Pliny the Elder, the authoritative naturalist who wrote in the 1st century CE, introduced the salamander’s fire lore to a wider audience. According to him, salamanders were so cold that if thrown into a fire, they would put it out.

Pliny was skeptical but reported this story nonetheless — and this became an important early record linking salamanders to fire. Plus, he exaggerated their toxicity, warning that drinking water touched by salamanders could be deadly. Talk about scaring off a curious amphibian!

This sophomore science-meets-folklore moment set a precedent: salamanders became known as magical creatures linked with fire control, specifically with the ability to quench flames due to their “coldness.”

From Blacksmiths’ Anvils to Fire Myth Symbolism

The connection deepened. Archaeologists found a bas-relief in Pompeii depicting a fire salamander straddling a blacksmith’s anvil and forge. During the early centuries CE, written sources like Aelian claimed salamanders, cold and yearning for warmth, would slink toward fires but actually put them out.

Here, salamanders symbolized beings in fire-related environments—not as fire starters but as natural fire extinguishers. This symbolism fit well with blacksmiths who worked with fire constantly, adding cultural flavor to the salamander’s mystique.

Augustine’s Twist: From Fire-Quenchers to Fire-Dwellers

Now the plot thickens. Around the 5th century CE, Augustine of Hippo shifts the story dramatically in his influential work City of God. Augustine says salamanders “live in fire,” citing mountains in Sicily that burn endlessly but remain unharmed.

This marks a reversal—from the salamander being a cool creature that puts out fire to a mystical animal that thrives in flame. Augustine’s statement reflects a reinterpretation and mythological amplification, drawing from earlier sources but flipping the narrative.

At this point, salamanders stop being just amphibians with strange mucus and become almost mythical fire spirits, immune to harm and born from the flickering flames themselves.

The Renaissance: Myth and Art Cement the Association

The story doesn’t stop in medieval times; it flourishes in the Renaissance. Art and literature of the period show salamanders scrambling from fireplaces, as if born directly from fire. This folklore aligns with a real salamander behavior: hibernating inside rotting logs, which sometimes burn unexpectedly.

This natural behavior likely fed tales of salamanders either surviving fire unscathed or emerging from it, strengthening the myth that salamanders possess fiery immunity or are even creatures of flame.

The Renaissance fascination with salamanders as fire beings entrenches this myth firmly in European culture, making it a classic example of how nature, observation, and human imagination weave powerful folklore.

So, Why the Fire Connection?

- Biology paired with mystique: Salamanders are amphibious but secrete burning mucus, confusing early observers.

- Cold creatures in fire: Their natural “frigidity” suggested fire-quenching ability.

- Symbolism in craft: Associated with blacksmith fire and coldness together.

- Misinterpretations over time: Augustinian writings shifted from salamanders quenching fire to living in it.

- Folklore reinforcement: Renaissance anecdotes about salamanders in burning wood cement the myth.

In other words, salamanders’ amphibious nature, mysterious mucus, cultural stories, and hibernation habits combined into a legendary identity far beyond their humble biology.

What Can We Learn From This?

Stories evolve. Even the simplest creatures become vessels for human imagination. Often, myths grow from a mix of fact and misunderstanding, fueled by cultural needs or artistic expression.

Salamanders remind us to look carefully at nature and question how myths develop over time. Can you imagine what modern myths might arise from today’s little-known animals—maybe a frog that glows in the dark suddenly becomes a symbol of magic or mystery?

For educators and storytellers, the salamander’s fiery myth offers rich lessons: observe carefully, seek evidence, but appreciate the power of narrative as it shapes culture.

Practical Salamander Tidbit

If you’re ever near a salamander during a rainy walk, remember these fascinating creatures are more closely related to water than fire. Touch with care—their mucus can cause irritation. And if you see one near a campfire, don’t worry; it’s not dancing with the flames. It’s just a little amphibian caught up in a centuries-old story.

Final Thought

How does a moist, shy amphibian become a legendary fire dweller? Through biology’s quirks, ancient lore, writers’ reinterpretations, and human imagination. Salamanders, in their mysterious way, offer a fiery example of how facts and fables intertwine to create lasting myths.