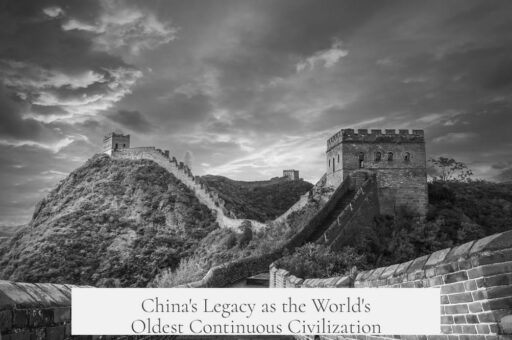

China earns the title of the “world’s oldest continuous civilisation” through its lengthy and largely uninterrupted cultural, political, and social history, which spans thousands of years with a consistent identity that has evolved but retained core elements.

China’s civilisation traces back to the Yellow River Basin around 3000 BCE, where early Stone Age communities laid the foundation for later complex societies. Written history begins roughly 3,500 years ago with the Shang dynasty, followed by the Zhou and subsequent dynasties. This long written record underpins the claim to continuity.

The idea of a 5,000-year civilization is a powerful narrative shaped during the 20th century, influenced by cultural and political currents rather than fixed historical evidence. Scholarly debate has contested how far back China’s continuous history extends. Early Confucian and Neo-Confucian thought upheld the validity of traditional accounts of Xia and Shang dynasties, despite scarce direct evidence.

In contrast, the Doubting Antiquity School, emerging from the 1910s’ New Culture Movement, challenged these narratives as politically motivated fabrications. More recently, archaeological discoveries have revived support for traditional texts, promoting a “Believing Antiquity” perspective that affirms much of early Chinese historiography as reliable.

China’s continuity is complex and not without interruptions. Several periods of political fragmentation, such as the Warring States or times when non-Han peoples ruled parts of China, challenge the notion of unbroken statehood. Dynasties rose and fell in cycles of prosperity and decline, influenced by conquest and internal strife.

For instance, the Qing dynasty, founded by the Manchus in 1636, ruled until 1912, illustrating how non-Han rulers became integrated into the civilization without breaking its continuity. The process of assimilation transformed such conquerors culturally, reinforcing the civilizational identity rather than dissolving it.

Some alternative theories, like the early Sino-Babylonian hypothesis, posited an external origin for Chinese civilisation aiming to link it to Mesopotamia. Such ideas gained temporary traction but were discredited by later archaeological evidence confirming an indigenous development along the Yellow River.

The notion of continuity generally focuses on Han Chinese culture, often sidelining the diverse histories of other ethnic groups and regions within present-day China. While the PRC encompasses many peoples, the dominant historical narrative emphasizes a core Han civilization spanning millennia.

Despite enormous upheavals, including the Cultural Revolution, which sought to sever ties with the past by destroying relics and challenging tradition, Chinese cultural heritage survived. Since that period, there has been renewed emphasis on celebrating China’s long history as a source of national pride and identity.

The civilisation’s advancement in technology, agriculture, governance, literature, and philosophy throughout its long history also reinforces its claim. Inventions like paper, gunpowder, the compass, silk, tea, and sophisticated irrigation practices highlight China’s deep and enduring contributions to human progress.

| Aspect | Details Supporting Continuity |

|---|---|

| Origin | Yellow River Basin settlements circa 3000 BCE; early dynasties (Xia, Shang, Zhou) |

| Written Record | Continuous written history for 3,500+ years |

| Cultural Assimilation | Foreign rulers assimilated (e.g., Manchus), sustaining cultural identity |

| Archaeological Evidence | Supports historical narratives, reinforcing “Believing Antiquity” view |

| Political Changes | Intermittent dynastic interruptions but overarching civilizational identity persists |

| Technological-Cultural Impact | Numerous inventions and art highlight continuous innovation |

In summary, while the claim that China is the world’s oldest continuous civilisation faces scholarly debate due to political and historical complexities, it is generally supported by a continuous cultural tradition spanning several millennia, robust written records, and persistent social values.

- The “5000 years” narrative is shaped by cultural pride and political factors, not a strict historical consensus.

- Archaeology increasingly supports traditional histories from early periods.

- Dynastic cycles include foreign rulers assimilated into the civilizational framework.

- Continuity emphasizes Han culture and core regions, often excluding other ethnic histories.

- Modern political upheavals challenged historical continuity but ultimately reinforced interest in it.

- Technological and cultural achievements illustrate long-term development sustaining civilisation.

What does “5000 years of history” mean in the context of China?

It refers to a widely accepted idea that China’s civilization spans roughly five millennia. However, this concept has evolved over time and is influenced by cultural and political views rather than fixed historical fact.

How do scholars view the early history of China before the Eastern Zhou period?

Some believe records of early dynasties like Xia and Shang have truth behind them, while others argue these accounts were altered for political reasons. Recent archaeological findings support some traditional texts but debates continue.

Why is China called the “world’s oldest continuous civilisation” despite historical disruptions?

Though there were periods of political division and changes in ruling powers, the core cultural traditions and identity linked to Han Chinese have persisted over time, which supports the claim of continuity.

How do ethnic and regional histories affect the narrative of Chinese continuity?

The 5000-year history mostly centers on Han Chinese culture. Other ethnic groups within China have distinct histories that may not align with this narrative, showing greater complexity in the region’s past.

What role did 20th-century movements play in shaping China’s historical narrative?

The Cultural Revolution aimed to break from the past by destroying relics. Later, there was a strong effort to reclaim and emphasize China’s long history as a response to that period’s disruptions.