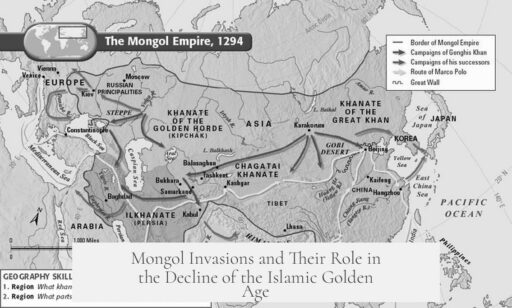

The Mongol invasions were pivotal in ending the Islamic Golden Age within the Arab Middle East, especially by destroying Baghdad and Damascus, but they did not end Islamic civilization or intellectual progress globally. Instead, they shifted Muslim power centers westward and spurred Islam’s spread beyond the Middle East.

Before the Mongols arrived, the Abbasid Caliphate’s lands were fragmented. Various governors controlled regions with limited central authority confined to Baghdad. Despite this political division, the Muslim world remained affluent, maintaining thriving cities and vast libraries. Baghdad still served as a vibrant cultural and intellectual hub.

When the Mongols swept through the region in the early 13th century, they unleashed unprecedented violence. Baghdad, one of the largest cities in the Middle East, suffered a catastrophic massacre. Its famed libraries were destroyed; legends say the Tigris River ran black from the ink of thrown books. This destruction erased centuries of accumulated knowledge.

Beyond physical destruction, the Mongols caused dramatic demographic shifts. The population of key areas like Syria and Iraq plummeted. Many survivors migrated west toward the Hejaz, Egypt, and Anatolia, causing the Levant and Mesopotamia to become depopulated and war-torn for decades. Recovery was slow, with some estimates suggesting the population did not rebound to pre-invasion levels until the 20th century.

As a result, the traditional centers of Arab Muslim power, notably Baghdad and Damascus, lost their dominance. Muslim political and cultural leadership transitioned to Cairo, Córdoba, and later Constantinople. These cities thrived independently of the former Arab heartlands.

| Aspect | Impact of Mongol Invasions |

|---|---|

| Political Control | Collapse of Abbasid central authority; rise of new power centers in Cairo and Anatolia |

| Population | Killed or displaced; Levant and Iraq severely depopulated for centuries |

| Cultural Centers | Destruction of libraries and urban centers diminished intellectual activity locally |

| Geographical Shift | Spread of Islamic influence into non-Arab areas of Asia and Africa accelerated |

| Long-Term Effects | Regional stagnation in Arab lands; Islam expanded and evolved in other regions |

It is important to view this transformation as a watershed moment specific to the Middle East, rather than a terminal decline of Islamic civilization. The so-called “Islamic Golden Age” is often framed as primarily Arab and centered in the Middle East. This misses the broader reality of Islam’s global reach, from Iberia in the west to East Asia in the east.

In fact, after 1300, Muslim powers outside the Arab world flourished independently of the Mongols. The Delhi Sultanate in India, Muslim states in Southeast Asia such as Aceh, and the Mamluks in Egypt expanded their cultural and political influence.

The Mongols themselves, once converted in parts, became patrons of arts, architecture, and science. They facilitated cultural exchanges between West Asia and China, encouraging the production of important works and innovations in governance. The Ilkhanate sponsored remarkable architectural achievements and literature. This patronage contributed to the ongoing evolution of Islamic culture beyond the destruction in Baghdad.

According to scholar Richard Bulliet, Islam’s most rapid expansion took place after 1300, largely outside the former Arab heartlands. Today, much of the world’s Muslim population descends from post-1300 conversions in Asia and Africa. Mongol rule indirectly helped this process by shifting the focus of Muslim civilization geographically and culturally.

Overall, the Mongol invasions ended the Abbasid Caliphate’s political and cultural domination. They caused a centuries-long stagnation and rupture in the Arab Middle East’s intellectual output. However, they did not extinguish Islamic civilization as a whole. Islam adapted and spread in new directions. Muslim power shifted to other regions where cultural and political growth continued unabated.

- Mongol invasions destroyed Baghdad and depopulated key Arab regions, ending their dominance.

- Islamic Golden Age as centered in Baghdad ended, but Islamic civilization persisted elsewhere.

- New Muslim power centers emerged in Cairo, Delhi, and Anatolia, preserving cultural vitality.

- Mongols helped spread Islam and encouraged cultural exchanges across Eurasia.

- Population recovery in Syria and Iraq delayed for centuries, contributing to regional stagnation.

How Important Were the Mongol Invasions to the Ending of the Islamic Golden Age?

To cut to the chase, the Mongol invasions were hugely important in ending the Islamic Golden Age as a political and cultural era centered in Baghdad and the Levant, but they did not end Islamic civilization or intellectual progress as a whole. The story is nuanced and deserves a closer look.

By the early 13th century, the heart of the Islamic Golden Age—the Abbasid Caliphate centered in Baghdad—was already showing cracks. Imagine a realm where the rulers are like feuding feudal lords, squabbling governors carving out their own territories, and the Caliph basically stuck in his palace like a royal recluse. This political fragmentation left Abbasid lands vulnerable.

Still, Baghdad remains a jewel of the Islamic world. It bustled with wealth, vibrant society, and giant libraries holding centuries of knowledge. This wasn’t a civilization on life support; it was alive, intellectually rich, and functioning.

The Mongol Invasion: When the Storm Hit

Enter the Mongols, the 13th-century version of a barbarian whirlwind—only with better horses and more archery skills. Their sack of Baghdad in 1258 was catastrophic. The city’s population suffered a massive massacre. The cherished libraries, especially, faced a tragic fate. Legend has it that the waters of the Tigris ran black due to the ink from the destroyed books thrown into the river. These losses weren’t just physical—they were cultural and intellectual catastrophes.

But the destruction went far beyond Baghdad’s libraries. The invasion emptied large parts of Iraq and Syria as populations fled, leading to a mass westward migration toward Egypt, the Hejaz, and western Anatolia. These once-powerful centers, including Damascus, were left shattered. For centuries, these regions remained war-torn wastelands, unable to recover their former glory. In fact, estimates suggest the population of Iraq and Syria only bounced back to pre-Mongol levels by the 1900s. That’s 700 years of lost potential, innovation, and prosperity.

Shifting Sands: The Changing Power Landscape of Islam

So did the Mongol invasions signal the absolute end of Islamic civilization? No. It meant a dramatic shift in power and culture away from the Arab heartlands to other Muslim regions. Cairo, Cordoba, and later Constantinople took on more prominent roles. Great Muslim powers flourished in places untouched by the Mongols, such as the Delhi Sultanate, Egypt, and parts of North Africa.

Interestingly, the Mongols themselves were not just destroyers. Over time, several Mongol factions embraced Islam. Under Ilkhanid rule, the Mongol leaders became patrons of arts and science. Schools of thought flourished once again. The famous Persian masterpiece, the Shahnameh, was completed under their patronage. Architecture blossomed, with stunning examples like the city of Sultaniyya. Innovations in governance also emerged during Mongol rule. This complex relationship challenges the simplistic narrative that Mongol invasions were purely catastrophic.

What About the “Islamic Golden Age” Label?

The term “Golden Age” is often used, but it’s a slippery label. It tends to gloss over regional differences and gives an Arab-centric view of Islamic history. Islam by the 13th century stretched from Iberia to East Asia, a vast, diverse world. The end of Baghdad’s prominence is not the end of Islamic cultural or intellectual vitality across this huge geography. For instance, post-Mongol, Islam spread rapidly in regions like South and Southeast Asia—where many Muslims today trace their lineage to conversions after 1300 CE.

Indeed, scholar Dr. Richard Bulliet highlights that this period was one of expansion rather than decline globally. The Mongols created more cultural exchange, particularly between Islamic centers and Yuan China, opening new trade routes and ideas.

Why Should We Care About This Moment?

This moment is a classic example of history’s complexity. It’s easy to say an event “ended” an era, but reality is multifaceted. The Mongol invasions destroyed Baghdad’s dominance and fragmented the political unity of the Muslim world’s heartland, but they also acted as catalysts for broader cultural shifts and expansions elsewhere.

If you think about it, the Mongols’ impact resembles a massive earthquake—not just destruction but reshaping landscapes. Through chaos came new centers of power and cross-cultural interactions that might never have happened otherwise.

What Can We Learn? Practical Insights

- Center of Influence Can Shift: Dominant cultural or political centers can collapse or decline, but the broader civilization might adapt, survive, and even thrive elsewhere. In today’s globalized world, this reminds us to expect change and be ready for new hubs to emerge.

- Destruction Doesn’t Mean Total Loss: Though Baghdad’s libraries were destroyed, knowledge wasn’t lost forever. Manuscripts survived elsewhere. Other Islamic capitals carried the torch of science, art, and philosophy.

- Barbarian ≠ Destroyer Only: The Mongols were often painted just as ruthless destroyers. The reality is more nuanced. They became arts patrons, administrators, and even Islamic converts. Perspectives can shift with time and nuance.

In conclusion, the Mongol invasions of the 13th century were critically important to ending the Islamic Golden Age in Baghdad and its surroundings. They brutally ended one chapter, causing population losses, stagnation, and ruin. Yet, they also ushered in new chapters beyond the Arab world, spreading Islam faster than before, enhancing cultural exchanges, and changing global Islam’s geography.

“The end of a golden age is not the end of civilization.” The Mongol invasions prove this well.

References: New Cambridge History of Islam (2010), Richard Bulliet’s lectures on the History of Iran.