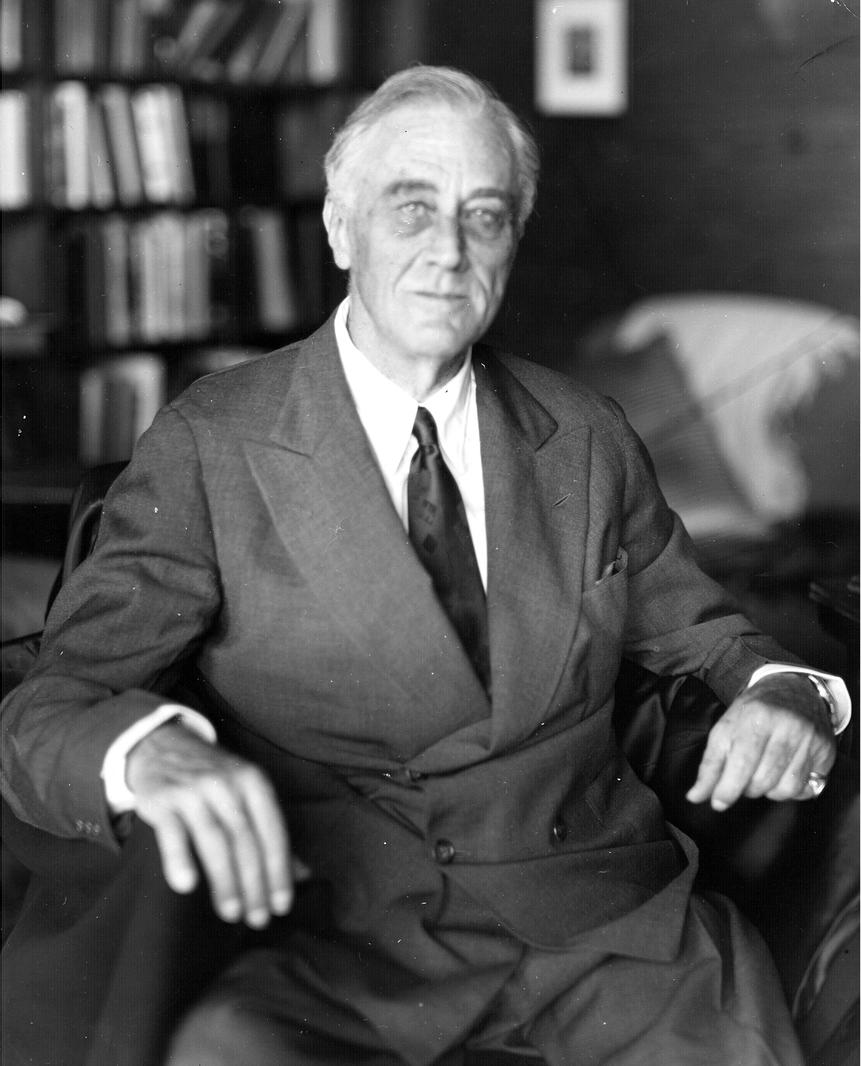

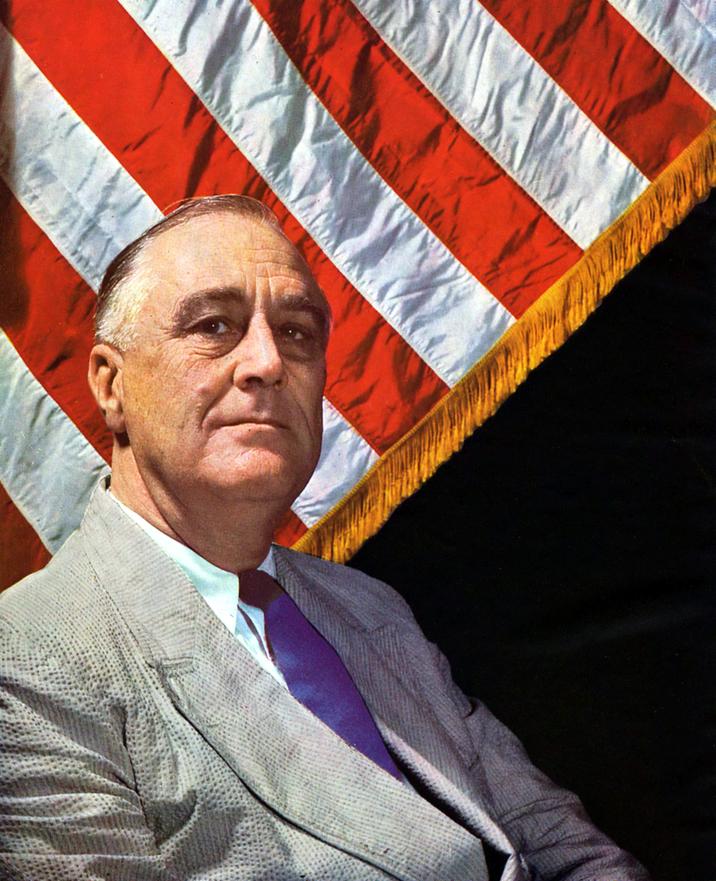

Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill shared a complex relationship defined by mutual respect and strategic necessity rather than pure friendship. Their alliance was rooted in cultural ties and personal similarities, but marked by fundamental political and ideological differences that shaped their wartime cooperation and post-war visions.

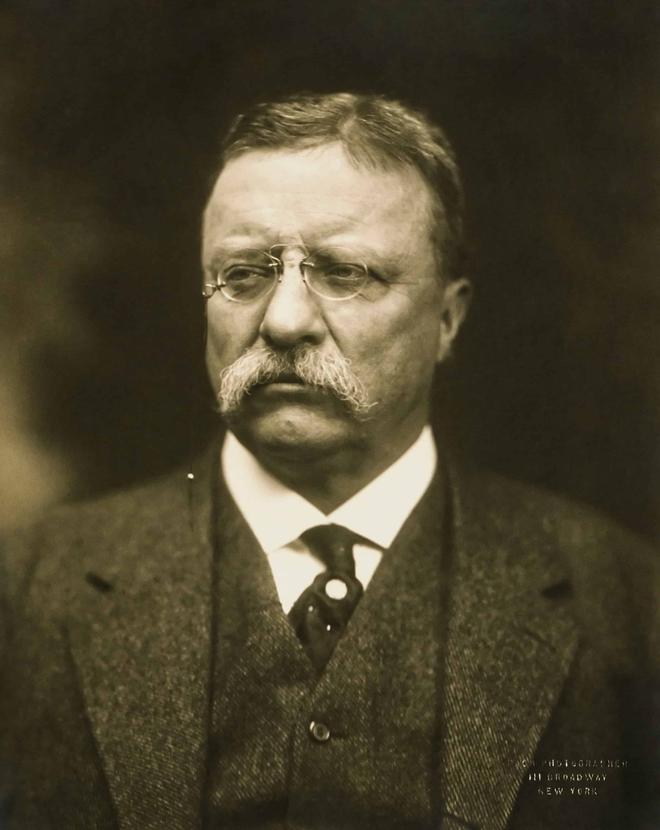

The foundation of their interaction stemmed from the intertwined histories, language, and culture between the United States and Britain. Both men hailed from prominent, aristocratic families, grounding their bond in shared social backgrounds. Churchill came from the British nobility, belonging to the powerful Spencer-Churchill family, while Roosevelt descended from Dutch-American nobility entrenched in New York’s Hudson Valley. Their upper-class lineage gave them much common ground personally and culturally, including a mutual disdain for traditional academia and a shared struggle with periods of depression. This background created an informal understanding: their countries generally supported each other’s international policies.

Despite this cultural kinship, their beliefs diverged sharply, particularly regarding empire and governance. Churchill epitomized British aristocracy, embracing imperialism and the maintenance of the British Empire as integral to his nation’s identity. Roosevelt, conversely, embodied American puritan-style public service, motivated by Christian duty and a vision that emphasized democratic ideals and social reform. Though both accepted the concept of noblesse oblige, their interpretations differed—Churchill saw it as maintaining imperial responsibilities, Roosevelt as fostering equitable governance and eventual decolonization.

This contrast extended to national philosophies. American exceptionalism rose strongly by the end of World War I, leading the U.S. to reject colonial empire as incompatible with its founding principles. While Britain clung to imperial rule, the U.S. was increasingly uncomfortable with colonization, reflected in policy trends after the Spanish-American War. Churchill regarded empire as essential to British identity, whereas Roosevelt viewed it as a relic to be dismantled for a new post-war order.

During World War II, this divergence created friction beneath their allied front. Roosevelt sympathized deeply with Britain’s struggle but operated under legal constraints like the Neutrality Act, which limited direct U.S. involvement early on. The Lend-Lease program emerged as a pragmatic solution, allowing the U.S. to support Britain with resources without breaching neutrality. Despite this cooperation, Roosevelt’s frustration with Churchill’s refusal to consider decolonization was palpable. He saw British imperial ambitions as incompatible with the emerging world order, increasingly skeptical of Churchill’s ideals steeped in traditional chivalry and empire.

Complicating their dynamic further was Roosevelt’s ideological proximity to Joseph Stalin. Roosevelt admired Stalin’s rejection of open imperialism, however flawed, contrasting with Churchill’s imperialist stance. This alignment sometimes led Roosevelt and Stalin to mock Churchill’s old-world honor codes. Meanwhile, within the American elite, figures like Harry Dexter White displayed growing sympathies for communism and the Soviet future, reflecting internal shifts in U.S. perspectives toward the USSR and global governance.

These ideological divides did not sever their alliance, but they did create an uneasy partnership—a “special relationship” marked by both cooperation and disagreement. Roosevelt’s push for decolonization made him an uncomfortable ally to Churchill, for whom British power was inseparable from empire. Churchill viewed Roosevelt’s demands as a form of national self-destruction for the United Kingdom, intensifying tensions between them. Their relationship was thus entwined: a partnership required by global conflict, yet resembling an unhappy marriage strained by incompatible worldviews.

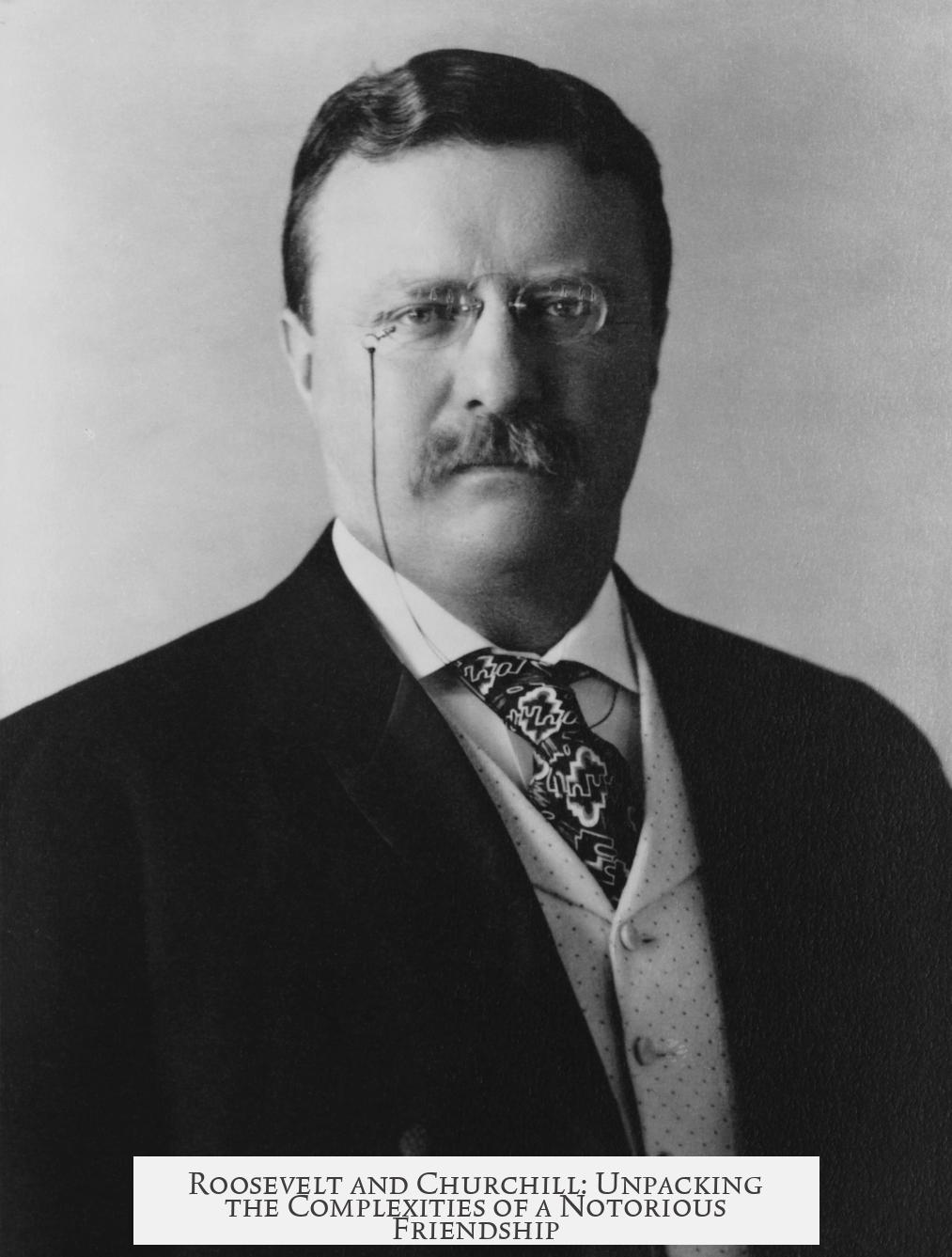

| Aspect | Churchill | Roosevelt |

|---|---|---|

| Background | British aristocracy (Spencer-Churchill family) | American nobility (Dutch Knickerbocker family) |

| Philosophy on Empire | Imperialist, defender of British colonial rule | Opposed empire, promoted decolonization |

| Political Alignment | Traditional monarchy-supporting conservative | Democratic idealist with progressive elements |

| World Order Vision | Preserve empire as a power source | Construct new order based on equality and decolonization |

| Relationship Nature | Respectful alliance but frustrated by Roosevelt’s policies | Admired Churchill but found imperialist ideas outdated |

Their relationship exemplifies the complexity of international alliances shaped by personal respect amid political discord. Both men stood as giants of their countries and eras, navigating immense pressures during one of history’s most tumultuous periods. Their rapport combined admiration with tension, cooperation with dissent.

- Roosevelt and Churchill shared cultural roots and personal similarities that facilitated their alliance.

- They differed significantly on imperialism: Churchill upheld the British Empire; Roosevelt favored decolonization.

- World War II required collaboration despite these ideological tensions.

- Roosevelt’s legal and political limits shaped initial U.S. support to Britain.

- Their “special relationship” was more a pragmatic partnership than an intimate friendship.

- Post-war visions highlighted their fundamental divides on empire and global order.

How Friendly Were Roosevelt and Churchill Really?

Answer first: Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill shared a complex and deeply significant relationship. They were allies bound by common culture and mutual goals, but their friendship was peppered with tension, fundamental disagreements, and a good dose of political theater. Let’s dig into how this dynamic really played out.

When you think about Roosevelt and Churchill, the iconic images of two leaders consulting over war strategy might make them seem like fast friends. But like any real relationship, theirs was layered and sometimes uneasy. What made their connection tick, and where did the friction lie?

1. Foundations of the Relationship: Common Ground and Aristocratic Roots

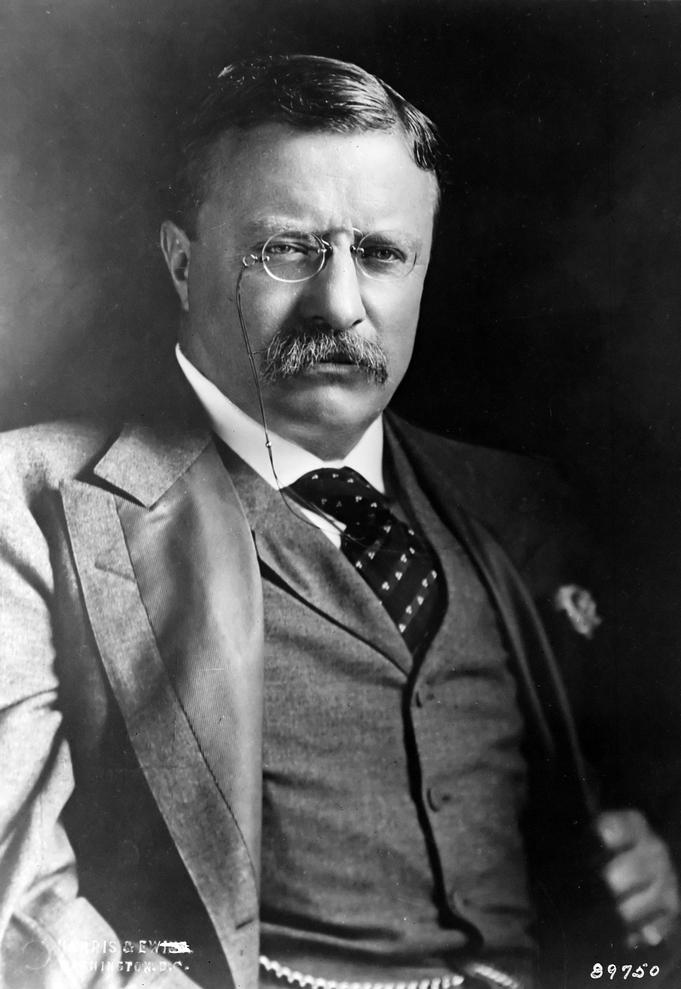

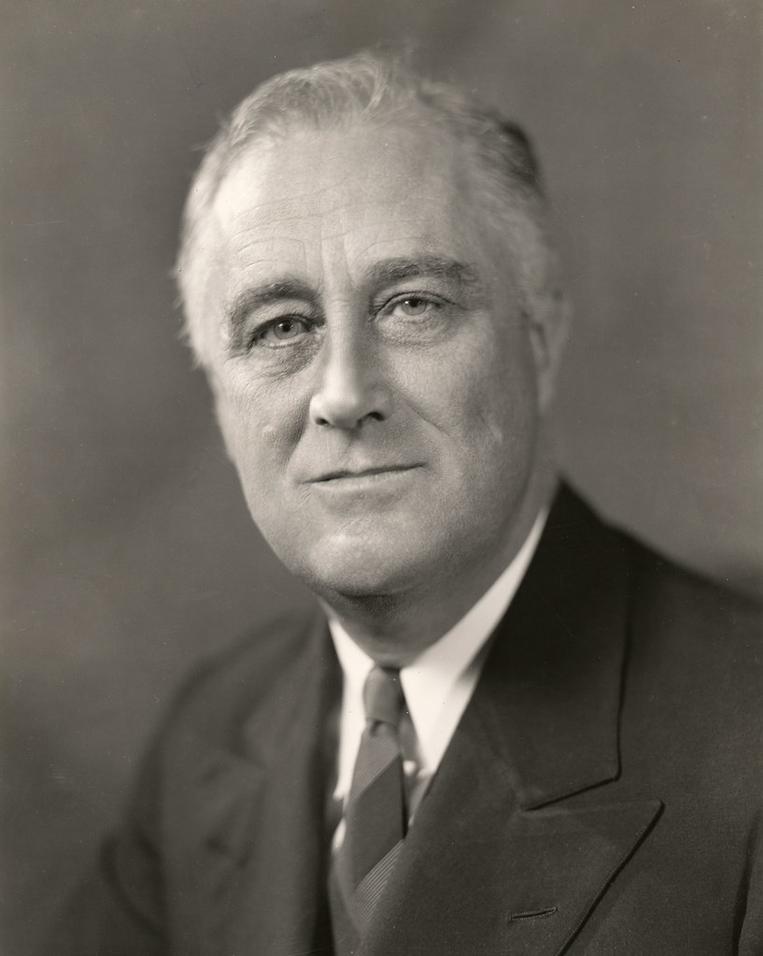

The roots of their connection start with a shared cultural background. Both hailed from elite families steeped in history and tradition. Churchill, with the formal name Spencer-Churchill, came from a powerful British aristocratic lineage. Think centuries of ruling men and landowners, serving an empire.

Roosevelt, on the other hand, was a product of American aristocracy, described as a knickerbocker—a noble Dutch family that controlled estates in New York’s Hudson Valley as if they were mini-kingdoms. So, while different, both had a strong sense of heritage and belonged to ruling classes.

They also clicked on a personal level. Both disliked the stifling academic world despite their elite educations and battled depression, a touch of shared humanity amid privilege.

2. Divergent Beliefs Beneath the Surface

However, this common ground didn’t erase their differences. Churchill was a staunch imperialist. He believed fervently in the British Empire’s global role, confident in aristocratic hierarchies and British superiority—the “old world” mindset at its finest.

Roosevelt, however, embodied a very different type of aristocracy. America’s elite leaned on puritan values and a Christian sense of duty to improve society. *Noblesse oblige*? Yes, but with a twist—serve the public good rather than dominate an empire.

And then there was ideology: Churchill stood for empire; Roosevelt leaned toward American exceptionalism, uncomfortable with colonialism. He’d watched his country step away from colonial holdings ever since the Spanish-American War, signaling a move away from empire as a moral concept.

3. Wartime Partnership: Allies With Reservations

The arrival of World War II demanded cooperation, and cooperation happened. Roosevelt was sympathetic to Britain’s struggles but had to navigate American laws like the Neutrality Act, which forbade direct aid initially. Enter the Lend-Lease program, allowing the US to supply Britain with war resources without outright entering the conflict.

Even amid this, tensions simmered quietly. Roosevelt wanted to dismantle empires, especially the British one, to forge a new, post-war world order centered on democracy and self-determination. Churchill’s refusal to let go of imperial holdings irritated Roosevelt deeply. The American president saw colonialism as outdated, while Churchill saw Britain without its empire as lost.

The relationship grew stranger when Roosevelt, surprisingly enough, felt closer to Stalin than to Churchill. Both Roosevelt and Stalin rejected the classic imperialist doctrine—even if reality was more muddy—and sometimes poked fun at Churchill’s old-fashioned notions of honor and empire.

4. Ideological Divides and Outside Influences

The divide wasn’t only personal. The American elite, with people like Harry Dexter White, key architect of the Bretton Woods financial system, privately favored communism’s potential. This outlook shaped their worldview of the Soviet Union and complicated relations with Churchill, who viewed the USSR with suspicion.

American perceptions sometimes gleamed with idealism or outright misunderstanding, filling gaps in knowledge with what they hoped was true rather than what was true—adding more strain to the alliance.

5. Conclusion: A Special Relationship With Limits

Despite all the friction, there’s no denying that Roosevelt and Churchill shared a unique bond. It was less a warm friendship and more a strategic partnership shaped by mutual respect and, at times, genuine admiration.

But it was an “uncomfortable alliance.” Roosevelt’s push for decolonization clashed with Churchill’s imperial identity. The US president demanded the UK “commit political suicide” by stepping away from empire, something Churchill simply could not accept.

“The men were therefore entangled in a special relationship, but united in an unhappy marriage.”

In other words, their alliance was essential to defeating Axis powers but riddled with ideological tension. Their personal warmth was balanced by political disagreements and vastly different visions of the future world order.

What Does This Mean for Our Understanding of History?

Understanding Roosevelt and Churchill as allies with a complicated personal and political relationship challenges the neat narratives of “best friends saving the world.” Real alliances, like real friendships, often hold contradictions.

Their story teaches us that shared goals can bring people together even when fundamental views clash—and that leadership sometimes requires brushing aside personal differences for a greater cause.

Next time you see those famous photos of the two leaders, consider the layers behind that handshake—a mix of friendship, power play, strategy, and unavoidable friction. How often do historical “friendships” peel back to reveal the grind of politics beneath?

In the end, Roosevelt and Churchill’s relationship reminds us of the complexity behind history’s great alliances. It was special, pragmatic, sometimes prickly, but undeniably impactful.