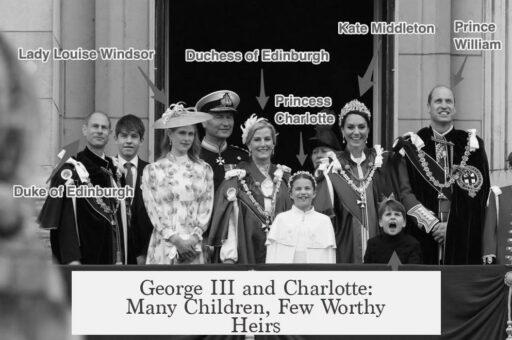

George III and Charlotte had 15 children, with 13 surviving into adulthood, but they ended up with surprisingly few legitimate heirs due to a complex mix of personal choices, parental influences, and political conditions. Their children often delayed or avoided marriage, married unhappily, or chose unsuitable partners. This limited the production of legitimate grandchildren, creating a succession puzzle that didn’t materialize until later generations.

Several factors explain this situation. First, George III and Queen Charlotte strongly desired a private family life. Unlike many royals, they avoided extravagant displays and maintained tight control over their children. George III was known as a strict patriarch. He emphasized obedience and modeled traditional values in his household.

This control extended to marriage decisions, especially for their daughters. Royal princesses normally married foreign royals or nobles of high rank, often arranged as diplomatic alliances. George III was reluctant or at times unable to organize such matches, especially as his health declined. As a result, many princesses married late—Charlotte married at 31, Elizabeth reportedly at 48, and Mary at 40—which diminished their chances of having many children.

Meanwhile, the princes enjoyed more freedom. They often pursued personal relationships without royal approval, some leading to illegal or non-royal marriages. For example, Prince Augustus married without consent, invalidating his children’s succession rights. Prince William lived with an actress and fathered 10 illegitimate children but had no legitimate heirs. Prince George IV detested his wife and separated from her, producing only one daughter, Princess Charlotte of Wales.

The marriage patterns of the elder children played a decisive role. Most elder siblings’ marriages were unhappy, reflecting a tension between personal desires and dynastic duties. George III and Charlotte hoped their children would follow their happy marriage example, but many rejected forced unions for political convenience. The elder children’s estrangement and unhappiness lessened their motivation to produce legitimate heirs.

Additionally, early deaths affected family dynamics. Alfred and Octavius died young, which likely increased the parents’ protectiveness and influenced later decisions. When Princess Charlotte—the only legitimate grandchild recognized as heir—died young, the anticipated continuation of the line vanished abruptly.

This death shifted urgency but also revealed long-standing reluctance among the siblings. Many princes only married or tried to produce heirs reluctantly or late in life. Prince Edward married at 50, having previously been in a long-term relationship with a married woman without children. Ernest, who married for love, had children after Victoria’s birth but mainly ruled the separate Hanoverian kingdom later.

Political factors complicated the succession. Multiple brothers stood in line, offering alternatives, but no one anticipated the need for a rapid succession solution until Princess Charlotte died prematurely. The princes had the freedom to marry whom they pleased but lacked motivation until the crisis forced action. The Hanoverian succession was thus safeguarded through extended kinship, though their limited legitimate offspring reflected their personal choices.

| Factor | Impact on Legitimate Heirs |

|---|---|

| Strict parental control | Delayed marriages, especially for princesses |

| Reluctance to arrange foreign royal marriages | Few timely alliances producing heirs |

| Unhappy elder children’s marriages | Reduced drive to secure dynastic succession |

| Princes’ unsuitable marriages or relationships | Illegal or non-royal unions limiting legitimacy |

| Early deaths of children | Increased overprotection and further delay |

| Death of Princess Charlotte | Succession crisis forced late marriages |

In essence, the royal family’s personal dynamics conflicted with traditional expectations. George III and Charlotte’s desire for a simpler, loving family life clashed with the dynastic needs of early 19th-century monarchy. Their children valued personal happiness over political expediency, producing few legitimate grandchildren. Their complex, delayed, or unhappy marriages combined with early deaths and political constraints to shape the limited legitimate succession that puzzled historians.

- Thirteen surviving children produced few legitimate grandchildren.

- Strict parenting delayed daughters’ marriages and limited their fertility.

- Sons often chose unsuitable or illegal unions, limiting recognized heirs.

- Early deaths increased parental protectiveness, shrinking marriage chances.

- Clearest heir, Princess Charlotte, died young, triggering late succession scramble.

- Political and personal factors combined to limit half-decent heirs.

How Earth Did George III and Charlotte End Up With So Many Children and So Few Half-Decent Heirs?

At first glance, it’s baffling: George III and Charlotte had 15 children, 13 surviving to adulthood, yet they left behind barely enough legitimate grandchildren to keep the royal line robust. So, how did this happen? Let’s unpack this royal mystery.

It wasn’t by lack of offspring, that’s for sure. But the story twists around “legitimacy,” parental choices, personal freedoms, and quite a few unhappy unions.

The Curious Case of Few Legitimate Grandchildren Despite Many Kids

Thirteen children sounds like a royal baby boom, right? Yet, legitimate grandchildren were surprisingly scarce. Why? Because many legit heirs just didn’t materialize, while illegitimate royal babies abounded in the shadows.

Legitimacy was king, and even if the royal blood ran wild elsewhere, only children born within proper marriage could secure the throne.

Parental Influence: A Double-Edged Sword

George III and Charlotte’s parenting style was pivotal. They craved a private, simple family life—not over-the-top royal luxury like Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. They ruled their brood like a domestic tyrant, aiming for well-behaved princes and princesses.

However, George married a German princess he saw as unlikely to challenge him—possibly a calculated move to keep the household peaceful but rigid.

The princesses? Overprotected, rarely allowed to marry foreign kings or princes until later life, which hurt their fertility and chances to produce heirs. The princes? They had more freedom, often marrying unsuitably or living with mistresses.

Fun Fact: From 1772 onward, royal family members needed George’s permission to marry. This led to illegal “marriages” among princes—sometimes they just threw caution (and legality) to the wind!

The Reluctant Marriage Market: Why So Many Marriages Were Delayed or Unhappy

The elder children were matched with people of rank, but many marriages were unhappy. George IV, for example, detested his wife and separated, despite having one daughter.

His brother Frederick also had an unhappy marriage—likely one reason they left no legitimate heirs.

Meanwhile, William IV, the famous “bachelor who lived with an actress,” fathered 10 illegitimate children but had no lasting legitimate heirs. His marriage came late and produced only two daughters who sadly died young.

Edward waited to marry until 50—and only then because a succession crisis forced his hand. He’d been in a long-term relationship with a married woman but had no children from it.

Passing the Buck: The Burden of Inheritance Was Everyone’s Problem, and No One’s

When Princess Charlotte—who many expected to bear the next generation—died young, the royal family collectively had a shock. Prior to her death, many younger siblings had assumed she’d secure the line, allowing them to enjoy freer lives.

After her death, the scramble began—too late for some. The royal siblings had not prepared to take up the mantle. The responsibility to marry suitably and produce heirs passed along in a kind of royal game of hot potato.

Question to bounce around your head: Could this royal laissez-faire explain why “many children, few heirs” became the family motto?

Princesses: Overprotected, Late, and Often Childless

The princesses were extremely close to their parents, especially Charlotte. Rather than being sent abroad for politically strategic marriages, they often married late or not at all, hampering fertility and succession.

- Charlotte married at 31 (a bit late for her era).

- Elizabeth married at 48, with rumors of an illegitimate child but no legitimate heirs.

- Mary married at 40—again, late for bearing children.

The princesses’ marriages rarely produced the next generation of heirs, and their late marriages didn’t help.

Princes Pursued Freedom Over Dynastic Duty

The princes got to enjoy the freedoms of their rank, often chasing personal happiness over political convenience.

For instance, Augustus married without royal permission to a woman who didn’t fit the expectations. His marriage and children were unrecognized by the crown. On the other hand, Adolphus married suitably and had three children, but his lineage was overshadowed by Victoria’s in the succession order.

Deaths and Trauma: A Royal Family Under Pressure

Alfred and Octavius, two of George III’s sons, died young. This likely made George and Charlotte even more protective, complicating the timing and management of their other children’s marriages and offspring.

How Succession Crisis Sparked Late but Frantic Marriages

Contrary to popular belief, the princes were already considering marriage before Princess Charlotte died unexpectedly.

William had left his wife in 1811 and sought a foreign royal consort. Ernest married only in 1815, a few years after Charlotte’s death. The Hanoverian succession offered alternatives through different brothers, lessening the urgency for immediate heirs.

The death of Princess Charlotte accelerated the pressure but didn’t create it.

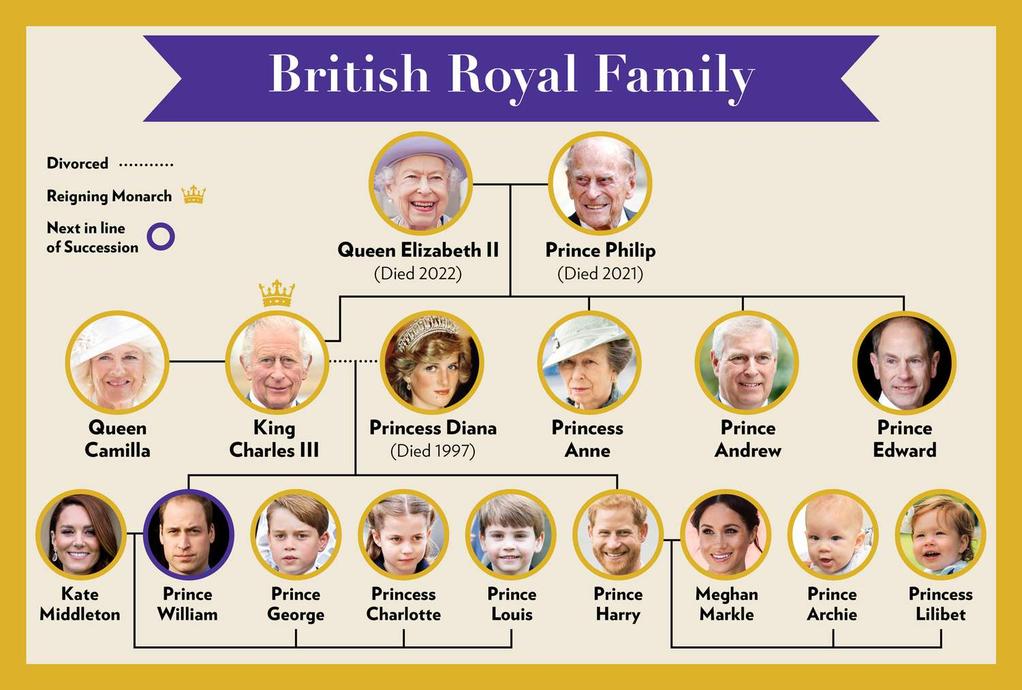

Example of the Unexpected Heir: Victoria

Edward’s late marriage and eventual birth of Victoria at 50 was a royal curveball. She would become one of the most famous monarchs, but she was only born because the older siblings failed to produce surviving heirs.

Ernest’s children, who married for love and were tolerated rather than fully embraced, ended up inheriting the Hanoverian throne—underscoring the shifting royal lines due to the complex family dynamics.

A Unique Parenting Recipe With Unexpected Results

George III and Charlotte tried to create a calm, private backdrop for their children, different from flashy royal courts. But George’s iron-fisted control clashed with his sons’ thirst for independence and daughters’ limited freedom.

Their insistence on “well-behaved” kids ironically spawned rebellious princes settling for unsuitable partners and delayed marriages for princesses, shrinking the legitimate pool of heirs.

What Can We Learn From This Royal Saga?

- Sometimes, control backfires. George and Charlotte’s strict household didn’t produce a strong next generation as planned.

- Happy marriages matter. The royal desire for spouses they loved instead of dynastic alliances probably sacrificed succession for personal contentment.

- Timing is everything. Delayed marriages for princesses and reluctant grandkids that only came after a crisis showcase the delicate dance of royal succession.

In the end, the royal family’s tangled web of expectations, control, individual desires, and untimely deaths crafted a legacy of “so many children, so few half-decent heirs.”

So, next time you think about royal dramas, remember: even kings and queens can’t always manage their family trees as neatly as they do their kingdoms.

Got thoughts on royal parenting? Think it could have been different? Drop a comment below!

Why did George III and Charlotte have many children but so few legitimate grandchildren?

They had 13 surviving children, yet few legitimate grandchildren. This was partly because some royal offspring were illegitimate. Also, early deaths and delayed or unhappy marriages limited descendants.

How did George III and Charlotte’s parenting affect their children’s marriages?

George III demanded strict obedience and control over his children’s marriages. Princesses faced permission delays, often marrying late, reducing chances for heirs. Sons rebelled with unsuitable partners.

Why were the marriages of George III’s elder children unhappy and how did this impact succession?

Elder children married for rank, not love, leading to unhappy unions. This drained their motivation for producing heirs. The expected succession lines faltered, shifting hopes to younger siblings.

How did the princes’ personal choices influence the shortage of heirs?

Some princes married late or to unsuitable partners. For example, Edward married at 50 with one child, William had many illegitimate children but few legitimate heirs. These choices thinned the direct succession line.

What role did Princess Charlotte’s death play in the succession crisis?

Princess Charlotte was seen as key to continuing the dynasty. Her death caused urgency and panic among siblings, who had delayed their duties, creating a shortage of qualified heirs when she passed.