Timbuktu became a widely recognized symbol of a faraway, exotic place in Western and Anglo popular consciousness due to a combination of its historical wealth, cultural significance, European accounts, and enduring myths that outlasted factual corrections.

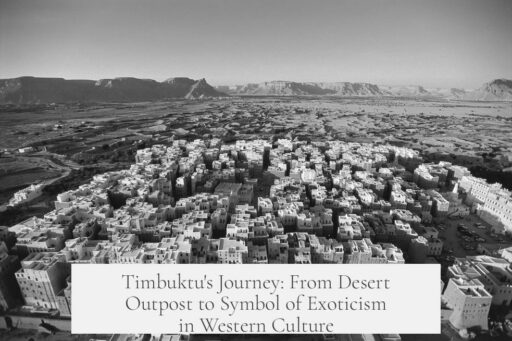

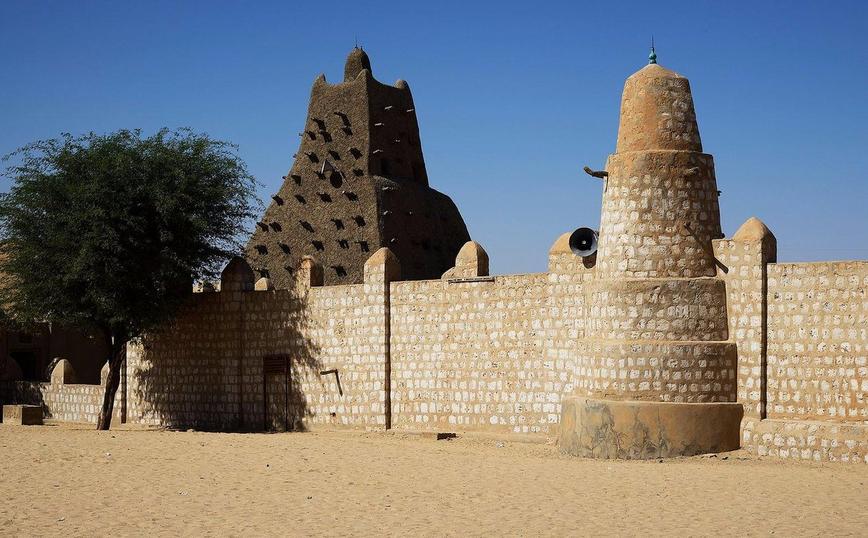

The city’s rise began with its strategic location on the edge of the Sahara Desert near the Niger River. Founded around 1100, Timbuktu grew from a small settlement into a crucial hub for the trans-Saharan caravan trade. It handled gold, salt, and slaves, making it economically vital. In 1325, Mansa Musa, ruler of the Mali Empire, peacefully annexed Timbuktu, marking the start of its golden age.

Mansa Musa’s 1324-25 hajj (pilgrimage) to Mecca was pivotal in establishing Timbuktu’s legendary status. Known as possibly the richest person in history, he traveled with a massive entourage and distributed so much gold along the route that it destabilized local economies, notably crashing the value of gold in Cairo for over a decade. This event was dramatically recorded by contemporary Arab historian Al-Umari, who described how the influx of gold depressed its price in Egypt from that time onward.

This wealth captured European imaginations. The 1375 Catalan Atlas visually immortalized Mansa Musa holding a large gold nugget standing next to the city labeled “Tenbuch” (Timbuktu). This depiction helped solidify the image of Timbuktu as a land overflowing with gold, thus fueling fantasies across Europe.

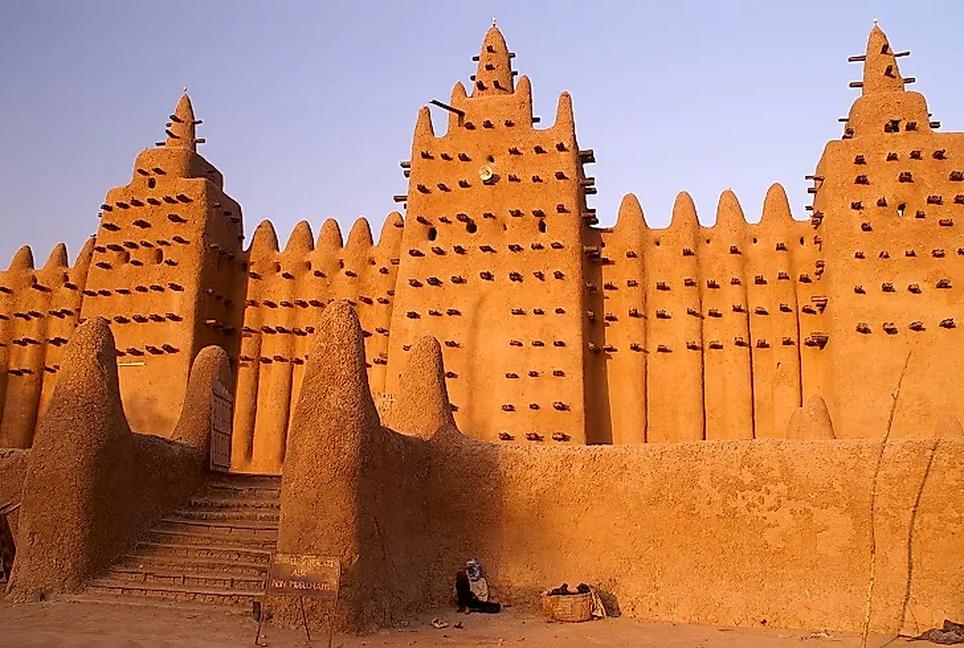

Apart from wealth, Timbuktu was renowned as a center of Islamic culture and learning. Following Mansa Musa’s annexation, it became home to scholars and religious leaders. The city’s universities and mosques attracted students, fostering intellectual richness that added depth to its exotic appeal. This dual identity, combining material wealth and scholarship, enhanced Timbuktu’s prestige further in Western perceptions.

The next significant influence came from Leo Africanus, a Moorish scholar and traveler. Visiting around 1510, detailed descriptions of Timbuktu’s wealth, especially the use of gold nuggets and cowrie shells as currency, reached Europe through his 1550 book, Description of Africa. His accounts were among the few quasi-academic European sources on Africa’s interior at the time, shaping many Europeans’ understanding and cementing Timbuktu as a land of mysterious richness.

For centuries, Timbuktu maintained this myth largely because Europe lacked updated, reliable reports about it. As maritime trade routes replaced trans-Saharan ones, Timbuktu declined economically. Yet, the city’s legendary reputation endured, so much that by 1824, the Paris Société de Géographie offered a large reward to anyone who could reach Timbuktu and report back.

When explorers like René Caillié arrived in 1828, the reality challenged the myth. Caillié found Timbuktu small and unimpressive, with limited commerce. Heinrich Barth’s visit in 1853 confirmed this more sober reality. Despite these revelations, the romanticized image of Timbuktu as a secluded, wealthy city persisted in popular imagination. The disparity between fact and legend was too wide to erase easily.

Timbuktu’s mythical status survives because its old legends remain more captivating than the mundane truth of a declining trade town. It became a shorthand for any distant, exotic, and seemingly unreachable place, deeply embedded in Western culture and language.

| Factors Contributing to Timbuktu’s Exotic Status |

|---|

| 1. Mansa Musa’s spectacular pilgrimage displaying immense wealth. |

| 2. Leo Africanus’s influential, detailed European accounts. |

| 3. Timbuktu’s role as an Islamic intellectual and religious center. |

| 4. Long gaps in reliable information allowing myths to grow. |

| 5. European explorers’ factual reports failing to dispel legends. |

| 6. The enduring appeal of romanticized, exotic images in Western culture. |

- Timbuktu’s geographical position made it a key trade hub in West Africa.

- Mansa Musa’s legendary gold pilgrimage reached and stunned Europe.

- Its intellectual heritage added to its exotic allure.

- European accounts created and reinforced myths of immense wealth.

- Limited direct knowledge allowed fantasies to persist over centuries.

- Despite factual exploration, the myth remained entrenched in Western culture.

How Did Timbuktu Become One of the Go-To “Far Away/Exotic” Places to Reference in Western/Anglo Popular Consciousness?

In simple terms: Timbuktu earned its legendary status in Western and Anglo popular imagination because of a mix of incredible real wealth, dazzling stories from travelers, and a thick fog of mystery around its true nature for centuries. This combination transformed a once-bustling Saharan trade hub into the golden star of exotic places in the Western mind.

Let’s unpack how a once-small settlement on the edge of the Sahara became synonymous with “far-flung, mysterious riches” and why the legend of Timbuktu still captivates us today.

From a Humble Desert Outpost to a Golden Crossroads

Timbuktu was founded around 1100 CE as a modest settlement, strategically hugging the southern edge of the Sahara Desert near the Niger River. Not the most glamorous start, but this location was perfect. It sat squarely on the trans-Saharan caravan routes that shipped gold, salt, and unfortunately, slaves, across West Africa.

Trade routes here meant money, influence, and—most importantly—connections. Around 1325, the Mali Empire under Mansa Musa annexes Timbuktu peacefully, catapulting the city to a new level of importance.

So why did Mansa Musa matter so much? Ask any history buff: he’s famously called the richest person who ever lived. His reign coincided with West Africa’s golden period for gold production. That gold wasn’t just about wealth; it was about power and reputation.

Mansa Musa’s Legendary Pilgrimage: A Gold Rush for the Imagination

Picture this: in 1324, Mansa Musa embarks on his pilgrimage to Mecca. But this isn’t your average spiritual journey. He’s traveling with a HUGE entourage, including thousands of attendants, camels laden with gold, and gifts fit for kings—and he’s generous to a fault.

The story goes that in Cairo, Mansa Musa’s lavishness literally crashed the economy. He handed out so much gold that its value plummeted for a decade. Contemporary accounts, like those of Arab historian Al-Umari, describe how the gold flood made the city’s coin value tumble for over ten years. That’s no small feat! Imagine throwing a party so big it wreaks havoc on a country’s economy.

This dazzling display of wealth was legendary. When Europeans began hearing about this pilgrimage, Timbuktu’s name became linked with unimaginable riches. The famous 1375 Catalan Atlas shows “Tenbuch” (Timbuktu) at Mansa Musa’s feet, gleaming with gold. This map visualization practically stamped Timbuktu on Europe’s mental treasure map.

More Than Just Gold: Timbuktu the Intellectual Beacon

But Timbuktu wasn’t just about gold (surprise, surprise). After Mansa Musa’s rule, the city blossomed as a center for Islamic culture, trade, and education. It hosted one of Africa’s greatest universities, with scholars flocking from across the Muslim world.

This intellectual glow added layers to the city’s appeal, making it not just a place of riches but also of profound knowledge and spirituality.

This blend of material and intellectual wealth made Timbuktu a beacon of exotic sophistication. For Westerners, a wealthy city with an esteemed university deep in the “unknown” African interior was irresistible fodder for the imagination.

Leo Africanus: The Man Who Painted Timbuktu in Europe’s Eye

Fast forward to the early 1500s. The Western world’s curiosity about Africa’s interior was at a fever pitch, but authentic knowledge was scarce. Enter Leo Africanus, a Muslim traveler and scholar who visited Timbuktu around 1510.

His book, Description of Africa (1550), became Europe’s go-to source on this mysterious land. His accounts emphasized the city’s wealth and the richness of its people. He described kings with treasures of coins and gold nuggets, explaining that pure gold nuggets were everyday currency and small purchases used cowrie shells imported all the way from Persia.

This wasn’t dull academic writing. It was vivid storytelling that further amplified Timbuktu’s image as a place of untold riches and exotic customs. With so little European first-hand experience, Africanus’ descriptions gained enormous influence—practically defining what Europe thought of West Africa for generations.

The Void of Truth: How Silence Fueled the Myth

What happens when no one can verify these grand tales? The story grows, of course.

Timbuktu’s declining importance by the 17th century, due to shifting trade routes favoring sea travel, meant fewer travelers visiting or bringing updates. The European imagination ran wild in this information vacuum.

So strong was the allure that as late as 1824, the Parisian Société de Géographie dangled a 9,000-franc reward (generous at the time!) for someone to travel to Timbuktu and send back true, detailed descriptions.

This says a lot. When you are desperate to know, but actual knowledge is scarce, myths fill the gap. And Timbuktu was a fertile ground for that myth-making.

The Actual Arrival: When Reality Meets Expectation

Finally, in 1828, René Caillié reached Timbuktu. If you imagine a triumphant explorer bursting through exotic doors into glittering palaces—forget it. Caillié’s experience was a letdown.

He wrote,

“I looked around and found that the sight before me did not answer my expectations. The city presented nothing but a mass of ill-looking houses. It was neither large nor populous as fame reported.”

Later, Heinrich Barth, arriving in 1853, confirmed Caillié’s observations. Instead of a city bursting with gold and wealth, Timbuktu was a quieter, more modest place, a shadow of its glory days.

But here’s the twist: despite these factual reports, the myth didn’t die. The contrasting reality could not dismantle centuries of mythologizing. The allure of Timbuktu’s romantic image lingered like stubborn desert dust.

Why Does Timbuktu Still Mean “Far Away and Exotic” to Us?

Legends tend to outlive facts, especially when the legends are more glamorous. Timbuktu’s image survived in Western minds as the quintessential symbol of distant riches and mystery.

It became shorthand for “the middle of nowhere” or “a place beyond reach and reason,” a mental escapade more than a historical fact. Even today, we use “Timbuktu” in conversations as a playful stand-in for some far-flung, somewhat mythical place.

So, Timbuktu’s myth persists as a cultural symbol rather than a literal place—a symbol baked from genuine history, heroic storytellers, and centuries of imagination fueled by silence and distance.

What Can We Learn From the Timbuktu Story?

- History and Myth Intertwine: Sometimes, legends grow not from lies but from gaps filled with awe and wonder.

- Information Gaps Matter: The fact that few Europeans had direct contact with Timbuktu for centuries gave the city mythic status.

- Stories Shape Perception: The dramatic tales of Mansa Musa’s pilgrimage and Leo Africanus’ vivid accounts show how storytelling crafts reputations.

- Reality vs Romance: Even when explorers report facts, popular culture can cling to the more enticing myths.

- Exoticism Has Longevity: Timbuktu continues to inspire imaginations as much as any fictional fantasy land.

So next time you hear “Timbuktu” in a sentence meaning “a faraway, exotic place,” remember: it’s a shorthand steeped in history, gold, scholars, and legend. Not just a dot on a map, but a story that traveled farther than any caravan.

Why did Mansa Musa’s pilgrimage make Timbuktu famous in Europe?

Mansa Musa’s 1324-25 pilgrimage displayed immense wealth by giving away gold freely.

Stories of his generosity spread, causing Europe to see Timbuktu as a land of vast riches.

This was reinforced by maps like the 1375 Catalan Atlas depicting Timbuktu at his feet.

How did Leo Africanus influence Western views of Timbuktu?

Leo Africanus wrote one of the first detailed accounts of Timbuktu in 1550.

His descriptions highlighted the city’s wealth and exotic culture during a time when Europe lacked reliable information about Africa’s interior.

Why did Timbuktu remain a mysterious and exotic place in Western imagination despite decline?

Europe had little updated knowledge after maritime trade replaced trans-Saharan routes.

This lack of information let myths about Timbuktu’s wealth and mystery thrive for centuries.

Efforts like the 1824 Parisian reward to explore Timbuktu show its legendary status.

What disproved the myth of Timbuktu as a wealthy, grand city?

Explorers René Caillié (1828) and Heinrich Barth (1853) reported a smaller, less prosperous city.

They described few riches and modest commerce contrary to European legends.

Why does Timbuktu still symbolize a “far away” exotic place in Western culture?

Its historical role as a rich trade and learning center sparked early imaginations.

Long-lasting myths combined with slow, disappointing factual reports created a romanticized image.

This image remains embedded in Western popular culture as a symbol of remote mystery.