The Roman aristocracy initially viewed and treated plebeians as socially inferior and politically excluded, but this changed significantly over time during the Republic.

In the early Republic, society was sharply divided between patricians and plebeians. Patricians were a small elite group of aristocratic families who controlled all major political and religious positions. Plebeians comprised the rest of the population, excluded from power and often marginalized. The patrician monopoly sparked the “struggle of the orders,” a prolonged plebeian civil rights campaign aimed at securing political equality.

Over time, plebeians gained important rights. The landmark law of 367 BC ensured that at least one consul would be a plebeian. Other political and religious offices gradually opened up. This reduced patrician exclusivity but maintained social gaps.

By the late Republic, the strict patrician-plebeian distinction had lost much of its relevance. Patricians remained a recognized social group but no longer formed the dominant political class by default. Many former patrician families had diminished influence. In some cases, being a patrician limited political opportunities. For example, Publius Claudius Pulcher, a patrician, had to be adopted into a plebeian family to run for the tribunate, a position normally closed to patricians. He changed his name to Publius Clodius Pulcher following this move in 59 BC.

By then, “plebs” referred broadly to common people outside the senatorial and equestrian classes rather than specifically to non-aristocrats. This shift reflected social mobility and a more complex political landscape.

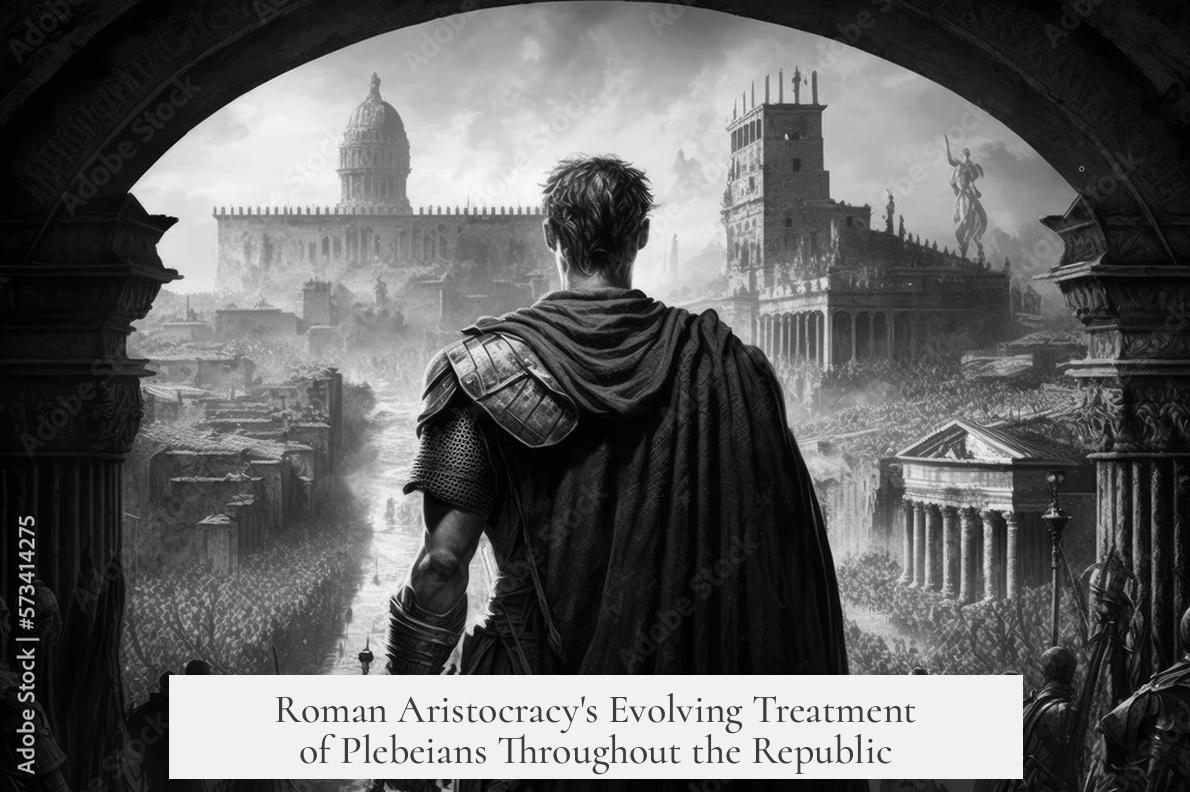

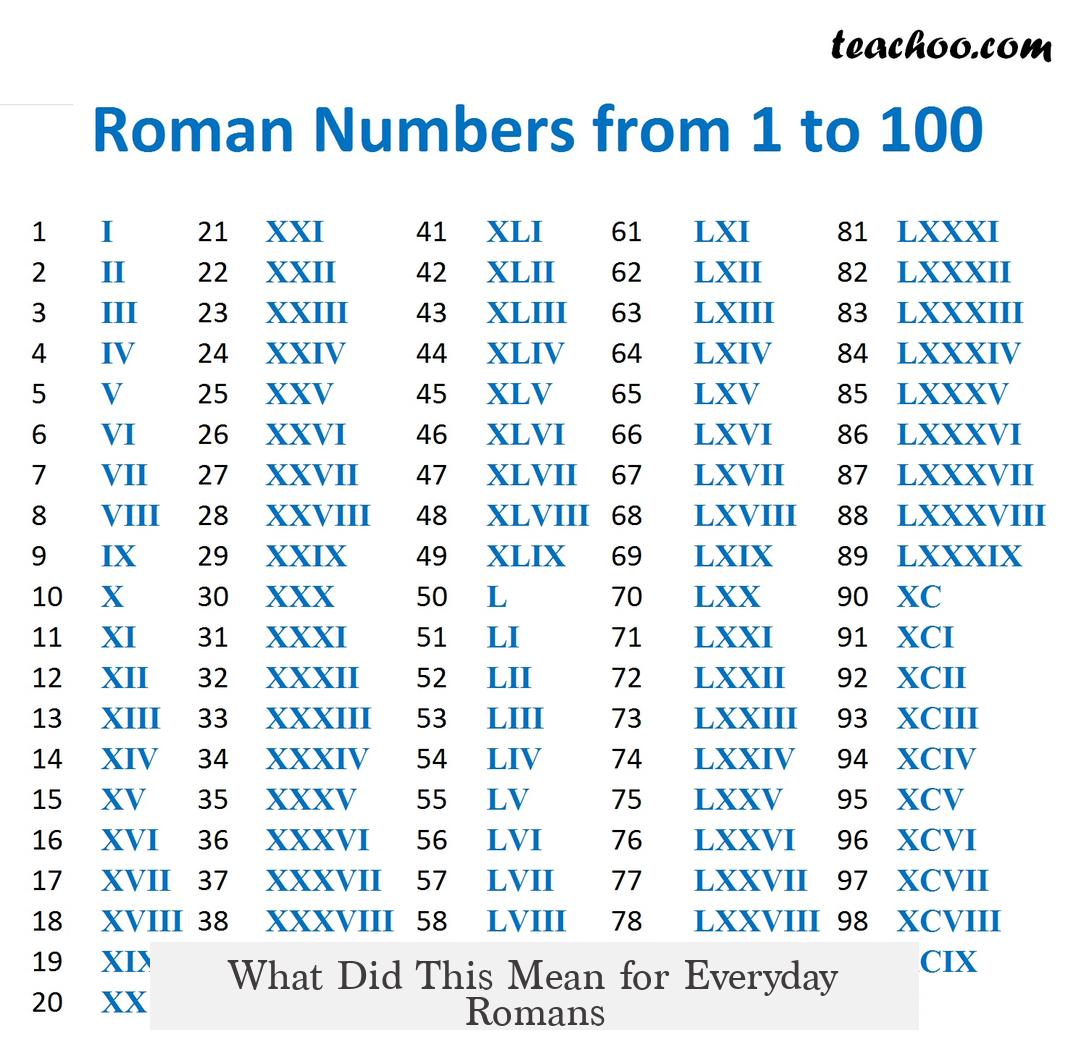

| Period | Aristocratic View/Treatment of Plebeians | Political Status |

|---|---|---|

| Early Republic | Patricians monopolize power, exclude plebeians | Plebeians excluded from offices initially; struggle of the orders begins |

| Mid Republic | Gradual inclusion of plebeians in political offices | Law of 367 BC grants plebeian consuls; other offices open up |

| Late Republic | Patrician-plebeian distinction becomes redundant | Plebeians include broader common classes; patricians lose monopoly and prestige |

- Initially, patricians viewed plebeians as inferior and excluded them from power.

- The struggle of the orders forced gradual political integration of plebeians.

- Late Republic saw weakening of patrician dominance and broader commoner identities.

- Political roles once closed became accessible to plebeians and sometimes closed to patricians.

How Did the Roman Aristocracy Treat and View Plebeians? Were They Treated Differently at Different Points in the Republic?

In the Roman Republic, the aristocracy originally treated plebeians as second-class citizens, but over time, this rigid social divide softened due to political struggles and legal reforms. However, the nature of their treatment shifted significantly from the early to the late Republic.

Let’s unpack this fascinating historical relationship, peppered with power struggles, legal battles, and social evolution.

The Early Republic: Patricians vs. Plebeians—Bitter Rivals or Reluctant Roommates?

Back in the early days of Rome, society was pretty straightforward—and a little unfair. The patricians were a tiny elite group—think exclusive invite-only clubs—but for life. These aristocratic families controlled every big decision, every religious role, and every important office. Meanwhile, the plebeians were, well, everyone else.

The plebs lived like a vast crowd sidelined from politics. Imagine a huge stadium where only a few VIP seats are reserved for patricians, and the rest have to cheer from the cheap seats. This fed resentment and a burning desire for change—the famous Struggle of the Orders.

This struggle was essentially the Roman version of a civil rights campaign. The plebeians fought tooth and nail to claw their way into the halls of power. The early Republic’s history reads like a slow-motion battle for equality, where the underdogs gradually snagged political rights one by one.

One landmark victory arrived in 367 BC with the Law of Licinian-Sextian. This law guaranteed that at least one of the two annually elected consuls had to be a plebeian. It was more than symbolic; it cracked open the doors to more offices previously locked tight to patricians.

- Patricians controlled politics and religion at first.

- Plebeians demanded and gained civil rights over decades.

- The 367 BC law was a major plebeian political win.

By the time this law passed, the distinctions between the two classes began to blur, but tensions lingered. The patricians saw plebeians as challengers to their traditional privileges. On the flip side, the plebs saw aristocrats as obstacles to fairness and representation.

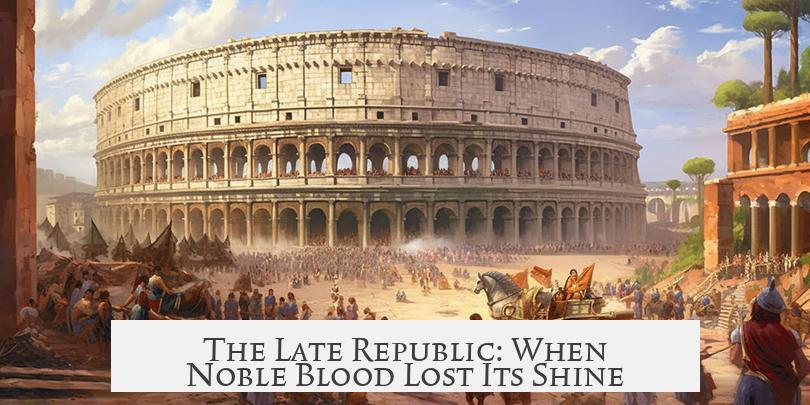

The Late Republic: When Noble Blood Lost Its Shine

Fast forward a few centuries. The world changes. The patrician-plebeian divide becomes less of a social chasm and more of a historical footnote. By the late Republic, many plebeian families had grown rich and powerful. The aristocracy now included wealthy plebs who bought influence or lived aristocratic lifestyles.

Meanwhile, patrician status became less about power and more about pedigree. Surprising as it sounds, being a patrician could even hurt your political career! A great example is Publius Claudius Pulcher—an aristocrat who couldn’t run for tribune because that office was reserved for plebeians.

So, Pulcher did something drastic: he got adopted into a plebeian family. Yep, you read that right! He switched his social team to unlock political opportunities, becoming Publius Clodius Pulcher in 59 BC. Imagine the drama at family dinners!

This tells us a lot about the shifting landscape: the original aristocratic bloodline lost some shine. What mattered more was power and influence, not ancient family titles.

By this time, the term “plebs” generally meant the common people—anyone outside the senatorial or equestrian ranks. It wasn’t so much a caste as a catch-all for the non-elite majority.

What Can We Learn? A Changing View, A Changing Treatment

So, were plebeians treated differently at different points? Absolutely.

- Early Republic: Patricians held the keys to power, treating plebeians like outsiders with restricted rights.

- Mid Republic: Plebeians won gradual access to offices and religious roles through political struggle.

- Late Republic: The patrician-plebeian distinction faded. Wealth, influence, and political savvy mattered more than birth.

The Roman aristocracy’s treatment of plebeians changed from exclusion to grudging acceptance, then to a more fluid social landscape where old class lines lost meaning.

Practically speaking, plebeians became essential players in Rome’s political and social scenes. Their victories in office-bearing rights paved the way for many modern ideas of citizenship and civil rights.

What Did This Mean for Everyday Romans?

If you were a plebeian in early Rome, you might have felt like a guest in your own house, watching aristocrats make decisions without you. But by the late Republic, if you were wealthy or smart enough (yes, even as a plebeian), you could climb the social ladder.

Now, imagine being a patrician in those times. You’d have to adapt fast or find yourself sidelined by newcomer plebeian nobles. Social status hinged on more than just family name; savvy politics and alliances ruled the day.

Final Thought: Can This Ancient Tale Teach Us About Social Mobility?

Rome’s history reminds us that social barriers are not always permanent. Change often comes through persistent struggle and smart compromises.

So next time you hear about “noble” versus “commoner,” think of Rome’s plebeians. They started on the sidelines but ended as power players shaping one of history’s biggest empires. It’s a story of grit, adaptation, and the slow march toward equality—or at least, a better shot at it.