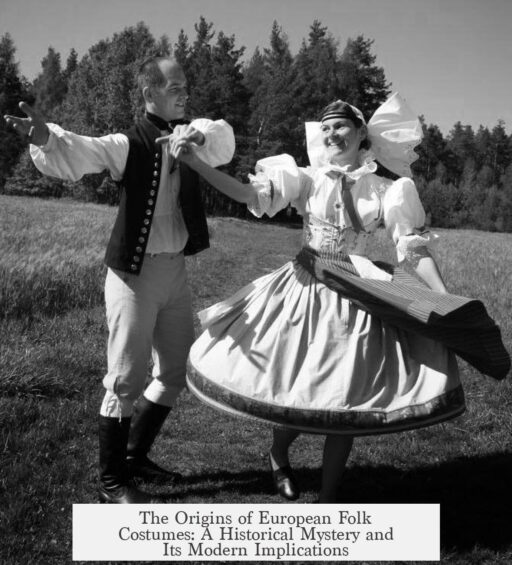

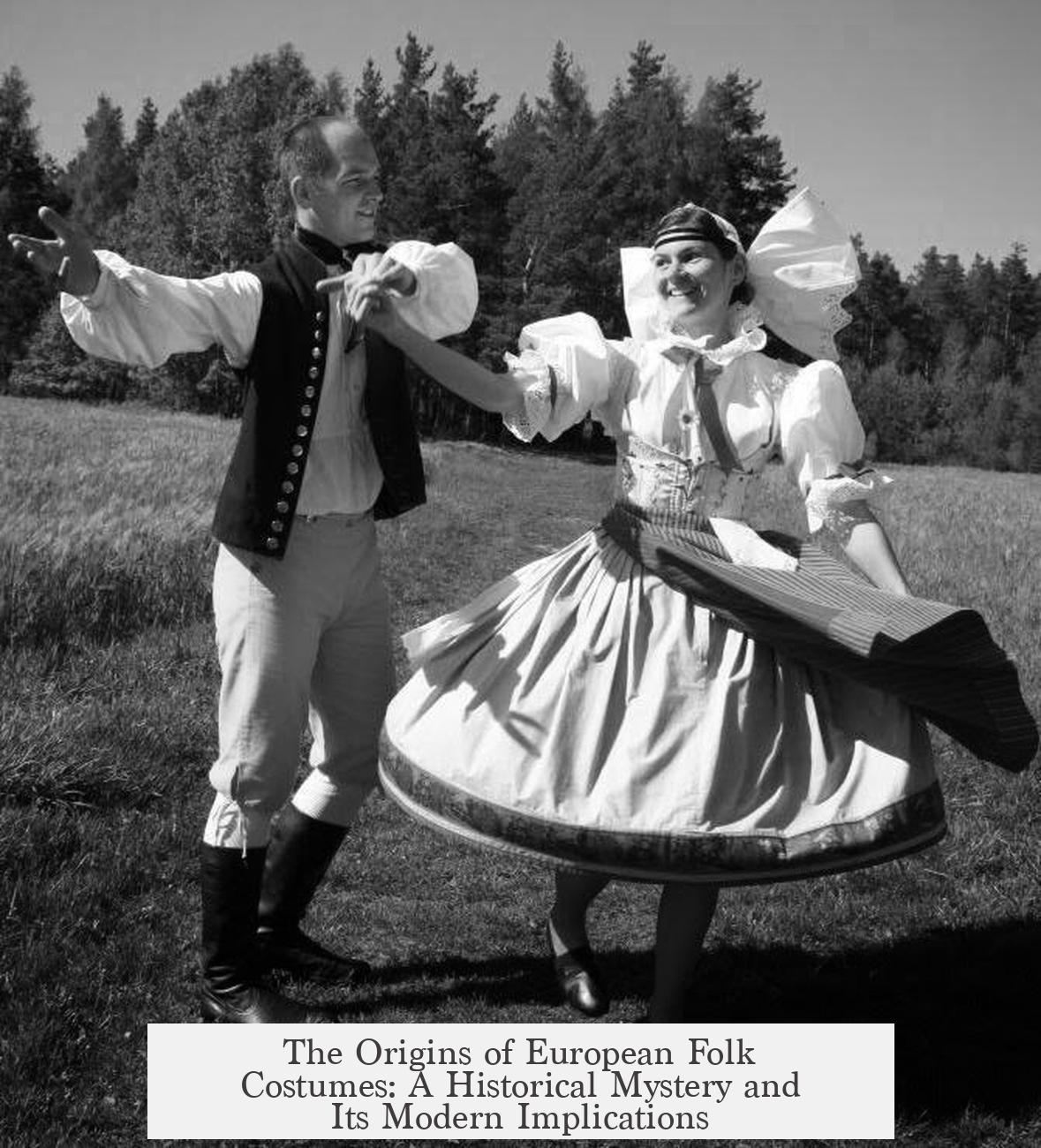

European traditional and folk costumes arose from distinct regional apparel worn prior to modern industrialization, but many so-called “traditional” outfits are idealized or revised forms shaped in the 19th and 20th centuries. Historically, people did dress in region-specific styles, but what is considered “folk dress” today often differs from everyday attire and reflects cultural revival movements rather than constant historical usage.

Before the late eighteenth century, Europe displayed a variety of regional dress styles. Visitors traveling through different countries or areas would notice distinctive clothing reflecting local materials, customs, and social roles. Rural inhabitants especially maintained unique outfits, even as urban fashion began standardizing over time. For example, artworks and fashion books from the 17th and 18th centuries clearly distinguish women’s regional dresses showing differing headpieces, sleeves, collars, and bodice designs.

One 1662 atlas of global costumes illustrates women from Antwerp, England, and Cologne, highlighting contrasting silhouettes and accessories. The Antwerp woman wore a cloak with elaborate headwear and slashed sleeves. The Englishwoman’s gown featured narrower sleeves and a sheer collar, while the Cologne woman wore a broad ruff and had bare hair, differing subtly in structure like the use or absence of stays.

By the late 18th century, collections depict costumes from Spanish, Slovakian, and Swiss regions showing common garments such as shifts, petticoats, aprons, and stays or corsets for women. Men’s attire also exhibited regional variations but shared base elements like linen shirts and waistcoats. These examples confirm continuity in certain garment types that survive today in many folk costumes. The Carniolan outfit, for instance, closely resembles lederhosen, a traditional Alpine garment.

Despite historical evidence of diverse dress, the clothing depicted usually represents “best” or ceremonial apparel rather than daily wear. Peasants and laborers owned fewer garments, and their everyday clothes were practical, often faded or worn from work. The idealized costumes from paintings and engravings therefore differ significantly from the rougher textures of everyday use.

The 19th century brought industrialization and mass production of textiles and garments, leading to widespread adoption of increasingly uniform urban fashion. Rural areas gradually abandoned many traditional styles in favor of these industrial fashions. Growing communication and transport networks accelerated this change.

As traditional rural dress faded, middle and upper classes reacted by preserving and reviving elements of folk costumes to safeguard national heritage. These folk dresses became symbols of national identity, emphasizing the rural working class as the cultural root of the nation. This revival sometimes involved standardizing or beautifying regional clothes to suit aesthetic and symbolic needs.

Modifications or simplifications frequently occurred during this revival. For example, the famous white coiffe of Alsace became generalized to represent the region in nationalist movements, although it was originally worn only in northern Alsace. In Norway, Hulda Garborg documented traditional costumes but enhanced some designs, promoting Hardanger dress as a pan-Norwegian icon rather than representing all local variations equally.

In Germany, many traditional costumes (*Tracht*) are adapted from early 19th-century originals but simplified and stylized. Modern versions like the dirndl, popular at Oktoberfest festivals, incorporate 20th-century fashion influences rather than strictly reflecting historic dress. These folk costumes serve more as cultural symbols than literal continuations of historical attire.

| Aspect | Historical Reality | Modern Folk Costume |

|---|---|---|

| Regional Variation | Distinct local styles in rural and urban areas, changing by region and era | Often a standardized or idealized version of one regional type |

| Everyday vs. Ceremonial | Daily dress was practical and worn; “best clothes” worn on special occasions | Revived/festive outfits based on ceremonial or idealized versions |

| Evolution | Slow change until industrialization; rural dress shifted as mass fashion spread | 19th/20th century revival movements created folk costume identities |

| Authenticity | Continuous use of many traditional clothing elements | Modifications, aesthetic changes, and cultural symbolism often predominate |

The widespread belief that historical Europeans never dressed in regional styles stems partly from conflating everyday worn clothes with ceremonial or well-kept costumes. Clothing in historical representations often highlighted ideal or formal attire. As average garments wore out, folks preserved clearer memories of special outfits, which later fueled folk costume revivals.

- European folk costumes primarily reflect regionally distinct dress before industrialization and urban fashion standardization.

- Historical images depict idealized or ceremonial clothing rather than everyday wear.

- Mass production and urban fashion in the 19th century reduced regional dress diversity.

- Folk costumes today are often revived, modified, or standardized symbols embodying national or regional identity.

- Elements of traditional dress genuinely persisted but evolved as cultural markers beyond literal historical usage.

How Did So Many European ‘Traditional/Folk’ Costumes Come to Be, When Historically, People Didn’t Dress Like That?

The main reason so many European ‘traditional’ costumes exist today, despite historical evidence showing that people rarely dressed exactly like that, is because these costumes evolved from real but varied regional clothing styles, later idealized, simplified, and revived as symbols of national identity. It’s a tale of regional variance, social shifts, industrialization, nostalgia, and a dash of cultural creativity.

Sounds complicated? It is. Yet, it’s fascinating how what began as everyday rural dress transformed into the charming, colorful folk costumes we now proudly display at festivals, national holidays, and Oktoberfests.

Distinct Regional Styles: Real Threads of Europe’s Past

Long before mass media and globalization, different regions in Europe had their unique ways of dressing. These were not “costumes” in the way we think of them today, but rather practical, everyday clothing that varied by local customs, climate, resources, and traditions. A visitor in 17th century Europe, for example, would witness a tapestry of regional styles.

Historical records such as the 1662 Livre curieux showcase diverse women’s attire — a woman from Antwerp proudly wears a cloak with a striking headpiece and long overskirt, while an Englishwoman opts for narrower sleeves and a sheer collar. Then there’s the Cologne woman sporting a broad ruff and hair pulled back tightly. These outfits shared silhouettes but flaunted distinct details that marked regional identity.

Evolution Over the Centuries: 18th Century Examples

Fast forward to the 18th century, and these variations continued. The 1788 publication Costumes civils actuels de tous les peuples connus depicts women from places as far-flung as Salamanca, Murcia, Carniola, and Bern. Each outfit followed basic clothing principles—shifts, petticoats, aprons, stays or corsets—but colors, cuts, and combinations reflected their particular culture and environment.

Men’s dress echoed a similar variance. The Carniolan outfit, often likened to lederhosen today, derived from historical rural dress rather than being a modern invention. This continuity debunks the myth that folk costumes are purely modern creations with no historical basis.

Why Don’t Historical Records Show More of These Costumes?

Good question! Historical illustrations usually depict people in their “Sunday best”—the brightest, cleanest clothes worn for special occasions, church, or to impress visitors. Daily wear, especially of the working peasantry, tended to be simpler, worn, and less vibrant due to hard labor and limited wardrobes.

So while many peasant workers had one or two practical suits for everyday chores and a special set reserved for church or town visits, historians and artists often immortalized the latter. The everyday work clothes, often faded and threadbare, rarely made it into grand artistic or written records. This created a skewed impression of what people “usually” wore.

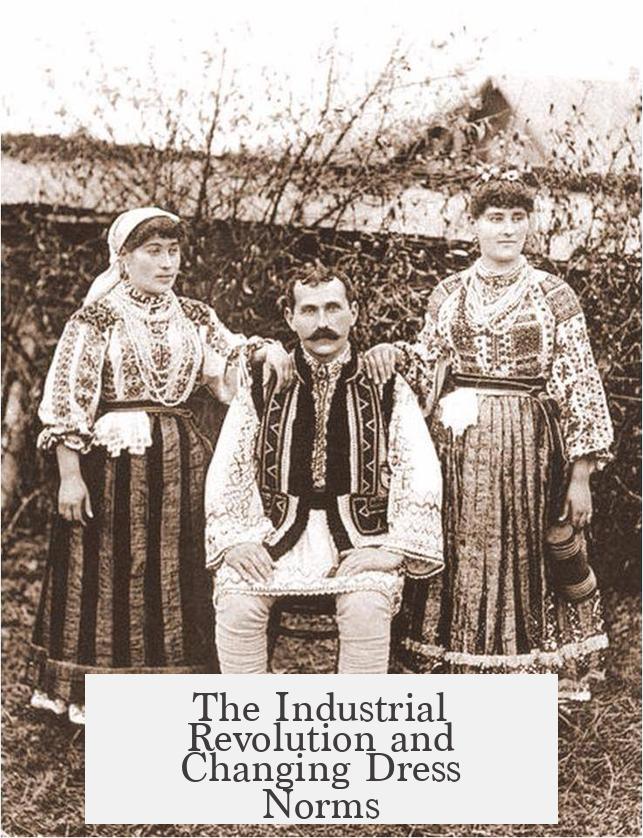

The Industrial Revolution and Changing Dress Norms

By the 19th century, the industrial revolution altered everything. Textile production became mechanized. Fashion trends, largely dominated by French and English elites, spread faster through mass media, influencing even rural areas. Gradually, rural dress began aligning more closely with urban styles, and regional distinctions in everyday wear diminished.

This homogenization worried many who felt that traditional ways were vanishing. That’s when a cultural movement began, aiming to preserve and revive what was perceived as “authentic” folk culture—complete with costume.

Folk Dress Revival: Identity and Nostalgia

Late 19th and early 20th centuries saw peasants ditching their regional dress for more standardized clothes as industrialization and migration changed societies. This loss triggered an identity crisis among urban elites and emerging middle classes. They saw the rural folk costumes as symbols of unique local heritage and national pride.

This led to a deliberate revival and sometimes an invention of folk costumes. Intellectuals, artists, and cultural committees collected examples of traditional dress and standardized them into neat, recognizable forms. These costumes were often worn for festivals and official ceremonies to celebrate “the spirit of the nation.”

Alterations, Simplifications, and Myth-Making

However, this revival wasn’t about slavish accuracy. Many costumes were simplified, altered for aesthetics, or universalized across entire countries or regions. Take Alsace, for example—the iconic starched white coiffe became a symbol of regional identity but originally was specific only to northern Alsace.

In Norway, Hulda Garborg’s 1903 documentation of folk dress highlighted diverse regional outfits but heavily favored some styles, culminating in the Hardanger area’s dress becoming a kind of unofficial national uniform. Similarly, Germany’s Tracht and Austria’s “dirndl” owe more to 1930s fashion elements than to authentic 19th-century peasant wear.

So, what we see at a Bavarian festival or a Scandinavian Midsummer may look “old-fashioned” but is often a deeply romanticized and modern version of the past.

What Does This Mean for You? Appreciating Folk Costumes Today

Now you know, folk costumes aren’t just clothes; they are living symbols weaving together history, culture, identity, and even some modern flair. Next time you see a group in traditional dress, remember that beneath those colorful aprons and intricate headpieces lies a complex story of real regional attire, evolving social habits, cultural pride, and sometimes political statements.

Want to explore further? Check out historical bookplates or visit museums showcasing rural life costumes—they offer fascinating insights. And if you ever wear or collect folk costumes, appreciate the stories sewn into every stitch.

In Short:

- European regions historically had unique local clothing styles, not uniform “costumes.”

- Historical records typically show best-dressed outfits, not everyday wear.

- Industrialization, urbanization, and fashion globalization reduced regional dress differences.

- Revival movements romanticized and standardized folk costumes for identity and culture.

- Modern folk dress often includes alterations, simplifications, and symbolic elements.

These costumes are part history, part invention, and all fun to explore. Who knew a wardrobe could hold so much meaning and mystery?