Pre-colonization Native Americans of the Midwest dealt with tornadoes through spiritual beliefs, oral traditions, practical adaptations, and respect for sacred sites, without written records directly documenting these storms. Their approach combined cultural interpretation, ritual practice, and environmental strategies to coexist with this powerful natural event.

Many tribes in the Midwest viewed tornadoes as living spirits or natural forces with intentions. The Kiowa tribe, for example, called tornadoes Mánkayía, describing them as great medicine horses or powerful horse-like spirits. A firsthand account from a Kiowa warrior named Iseeo describes encountering a tornado near the Washita River. In response, elders performed a ritual to calm the spirit: they lit their pipes, raised them respectfully toward the tornado, and asked the spirit to pass by without harm. The storm reportedly altered its course after these prayers, demonstrating how spiritual practice was central to their encounter with tornadoes.

Similar animistic views prevailed among different tribes. Some saw twisters and dust devils as negative entities, while others considered them sources of healing or teaching medicine. The Oglala Sioux, through the vision of Black Elk, portrayed thunderstorms as battles between Thunderbirds and water monsters. These symbolic narratives reflected the deep cultural integration of storm phenomena within tribal cosmologies and worldviews.

Since the concepts of written language were largely absent among most Midwest Native tribes, they preserved histories and knowledge about tornadoes through rich oral traditions. Tales, songs, and legends served as living records. For instance, the Shawnee named a frequently tornado-struck area near present-day Xenia, Ohio the “place of the devil wind,” based on oral history passed through generations.

Practical responses emerged alongside spiritual understandings. Tribes with migratory lifestyles adjusted their movements, avoiding regions prone to tornadoes during peak seasons. Architectural adaptations also helped communities withstand storm impacts. The Pawnee tribe constructed homes partially underground with rounded, dome-shaped roofs. This design minimized wind resistance, allowing tornadoes to often pass overhead without causing major damage. This contrasts sharply with modern housing, where flat walls and rooflines are vulnerable to wind uplift and destruction.

Other groups, especially those in hurricane-prone regions, used underground shelters to protect themselves and their food stores. Though these were not exclusive to the Midwest tribes, they illustrate a practical strategy toward violent weather applicable across Native cultures facing severe storms.

Specific legends highlight the sacred relationship between tribes and tornadoes. The Potawatomi tribe of Kansas revered Burnett’s Mound as a site guarded by powerful wind spirits. The tribe’s chief warned against disturbing the mound, believing it offered protection from storms. When the mound was altered in 1960 during construction, a massive F5 tornado struck Topeka six years later, causing destruction and loss of life. This story embodies the spiritual connection and respect for nature that influenced how Native Americans interpreted and coped with tornadoes.

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Cultural Interpretation | Spirits like Mánkayía (Kiowa), battles between Thunderbirds and water monsters (Oglala Sioux) |

| Oral Tradition | Storytelling, legends (Shawnee “devil wind” place, Potawatomi mound), no written records |

| Practical Adaptation | Seasonal migration, dome-shaped dwellings (Pawnee), underground shelters |

| Sacred Sites | Burnett’s Mound believed to protect from tornadoes; disturbance linked to devastating 1966 F5 storm |

Early European settlers and explorers later documented tornadoes in the Midwest through written accounts. While these do not represent Native records, they supplement oral histories.

- Tornadoes were mainly explained as living spirits or natural forces demanding respect and appeasement.

- Native Americans did not write about tornadoes but used detailed oral narratives and ceremonies to preserve knowledge.

- Housing styles and seasonal movement helped reduce tornado risks.

- Respect for sacred sites was important for spiritual and physical protection from storms.

- European pioneer writings added to the historical record of tornadoes in the region.

How Did Pre-Colonization Midwest Native Americans Deal with Tornadoes? Did They Write Records of These Storms?

Before European settlers arrived, Native American tribes in the Midwest faced tornadoes with a blend of spiritual reverence, practical wisdom, and storytelling, rather than written records. Tornadoes were not mere weather events — they were powerful spirits, forces to negotiate with, and lessons wrapped in danger.

So, how exactly did these communities handle tornadoes? And did they jot these terrifying winds down in journals? Let’s dive in.

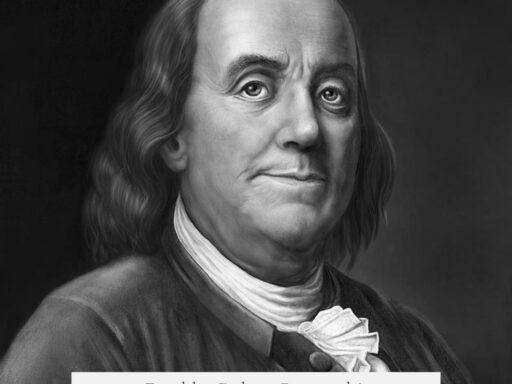

A Spiritual Dance with the Wind: Tornadoes as Spirits

Native Americans often personified tornadoes, seeing them as living entities with wills and intentions. When the Kiowa tribe called a tornado “Mánkayía,” they meant a great medicine horse — a spirit of horse-like power that thundered across the plains.

Imagine being Iseeo, a Kiowa warrior coming back from a raid near the Washita River. Suddenly, the ground trembles, and the sky lets out a roar like a herd of buffalo at mating season. You see a swirling red funnel tearing through timber — a sight both terrifying and awe-inspiring.

As young men panic, elders calmly light their pipes. They raise them high, praying and offering smoke to Mánkayía. The ritual isn’t just superstition—it’s a spiritual negotiation, an appeal for mercy and safe passage. Miraculously, the storm veers away.

This story, recorded in Mankaya and the Kiowa Indians: Survival, Myth and the Tornado, shows the deep respect and interaction these tribes had with tornadoes. It wasn’t about fighting the storm but making peace with it.

Other tribes shared similar beliefs:

- Many Native peoples saw tornadoes as living beings capable of reason.

- Southwestern tribes viewed these “twisters” mostly as negative spirits.

- Southeastern tribes saw tornado medicine as potentially healing or teaching.

Even Black Elk, the famous Oglala Sioux holy man, spoke of mighty thunderstorms in visions that tied natural forces to spiritual battles—Thunderbirds clashing with water monsters. These storms reflected eternal cosmic battles, reminding people of nature’s power and balance.

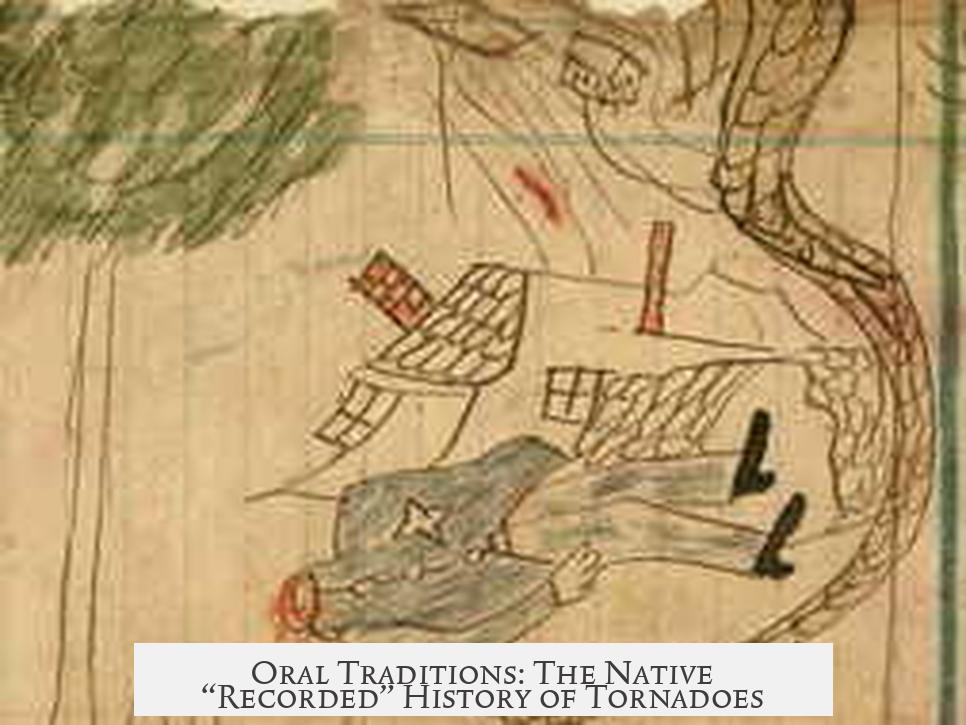

Oral Traditions: The Native “Recorded” History of Tornadoes

Did tribes write about tornadoes? No written manuscripts exist, as written language was generally unknown. But that didn’t mean tornado experiences vanished. They were etched in memory and passed down as rich stories and sacred teachings.

Take the Shawnee near Xenia, Ohio. Their oral history names certain tornado-prone areas as the “place of the devil wind.” This wasn’t just a nickname—it was wisdom, a warning handed down to avoid danger zones during certain times.

Think of it as an ancient weather app, powered by attentive storytelling.

Practical Smarts: How Tribes Adapted to Tornadoes

Spiritual respect aside, survival in tornado country demands practicality.

Weather Awareness and Migration

- Tribes on migratory routes adjusted their movements to avoid tornado season.

- Where you lived wasn’t random; it was often a strategic choice informed by decades of observation.

Shelter Construction

- The Pawnee Tribe built homes partially underground with rounded, dome-like shapes. This design minimized wind resistance, so tornadoes often simply passed over with minimal damage.

- In contrast, modern houses, with flat walls and edge-heavy roofs, practically invite roofs to become airborne frisbees during storms.

Underground Shelters on Islands

- Native groups living on hurricane-prone islands dug underground refuges to shield people and food from fierce storms.

These strategies reveal a clever combination of cultural respect, observational science, and engineering tailored to survive nature’s fury.

Legends and Historical Echoes: Storm Stories Beyond the Wind

Some legends serve as powerful reminders. The Potowatomi’s story around Burnett’s Mound in Kansas teaches respect for sacred places.

The mound was long guarded by strong wind spirits. The Potowatomi Chief Burnett warned against disturbing it.

In 1960, construction workers ignored this warning and disturbed Burnett’s Mound.

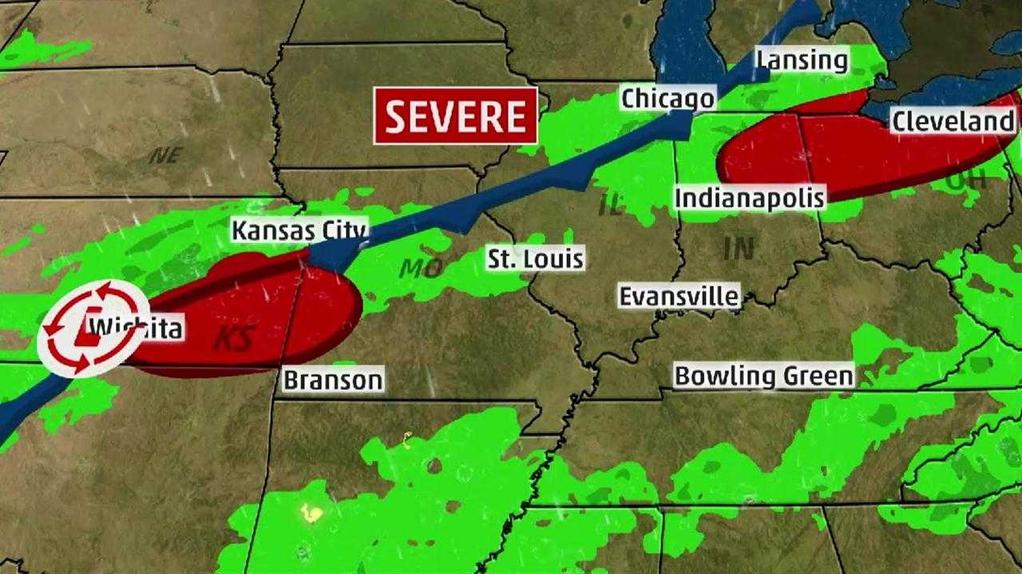

Six years later, Topeka faced an F5 tornado — half a mile wide, roaring with 300 mph winds for 34 minutes, destroying over 800 homes and killing 16 people.

The tribe sees the tornado as a cosmic warning—disturb the sacred, and you unleash chaos.

This legend tells us that respect for the environment and spiritual natural forces mattered deeply — and that ignoring these lessons can have real consequences.

European settlers and explorers, arriving later, documented tornadoes in written form, supplementing Native oral histories with early scientific-style records.

Wrapping It Up: The Full Picture

- Native Midwestern tribes saw tornadoes as powerful spirits that required respect and negotiation, not just fear.

- They used oral tradition and storytelling instead of written records to preserve their knowledge of these storms.

- Practical adaptations like seasonal migration and dome-shaped homes helped them live safely alongside tornadoes.

- Legends like Burnett’s Mound intertwine culture, spirituality, and nature to reinforce lessons on respect and survival.

- Written tornado records came later with settlers, but Native histories remain vital for understanding the full story.

Next time a tornado warning flashes across your screen, imagine the Kiowa elders calmly raising their pipes to the sky, negotiating with Mánkayía. Sometimes, survival isn’t just about dodging the storm — it’s about knowing how to respect and coexist with it.

Do you think today’s technology could learn a thing or two from these ancient weather wisdoms? Could storytelling be the missing link in modern climate resilience? Something to ponder as the winds blow.

How did Native American tribes in the Midwest interpret tornadoes before colonization?

Many tribes saw tornadoes as spirits. The Kiowa called them Mánkayía, a powerful horse-like spirit. Some believed tornadoes were living beings that could be reasoned with through rituals and prayers.

Did Midwest Native Americans write records about tornadoes?

Most tribes did not have written language and relied on oral traditions to record tornado knowledge. Stories, myths, and rituals passed down histories instead of written documents.

How did Native Americans protect themselves from tornadoes?

- They often moved seasonally to avoid tornado seasons.

- The Pawnee built dome-shaped homes partly underground to resist strong winds.

- Some groups used underground shelters for protection during storms.

What role did rituals play during tornado encounters?

Rituals like prayer and pipe ceremonies were used to calm or reason with storm spirits. For example, Kiowa elders would ask the tornado spirit to pass around their camp safely.

Are there specific legends linking tornadoes to sacred sites?

The Potowatomi believed Burnett’s Mound was guarded by wind spirits. Disturbing it was thought to invite destructive tornadoes, like the 1966 F5 tornado near Topeka.