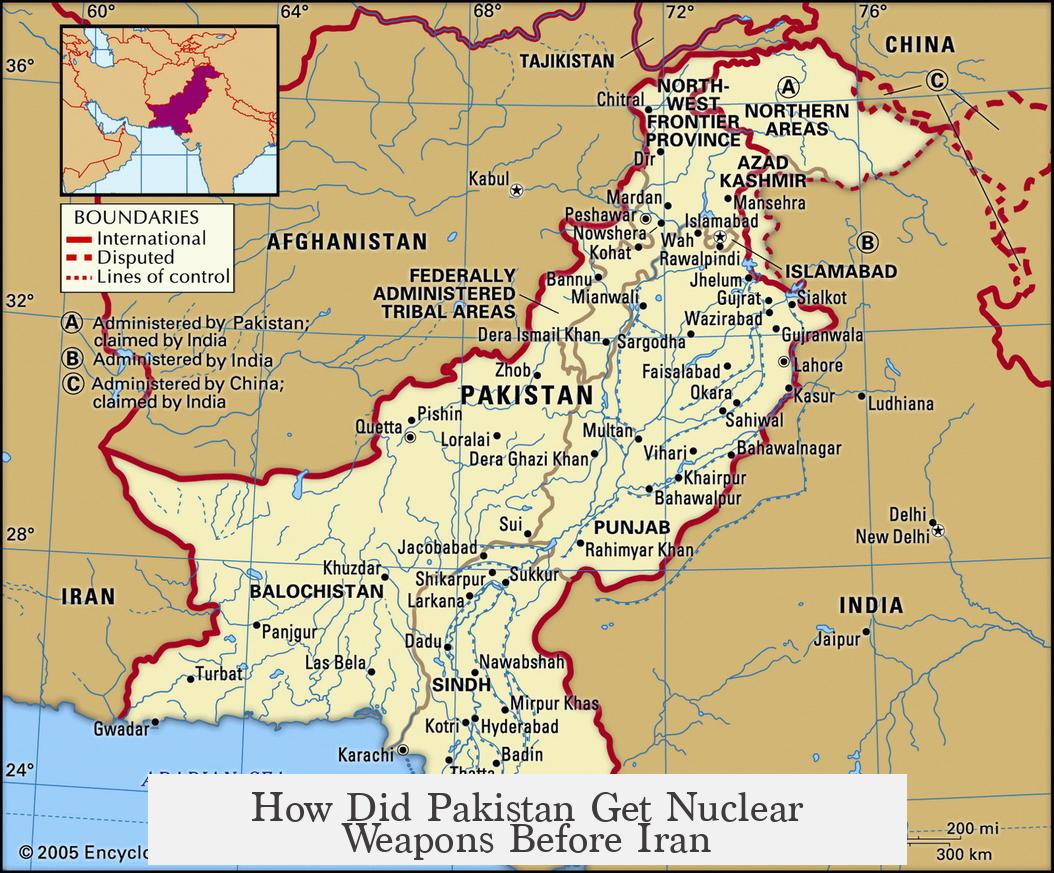

Pakistan obtained nuclear weapons before Iran due to a combination of earlier program initiation, geopolitical circumstances, external support, and differing international pressures. Pakistan began pursuing nuclear capability in the early 1970s, notably responding to India’s 1974 nuclear test. In contrast, Iran’s nuclear ambitions started earlier but shifted to weapons development much later, mainly in the 1990s and 2000s.

Pakistan’s program accelerated after India’s 1974 “Smiling Buddha” test. This made Pakistan prioritize nuclearization as a strategic necessity. It worked discreetly during the 1970s and 1980s, achieving weaponization by the late 1980s, though tests were public only in 1998.

Several factors helped Pakistan advance quickly:

- It received technical and material assistance from France and China. Both countries were outside the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) frameworks and served as crucial partners circumventing global restrictions.

- Pakistan exploited intelligence from nuclear facilities abroad, including espionage activities related to uranium enrichment technology.

- During the Soviet-Afghan war, Pakistan became a key US ally in countering Soviet forces. The United States tolerated some nuclear progress by Pakistan to maintain that alliance, limiting direct pressure on the program.

Conversely, Iran signed the NPT in 1970 and remained a member, limiting its ability to openly pursue nuclear weapons without international scrutiny. The 1979 Islamic Revolution and the Iran-Iraq war from 1980 to 1988 drained resources and delayed Iran’s nuclear advancements.

Skepticism persists about the exact timing of Iran’s decision to weaponize. Strong evidence suggests the shift occurred in the 1990s or early 2000s. The US’s aggressive policies toward Iran, including branding it part of the “Axis of Evil” and the 2003 invasion of Iraq, likely intensified Iran’s pursuit of nuclear weapons as a deterrent.

Although Iran received some technical help from Pakistan—particularly centrifuge technology—it faces considerable barriers:

- Unlike Pakistan, Iran has no significant alliance with the United States. This absence means less willingness by major powers to tolerate or ignore violations of its nuclear agreements.

- Being a signatory of the NPT, Iran is subject to intrusive inspections by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), dramatically increasing transparency.

- Iran’s nuclear infrastructure faces sabotage campaigns and targeted assassinations of scientists, mostly attributed to US and Israeli operations. This has slowed Iran’s progress significantly in ways Pakistan did not experience.

- The 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) further restricted Iran’s ability to develop weapons-oriented nuclear technology. Though the US withdrew from the deal in 2018, Iran only began gradually restoring some capabilities afterward.

The timeline advantage and geopolitical context are crucial:

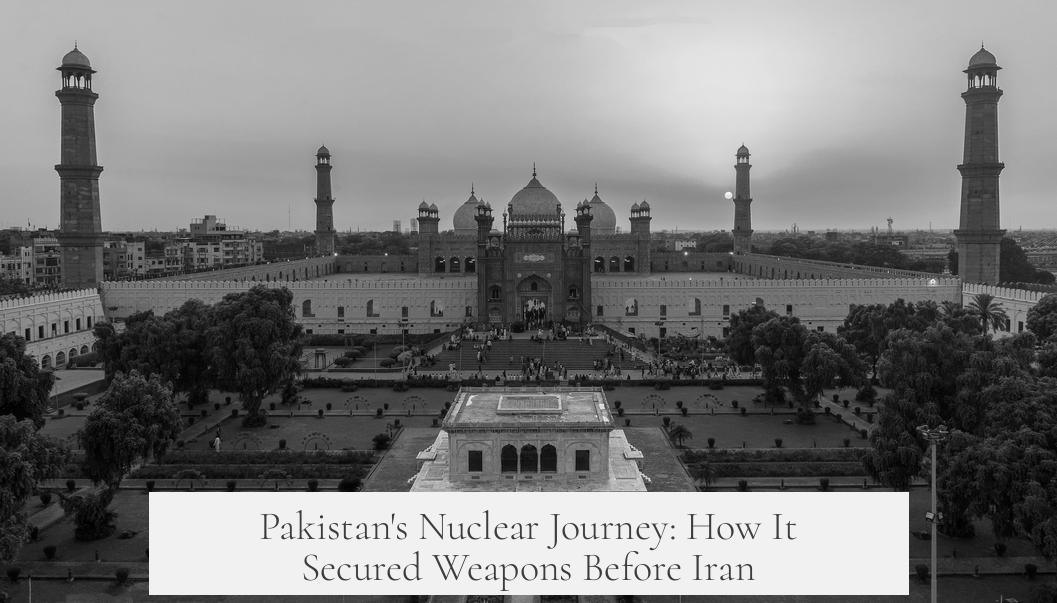

| Aspect | Pakistan | Iran |

|---|---|---|

| Start of Nuclear Program | Early 1970s (weaponization efforts intensified post-1974 India test) | Early 1970s (civilian) with weaponization shift in 1990s–2000s |

| Political Alignment | US ally during Soviet-Afghan War; benefited from tacit US acceptance | Adversary of US; closer to Russia; no US tolerance |

| NPT Status | Non-signatory (never joined the NPT) | Signatory; subject to IAEA inspections and restrictions |

| External Assistance | Received from France, China, plus espionage aids | Received Pakistani centrifuge tech; primarily indigenous development since |

| International Surveillance | Less scrutiny during Cold War era | High level of surveillance and sanctions; sabotage campaigns |

Pakistan’s nuclear strategy unfolded in a relatively permissive geopolitical environment, with Cold War dynamics shaping international responses. Iran’s program evolved under intense scrutiny and geopolitical isolation, compounded by US and Israeli opposition. These factors explain why Pakistan achieved an operational nuclear arsenal well before Iran.

Key takeaways:

- Pakistan started weaponizing in response to India’s 1974 test, achieving nuclear capability by the late 1980s.

- It benefited from external assistance and toleration by the US during the Afghan-Soviet conflict era.

- Iran’s pursuit faced resource constraints, was bound by NPT commitments, and encountered international inspections.

- Iran’s nuclear weapon efforts intensified only in the 1990s and 2000s under harsh sanctions and sabotage.

- Political alignment differences meant Pakistan had strategic allies aiding or ignoring developments, unlike Iran.

How Did Pakistan Get Nuclear Weapons Before Iran?

Simply put, Pakistan developed its nuclear weapons capability first because it started earlier, had crucial external help, and operated in a very different geopolitical landscape than Iran.

But that’s just the headline. Let’s unpack the story, because this saga involves political chess, secretive science, and a dash of international intrigue. Curious how a relatively poor country like Pakistan managed this feat long before Iran edged toward nuclear ambitions? Stay with me.

Starting the Countdown: Pakistan’s Nuclear Journey

Pakistan’s nuclear journey kicks off in the 1970s. Why then? A key incident shook things up: in 1974, India detonated its first nuclear bomb in a test dubbed “Smiling Buddha.” This was a big deal and lit a fire under Pakistan’s strategic planners. If the neighbor’s packing nukes, you’d better find a way to match or neutralize that threat.

Back then, Pakistan was economically struggling. Developing nukes is extremely expensive and complex. Plus, the world was rallying to prevent nuclear proliferation (enter the Non-Proliferation Treaty, or NPT). Pakistan was NOT a signatory. This meant: no official sanction or cooperation from the global nuclear order.

So, Pakistan had to get creative—fast.

The Secret Support: Who Helped Pakistan?

Pakistan found some surprising allies willing to quietly assist. Two nations stood out: France and China. Neither was bound by the NPT—and both had their own interests aligning with assisting Pakistan’s nuclear program.

- France contributed sensitive nuclear technology—even if officially it denied it.

- China provided missile technology and key nuclear know-how.

In addition to these overt and covert collaborations, Pakistan famously benefited from espionage. The most notable case: stealing details about uranium enrichment from URENCO, a Dutch consortium. This espionage shortcut helped Pakistan leapfrog certain technological hurdles.

The Geopolitical Wildcard: The Soviet-Afghan War

In the late 1970s and 1980s, Pakistan found itself a vital piece in a very different international puzzle—the Cold War’s proxy battleground in Afghanistan. The U.S., aiming to bog down the Soviets, heavily supported Pakistan’s intelligence network.

This alliance indirectly shielded Pakistan’s nuclear aspirations. The U.S. had little appetite to clamp down on Pakistan’s atomic progress while counting on it to fight Soviet influence. Washington essentially looked the other way on Islamabad’s nuclear activities—turning a blind eye for geopolitical convenience.

From Secret to Show: Pakistan’s Nuclear Test in 1998

All this culminated in Pakistan conducting nuclear tests in 1998, following India’s second round of tests the same year. These tests confirmed Pakistan’s status as a nuclear power—finally turning decades of silent work into international recognition.

Estimates suggest Pakistan had functional warheads possibly by the late 1980s, but it cautious little public disclosure until the tests. Covert development balanced with strategic patience was the game.

Iran’s Nuclear Story: A Slower, More Obstructed Road

Now, contrast Iran’s nuclear timeline with Pakistan’s. Iran joined the NPT in 1970, years before its Islamic Revolution in 1979. Unlike Pakistan, it agreed to the global nuclear rules framework, promising not to pursue weapons.

After the revolution, Iran’s priorities changed dramatically. A grueling war with Iraq (1980–1988) drained Iran’s resources and focus. Nuclear ambitions took a back seat to survival.

In the 1990s and 2000s, Iran’s intent seemed to shift more openly towards weaponization—perhaps partly as a defensive response to perceived U.S. hostility and threats following the “Axis of Evil” label and the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

Did Pakistan Help Iran? Yes, But Not Enough to Accelerate Rapid Development

Iran did buy some nuclear technology from Pakistan—particularly gas centrifuges for uranium enrichment. This kickstarted its indigenous program but did not translate into a fast-tracked pathway to weapons.

Complicating Iran’s progress: its status as an NPT signatory. This opened the door wide for international inspections and surveillance, making secret weapon-building a much harder task. Technologies for monitoring nuclear activities are far more advanced now than during the Pakistani nuclear escalation.

Political and Security Roadblocks for Iran

Unlike Pakistan, Iran never enjoyed tacit U.S. tolerance or indirect backing. It remained diplomatically isolated, with close ties to Russia rather than the West. This isolation meant heavy scrutiny and constant pressure.

Furthermore, Iran faced direct sabotage and covert operations—assassinations of nuclear scientists, cyber attacks like the Stuxnet virus, and other disruptions attributed to the U.S. and Israel. These tactics substantially slowed Iran’s development.

The Iran Nuclear Deal: A Halted Dance with Atomic Power

In 2015, Iran entered the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), an international agreement intended to curtail its nuclear weapons potential. This temporarily stalled Iran’s pathway to a bomb, limiting uranium enrichment and increasing inspections.

After the U.S. pulled out in 2018, Iran started to slowly restore some nuclear activities, stepping back toward dual-use capacities. But this cautious progress differs sharply from Pakistan’s unchecked and covert buildup decades earlier.

Putting It All Together: Why Pakistan Preceded Iran

| Factor | Pakistan | Iran |

|---|---|---|

| Start of Nuclear Program | 1970s, spurred post-India’s 1974 test | Early interest pre-1979, but slowed due to revolution and war; weaponization focus from 1990s onward |

| Foreign Assistance | France, China, plus espionage assistance | Some tech from Pakistan; limited external support |

| Political Alignment | U.S. ally in Afghan war; tacit U.S. tolerance | U.S. adversary; heavy Western surveillance and pressure |

| Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) Status | Not a signatory | Signatory, subject to inspections and constraints |

| Security Threats & Sabotage | Minimal sabotage; relatively secure environment | Persistent sabotage and assassinations |

So, What Can We Learn From This?

Pakistan’s nuclear success story is a mix of early start, strategic urgency, foreign help, and geopolitical coincidence—like the Soviet-Afghan War—that offered cover and incentives for Western powers to look the other way. Meanwhile, Iran’s path has been restricted by internal upheaval, war, diplomatic isolation, global treaties, and covert attacks.

The global landscape also changed dramatically from the 1970s to the 2000s. Today’s world has better nuclear surveillance and more pressure on nuclear ambitions, especially for nations under scrutiny. Iran’s slow progress reflects these modern realities.

Final Thoughts

In the nuclear chess game of South Asia and the Middle East, timing and alliances matter—big time.

Pakistan’s early and covert start—alongside a realpolitik world willing to turn a blind eye in the name of larger goals—gave it a clear edge. Iran faces a more constrained, watched, and contested environment.

If nuclear weapons possession were a race, Pakistan’s head start and friendly escort helped it cross the finish line well before Iran even hit the track.

What do you think? Could Iran’s nuclear ambitions catch up, or will political and technological barriers keep them at bay? Drop a thought below!