Average British people generally handled the mid-20th century decline of their empire and global dominance with indifference and pragmatism, shifting focus from imperial pride to domestic concerns and cultural influence.

The contraction of the British Empire passed mostly unnoticed by ordinary citizens. Despite the empire’s vast scale, its decline rarely stirred strong opinions or widespread anxiety among everyday Britons. The empire was something distant rather than a pressing reality in daily life. Even family connections abroad or military service in colonial territories did not translate into deep emotional engagement.

Historically, the empire held little cultural significance for the general public. British literature from the empire’s zenith, including works by Jane Austen and Charles Dickens, contains few imperial themes, reflecting limited popular interest. The empire remained largely peripheral to most people’s identity and concerns.

Post-World War II realities helped explain this outlook. British society was exhausted after the war and eager to focus inward. This change showed clearly in the 1945 general election. Winston Churchill’s Conservative government, strongly linked to imperial maintenance, lost to Clement Attlee’s Labour Party, which pushed welfare reforms and decolonization.

The Attlee government prioritized granting independence to colonies, beginning with India in 1947, while establishing the National Health Service. This political shift symbolized a broader societal desire to move away from costly imperial commitments. Many citizens supported this transition, or at least accepted it without resistance.

Britain’s approach to decolonization stood in contrast to other imperial powers. Unlike the French, who fought fiercely to keep Algeria, British leaders and their public displayed pragmatism and even enthusiasm for ending colonial rule. Political debates over Indian Independence were largely civil and focused on practical concerns rather than nationalist outrage.

While hard political and military power diminished, Britain’s cultural influence persisted strongly. British pop culture, music, and film flourished internationally, fostering a sense of pride and global presence despite territorial losses. The global impact of the Beatles and the cultural image projected by James Bond exemplify how Britain maintained soft power in the post-imperial era.

This cultural leadership reassured many Britons. It showed that Britain’s influence had not disappeared but transformed. Elements of British civilization—representative democracy, liberal values, free market capitalism, and the English language—continued to shape global society. British sports like football, rugby, and cricket became international phenomena, symbolizing the spread of British culture across former colonies and beyond.

Many Britons viewed the rise of the United States as a natural extension, rather than a replacement, of British global leadership. The US inherited much of its political framework and culture from Britain. This kinship between English-speaking peoples made it easier for British citizens to accept the shift in world power without feeling abandoned.

The persistence of British cultural and legal systems worldwide reassured ordinary people that their nation’s legacy endured. This helped frame the loss of political empire as a transition from hard power to soft power dominance, allowing many to perceive decline not as defeat but as evolution.

| Aspect | Public Attitude | Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Empire Decline Awareness | Limited attention or concern | Empire seen as distant and abstract |

| Cultural Relevance | Minimal impact on daily life or identity | Little emotional investment in empire |

| Post-WWII Mood | War fatigue and desire for welfare | Shift toward domestic priorities |

| Decolonization | Pragmatic acceptance | Peaceful transition of colonies |

| Soft Power | Strong cultural influence globally | Enduring British presence worldwide |

| Relationship with USA | Seen as natural successor | Reduced psychological impact of decline |

In sum, the average Briton did not experience the empire’s decline as a crisis. Lack of cultural attachment and war exhaustion shifted public focus. Political changes reflected popular desires to build a welfare state rather than maintain imperial power. British society largely accepted decolonization, maintained cultural leadership, and embraced Anglo-American kinship.

- The public remained largely indifferent to empire loss, seeing it as distant.

- Post-war fatigue redirected attention from empire to welfare and domestic issues.

- Decolonization occurred peacefully with broad societal support.

- British cultural influence and global legacy persisted strongly.

- The United States’ rise softened the blow of imperial decline for many Britons.

How Did Average British People Handle the Decline of Their Empire and World Hegemony in the Mid-20th Century?

Contrary to what history books and dramatic documentaries might suggest, the average British person during the mid-20th century hardly erupted in collective grief or outrage as their empire contracted and world dominance faded. Many were either indifferent or simply accepted it as a natural shift, focusing on domestic concerns rather than clinging to fading imperial glory.

This somewhat unexpected reaction invites a closer look into how the British public digested this profound geopolitical change. What happened in the hearts and minds of everyday citizens? And why didn’t the empire’s decline dominate national conversations? Let’s unpack this history with a little humor and plenty of detail.

First off, imagine watching your favorite TV channel suddenly shrink the number of episodes of your favorite show—but instead of drama, most viewers just flipped channels. The British Empire’s fall was kind of like that for many Britons. They noticed, sure, but it wasn’t a gripping soap opera to obsess over.

1. General Indifference: “Empire? What Empire?”

The average person’s reaction was marked by indifference. Despite what looks like an explosive loss of global power on paper, most Britons barely registered it. Why? Because, for many, the empire was distant. It might have been spoken about in classrooms or newspapers, but it wasn’t shoved into everyday concerns or social chit-chat.

That huge colonial expanse? To many, it was an abstract concept, a bit like reading about astronauts on Mars today—not irrelevant, but certainly not cause for immediate emotional investment.

2. Empire’s Minimal Cultural Weight: Jane Austen and Dickens Didn’t Bother

Here’s a striking fact: during the empire’s heyday, major British literary figures like Jane Austen and Charles Dickens barely touched imperial themes in their writing. This reveals just how little the empire permeated popular culture and the private thoughts of Brits.

So, if epic authors of the time were casually unconcerned with empire matters, why would the common folk fret over it? For many, it was simply not a lens through which they viewed their lives or futures. The empire existed “out there,” not inside British living rooms or pubs.

3. After the Blitz: Priorities Shift to Homefront Rebuilding

World War II was a game changer. The British were exhausted—both physically and emotionally. Winning the war didn’t feel like a cue to maintain global dominance. Instead, the post-war election in 1945 saw Churchill’s Tory government, synonymous with imperial pride, replaced by Labour’s Clement Attlee, whose focus landed on social reforms like the National Health Service.

In a nutshell, the electorate said: “Thanks for winning us the war, Winston, but now let’s fix our own backyard.” The empire’s fate fell low on the list of concerns, overshadowed by housing, health, and welfare.

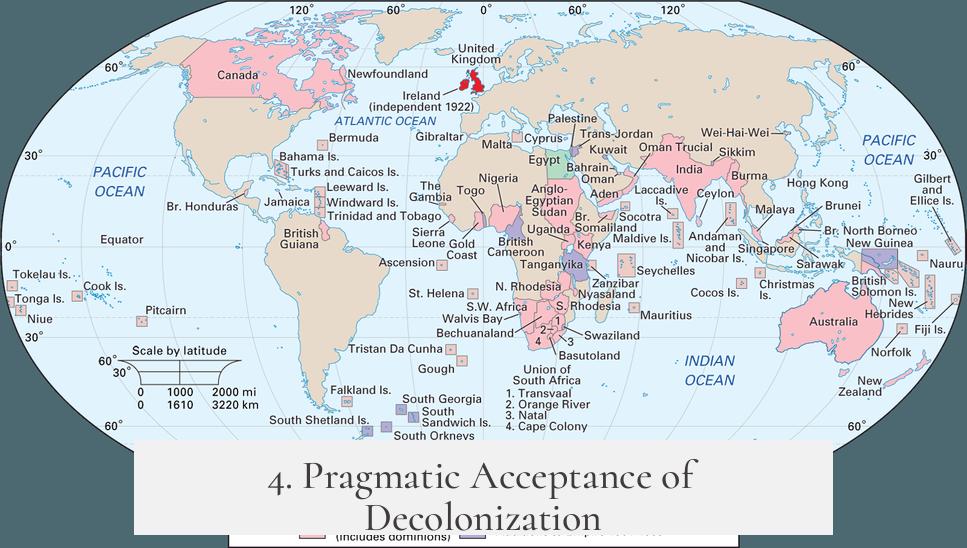

4. Pragmatic Acceptance of Decolonization

Unlike France, which fought tooth and nail over Algeria, Britain’s political and public response to decolonization was surprisingly pragmatic. When India gained independence in 1947, Attlee faced criticism—but mainly civil debate, not widespread public upheaval.

The British were almost enthusiastic, or at least resigned, helping smooth the handover process. This acceptance contrasts sharply with other imperial powers, suggesting many Britons saw empire decline as a rational evolution, not a catastrophe.

5. Cultural Legacy: The Beatles and James Bond to the Rescue

Military might faded, but British cultural power soared. While tanks and battleships lost their shine, British films, music, fashion, and literature filled global airwaves and theatres. The Beatles’ rise was seismic—kids around the world plugged into British pop culture, proudly waving the Union Jack.

Meanwhile, James Bond—our suave spy—became a symbol of enduring British cool and sophistication. His cinematic escapades masked a subtle message: Britain still held sway, even if its empire didn’t.

6. Britain’s Civilizational Footprint: The Empire’s Quiet Echoes

British influence lived on through its civilizational elements—democracy, legal systems, English language, sports, and free-market capitalism. The English Common Law became a global standard. Sports like football, rugby, and cricket spread across former colonies, weaving British cultural threads into new national fabrics.

Such enduring legacies reframed imperial decline from a hard loss to a soft, continuing power. This cultural emphasis helped cushion the psychological blow for many, offering a sense of participation in a global “British” tradition.

7. The USA: The Empire’s Heir Apparent

For many Britons, the rise of the United States as the new global superpower offered reassurance. The USA was essentially “British foreign policy made in America”—sharing language, political structure, legal principles, and even ethnic roots.

This kinship made the empire’s decline feel like a polite passing of the torch within an extended family, rather than a humiliating defeat. Britain’s role morphed from ruler to elder statesman of an Anglophone alliance.

8. Sports: The Empire’s Everyday Global Legacy

Think about Brazil’s obsession with football, or India’s love for cricket. These weren’t just imported pastimes; they became national identities. Imagine telling a British person in 1925 that one day, South Africa and New Zealand would passionately play rugby, and countries worldwide would cherish British sports. They’d be baffled.

Yet, this global diffusion of British sports symbolized a cultural imperial footprint thriving even after political empire declined. It gave many Britons a tangible way to feel proud of their heritage amid widespread change.

So, What Does This All Mean for the Average British Experience?

The British empire’s decline wasn’t an emotional earthquake for most citizens. It was more like watching a tide ebb—noticed but not feared as catastrophic. Priorities shifted toward rebuilding the nation, improving social welfare, and embracing new forms of influence.

This served a practical purpose. Instead of clinging to distant colonies and global policing, British people largely pivoted toward creating a modern welfare state, celebrating cultural exports, and nurturing friendly ties with the rising American superpower.

It’s a story less of bitter loss and more of pragmatic adjustment. The empire’s contraction was seen less as an end and more as a transformation of British identity—from ruler of vast lands to cultural influencer and global partner.

Final Thoughts: How Would the Average Brit Today Reflect on That Era?

Imagine a Brit from the 1950s explaining to a modern audience how the empire shrank. They might shrug and say, “The world changes. We just stopped fussing about faraway places and started taking care of our mates back home.”

British society’s resilience lies partly in its ability to embrace this change without a collective trauma performance. Instead of pining for empire past, Brits found pride in soft power achievements, democratic values, and cultural legacies that still ripple worldwide.

In short, the empire’s decline wasn’t their drama; it was background noise while they rewired their national story—and, as it turns out, wrote some pretty good chapters in popular music.

| Key Aspect | Average British Reaction |

|---|---|

| Empire Decline Awareness | Largely indifferent or unengaged |

| Cultural Connection to Empire | Minimal emotional or intellectual engagement |

| Post-WWII Political Shift | From imperialism to welfare state prioritization |

| Decolonization | Pragmatic, relatively peaceful acceptance |

| Shift to Soft Power | Dominance in music, film, fashion |

| Civilizational Influence | Continued global impact through law, language, sport |

| United States Succession | Accepted kinship eased transition |

| Sports Legacy | Global adoption of British origin sports |

To wrap up, the average British person handled the empire’s decline with a mix of indifference, pragmatism, and cultural pride, focusing on internal improvements rather than global losses. They turned a page quietly, focusing on what they could control and what still made them proud.

1. How aware were average British people of the empire’s decline in the mid-20th century?

Most ordinary Britons showed little concern about the empire’s shrinking. The collapse of British power was largely unnoticed in daily life. It did not spark widespread public debate or emotional response.

2. Did British culture reflect strong ties to the empire during its decline?

No, the empire held minimal cultural importance for average people. Even famous British authors during the empire’s peak barely mentioned imperial themes. This suggests that the empire was not central to British identity then.

3. How did post-war politics affect British attitudes toward the empire?

After WWII, war-weariness made Britons favor domestic issues over imperial ambitions. The 1945 Labour victory marked a shift toward welfare and decolonization, signaling acceptance of empire’s end rather than resistance.

4. Was there significant opposition among Britons to decolonization?

Generally, the British public accepted granting independence to colonies with pragmatism. This contrasted with other colonial powers like France, where withdrawal faced violent resistance.

5. In what ways did Britain maintain global influence after losing its empire?

British cultural products like music, literature, and film gained global popularity. Figures such as The Beatles and James Bond embodied a shift from military to cultural power, softening the impact of Britain’s imperial loss.

6. How did the rise of the United States affect British perceptions of their empire’s decline?

Many saw the U.S. as a natural successor due to shared Anglo cultural and political roots. This made it easier for Britons to accept the end of their empire, viewing American dominance as a continuation of British influence.