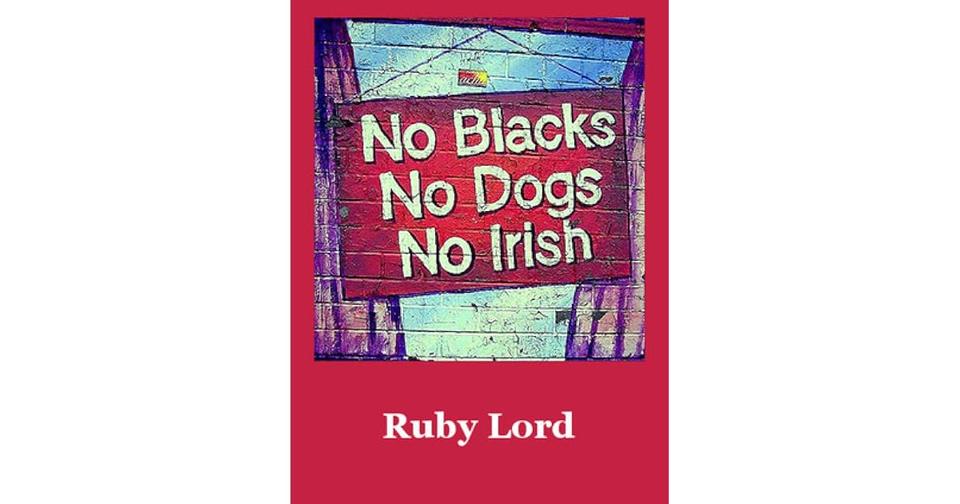

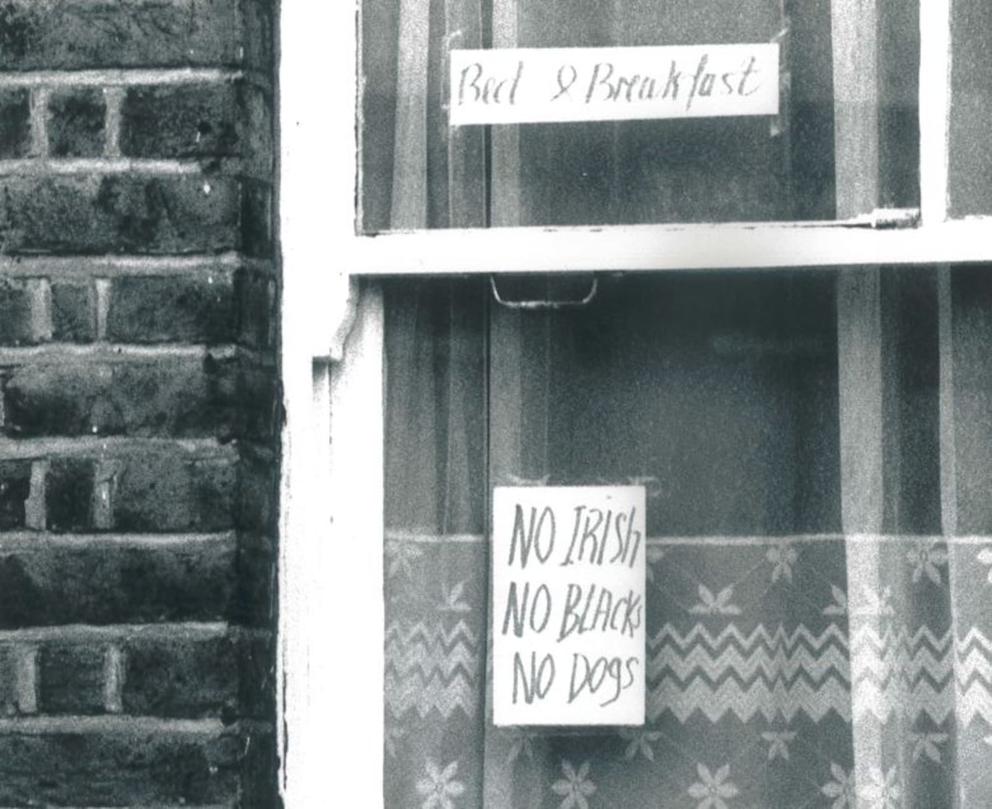

“No Blacks No Dogs No Irish” signs were present and documented in the UK, particularly in the post-war period of the 1950s, marking explicit housing discrimination against Black and Irish communities. While these signs were not universally widespread, they were more than isolated instances and serve as powerful symbols within the collective memory of immigrant experiences. These notices reflected broader systemic discrimination rather than the sole method of exclusion faced by these groups.

These signs appeared primarily in urban centers such as London (notably in areas like Stepney and Brixton), Birmingham, and Manchester. Scholars in race relations and sociology have recorded such explicit statements on housing listings excluding ‘coloured’ tenants and Irish migrants. For example, a sociologist noted that in parts of Birmingham and Manchester, landlords openly declared “no coloured; no Irish,” fearing these groups would “lower the tone of the neighbourhood” and reduce property values.

Irish historian Enda Delaney explored the frequency of these signs and confirmed that they were “not uncommon” during the 1950s. They occupy a significant place in Irish migrants’ collective memory in Britain and commonly emerge in personal testimonies about post-war settlement difficulties. The phrase has also influenced popular culture, such as in the autobiography of John Lydon, whose Irish parents raised him amidst such discrimination.

However, researchers caution that these narratives, while emblematic, can sometimes blend communal memory with individual experience. Despite this, the existence of such signs in the UK is not seriously contested as it is in some historical contexts abroad, notably the United States. Over time, terminology on signs evolved: “coloured” was widely used before becoming recognized as offensive in later decades.

It is important to understand these signs within the larger context of systemic housing discrimination. The signs acted as visible markers of wider exclusionary practices by landlords and social authorities. For instance:

- Council housing was theoretically race-neutral but had long waiting lists that disproportionately impacted immigrant groups.

- Available housing often failed to meet tenants’ needs related to size and affordability.

- Private landlords frequently denied Irish tenants to appease neighbours’ prejudices, often justified by stereotypes about Irish habits or conditions, such as living in crowded lodgings.

These forms of discrimination reflect social tensions and economic hardship rather than concrete cultural traits of immigrants. Irish migrants faced ambivalent racialization in Britain. Initially, they were perceived as racially inferior and associated with poverty. Yet, the arrival of Black migrants from Commonwealth countries shifted public perception. Irish migrants began to be categorized as “white” over time, reducing their visible racial otherness. The once paired phrase “No blacks no Irish” gradually dissolved into separate forms of exclusion, with hostility focusing more sharply on Black immigrants.

Sociologist Sheila Patterson noted that in Brixton, landlords described Irish migrants with similar derogatory terms to those used for Black tenants but viewed Irish tenants as somewhat more acceptable because their ethnicity was less visually apparent. Neighbours could not easily object to Irish migrants as they could to visibly distinct minorities.

Institutional policies mirrored these shifts. The British government granted Irish migrants free entry rights, recognizing their racial similarity to Britons. In contrast, Black Commonwealth migrants faced immigration quotas soon after. Such distinctions cemented the differentiated treatment of immigrant groups in social and legal terms.

By the 1960s, the Irish immigrant population’s visibility diminished in official records. For instance, many health sector administrators stopped counting Irish nurses as immigrants, focusing the term “overseas nurse” mainly on nurses of color. This reflects both changing immigration patterns and evolving perceptions.

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Geographic Presence | London (Stepney, Brixton), Birmingham, Manchester |

| Time Period | Primarily 1950s post-war era |

| Nature of Signs | Explicit exclusion of Blacks and Irish in housing adverts |

| Symbolism | Markers of broader housing discrimination and social exclusion |

| Shift in Perception | Irish migrants moved from racialized outsiders to ‘white’ status by 1960s |

| Official Policy | Free right of entry for Irish; quotas for Black Commonwealth migrants |

In sum, “No Blacks No Dogs No Irish” signs undeniably existed in the UK, particularly during the 1950s housing market turmoil faced by migrant groups. These signs were more than isolated acts but less widespread than collective memory might imply. They symbolized an entrenched system of discrimination that affected Irish and Black migrants distinctly. Over time, public attitudes and legal policies evolved, granting Irish migrants greater acceptance as part of a broad societal shift.

- Signs appeared in major UK cities during the 1950s, explicitly barring Black and Irish tenants.

- These signs represent broader systemic housing discrimination rather than the sole barrier faced.

- Irish migrants transitioned from racialized outsiders to part of the white majority over time.

- Official immigration policies favored Irish migrants compared to Black Commonwealth arrivals.

- The legacy of these signs remains strong in migrant collective memory and cultural expressions.

How Common Were “No Blacks No Dogs No Irish” Signs in the UK? Exploring Reality Behind the Phrase

Yes, signs stating “No Blacks No Dogs No Irish” did exist in the UK, particularly during the 1950s, but they weren’t simply casual garden-variety notices; they embodied a harsh reality of housing discrimination faced by immigrants, notably Irish and black communities. These signs were more than mere words—they stood as symbols of prejudice woven into the fabric of Britain’s postwar society.

But how widespread were these signs really? What do they tell us about Britain’s social climate then, and how did the Irish experience compare to other groups? Let’s unpack this tangled history with care, uncovering facts that reach beyond that infamous slogan.

The Signs Were Real, But Their Frequency Varied

Race relations scholars have documented the existence of these exclusionary notices in immigrant-heavy areas like London’s Stepney and Brixton, as well as in Birmingham and Manchester. These signs often read explicitly “No coloured; no Irish” when offering accommodations, leaving no ambiguity about who was unwelcome.

“In some districts…it is not uncommon to find notices offering accommodation that specify ‘no coloured; no Irish’. There is a strongly held impression that these groups…will ‘lower the tone of the neighbourhood’ and…‘bring down property values.’” [2]

This tells us the signs did appear regularly in some neighborhoods, echoing a clear societal bias. The phrase penetrated enough that it entered the collective memory and cultural references, such as in the autobiography of John Lydon, known as Johnny Rotten, whose Irish parentage shaped his experiences and artistic voice.

Memory and Myth: Were These Signs Everywhere?

Irish historian Enda Delaney examines the nature and frequency of these signs deeply. While acknowledging that they were “apparently not uncommon sights in the 1950s,” he urges caution before considering these signs everywhere and all the time.

“No blacks, no Irish” signs occupy a central place in the collective memory of the Irish in Britain but oral histories can blend well-known communal memories with personal life stories.” [3]

We have to pause here. Collective memory is powerful but sometimes amplifies rare events into dominant narratives. The signs certainly existed, but they were part of a broader, systemic problem rather than isolated or ubiquitous postings on every street corner.

The Signs Symbolized Larger Patterns of Housing Discrimination

Owning a “No Blacks No Dogs No Irish” sign did not capture the full scope of exclusion experienced by Irish and black migrants. Much discrimination occurred in subtler, harder-to-prove ways.

One example: council housing waiting lists were long for everyone, but immigrant families, particularly Irish, were hit harder by shortages and unsuitable housing conditions. Private landlords, wary of neighborly complaints, would often reject Irish tenants, citing stereotypes about their living standards rather than any genuine cultural behaviors.

“It’s more likely that the signs have come to stand in for the more insidious forms of discrimination… landlords and ladies turned away Irish applicants because ‘the neighbors might object,’ often based on stereotypes… crowded lodging houses, which had nothing to do with ‘Irish culture’ but everything to do with the fact they couldn’t rent elsewhere.”

So, while a landlord might not openly advertise a discrimination sign today, the effect was the same — a cold shoulder based on race or nationality.

Irish Status Shifted as New Immigrant Groups Arrived

One fascinating twist in this story is the changing racialization of the Irish in Britain. Initially racialized as “poor and inferior,” the Irish shared the brunt of discrimination with black migrants.

But as more black migrants arrived from the Commonwealth, societal focus shifted. The Irish became increasingly perceived as “white,” leading to a decline in their association with exclusionary signs. The infamous slogan “no blacks no Irish” slowly unraveled, reflecting evolving racial dynamics.

“The arrival of black migrants from the Commonwealth drew attention away from the Irish. As hostility towards black migrants increased, the Irish became deracialized and assimilated into the category of ‘white’… the grouping of ‘no blacks no Irish’ became ungrouped.” [4]

This racial “upgrade,” though a mixed blessing tied to the painful hierarchy of racism, meant that Irish immigrants gradually escaped some visible forms of prejudice within housing and social policies.

Legal and Institutional Nuances: Irish Privilege Compared to Black Migrants

British immigration policies also reflected this complex social hierarchy. Irish migrants were granted free entry into Britain, their race politically identified as the same as that of the British population. This status was “earned” despite negative stereotypes because of what policymakers called “arguments of commonsense” and the “outstanding fact” of their whiteness.

Conversely, black migrants faced entry quotas and more barriers to settlement. These legal distinctions reinforced social boundaries sharply.

“British policymakers regarded Irish migrants as an ‘unpredictable and inconsequent people’, but worthy of continued access… by virtue of their race.” [5]

This institutional recognition didn’t erase racism but shaped how it was enacted in law and daily life.

The Fading Visibility of Irish Immigrants Post-1960s

By the 1960s, Irish migrants’ visibility as a distinct immigrant group faded. Their presence remained strong in sectors like healthcare — notably nursing — but officials began to exclude Irish workers from immigrant statistics.

This statistical invisibility marked a social shift: the Irish were now “inside” the British fold in ways black and other ethnic minorities were not.

“Many administrators stopped counting Irish nurses as immigrants at all. The term ‘overseas nurse’ became shorthand primarily for nurses of color—even though Irish nurses’ experiences were shaped by their Irishness.” [6]

So the sign phrase itself faded from daily life, even as underlying discrimination patterns morphed and continued toward others.

Key Takeaways and Reflections

- “No Blacks No Dogs No Irish” signs did exist. They were documented in several UK cities, notably in the 1950s housing market.

- They symbolized broader, less visible discrimination. The signs represent blatant exclusion but also serve as symbols of widespread prejudice including denial of housing access and social alienation.

- The signs may not have been everywhere. Collective memory may amplify their frequency beyond reality, but their impact was profound for those affected.

- The Irish experienced racialization that shifted over time. Initially stigmatized similarly to black migrants, they later assimilated into the “white” majority, reshaping British racial politics.

- Institutional policies favored Irish migrants. They were legally privileged in immigration policy compared to black Commonwealth migrants.

- The visibility of Irish migrants declined by the 1960s. Subsequent histories and official data made Irish immigrants more “invisible,” changing narratives around immigrant status and identity.

So, How Common Were These Signs, Really?

They were certainly not a universal feature of every British street, but the existence of these signs reflects significant real discrimination in several urban centers. Significantly, they embody the visible tip of an iceberg of exclusion and hostility Irish and black migrants faced. Many people remember these signs vividly, shaping cultural understandings and informing generations about the harshness of integration.

Have you ever wondered how communities recover from such overt exclusion? The Irish story shows a complicated journey from exclusion to reluctant acceptance, shaped by shifting racial hierarchies and changing social attitudes. It reminds us that discrimination wears many masks—some obvious, some invisible.

Understanding these signs helps us confront the uncomfortable truths of Britain’s postwar history and the legacies still echoing today. It is a story worth remembering, beyond the slogan.