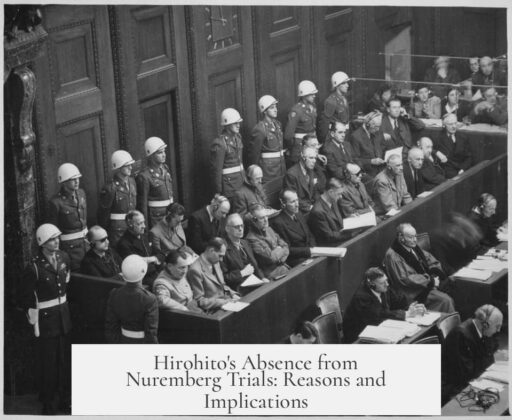

Hirohito was not charged at the Nuremberg Trials due to a deliberate decision by the Allied powers, particularly the United States, to protect his position and use his influence to stabilize post-war Japan. The Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP), led by General Douglas MacArthur, prioritized safeguarding the emperor. MacArthur believed Hirohito’s cooperation was essential for a peaceful occupation and to prevent resistance from the Japanese population.

Hirohito held a unique role throughout World War II. Although he was Japan’s sovereign, the full extent of his involvement in military decisions remains debated. The Allied prosecutors faced a dilemma: charging Hirohito would undermine efforts to rebuild Japan and might incite unrest during occupation.

During the Tokyo Trials, the prosecution’s narrative portrayed the war as the result of aggressive militarists hijacking Japanese governance. This allowed the Allies to isolate blame on key figures, such as Prime Minister Tojo Hideki. Tojo’s testimony even initially implicated Hirohito but was toned down following a recess requested by American prosecutors. This move underscored the priority placed on protecting the emperor’s image.

This narrative benefited both sides. Japan’s public could accept the war’s cause as the work of a militaristic minority rather than the emperor or its people broadly. The U.S., wielding dominant influence over Japan’s occupation, found it easier to establish legitimacy and facilitate reconstruction with the emperor as a symbolic figurehead remaining in place.

The choice not to prosecute Hirohito was a pragmatic strategy rather than an oversight. It recognized the emperor’s potential to promote stability in occupied Japan. Prosecuting him risked delegitimizing the government and provoking widespread opposition, which could derail all efforts toward peace and recovery.

| Reason | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Political Pragmatism | U.S. needed Hirohito to maintain order in occupied Japan. |

| MacArthur’s Priority | General highly valued emperor’s role and protected him. |

| Legal Narrative | Blamed militarists to isolate responsibility and facilitate occupation. |

| Public Stability | Kept emperor to pacify Japanese populace and legitimize reforms. |

- Hirohito’s power was unique but complex, making prosecution risky.

- The U.S. prioritized occupation success over full legal accountability.

- Protecting Hirohito allowed smoother Allied control in Japan.

- The Tokyo Trials focused on military leaders, not the emperor.

How Come Hirohito Was Not Charged at the Nuremberg Trials?

Emperor Hirohito was not charged at the Nuremberg Trials because the Allied leadership, especially the Americans under Douglas MacArthur, believed prosecuting him would hurt the postwar occupation and reconstruction of Japan. They saw him as a crucial figure to maintain order and facilitate Japan’s transition from wartime enemy to peaceful ally.

This decision has sparked curiosity and debate for decades. Why was the one person who held supreme power in Japan left untouched by justice?

The Problematic Position of Emperor Hirohito

Emperor Hirohito occupied a unique spot in history. He wasn’t just a symbolic figurehead; technically, he wielded immense authority throughout World War II. The Allied powers, when planning the Tokyo Trials, aimed to show a conspiracy of Japan’s government to wage aggressive war. Yet, the trouble was—Hirohito was at the top, with the actual power to stop it all.

How do you prosecute a man who, theoretically, could have ended the war but didn’t? That was a huge dilemma. Despite this, he was not prosecuted. The narrative of “militarists hijacking the government” was simpler. But this sidestepped Hirohito’s actual involvement.

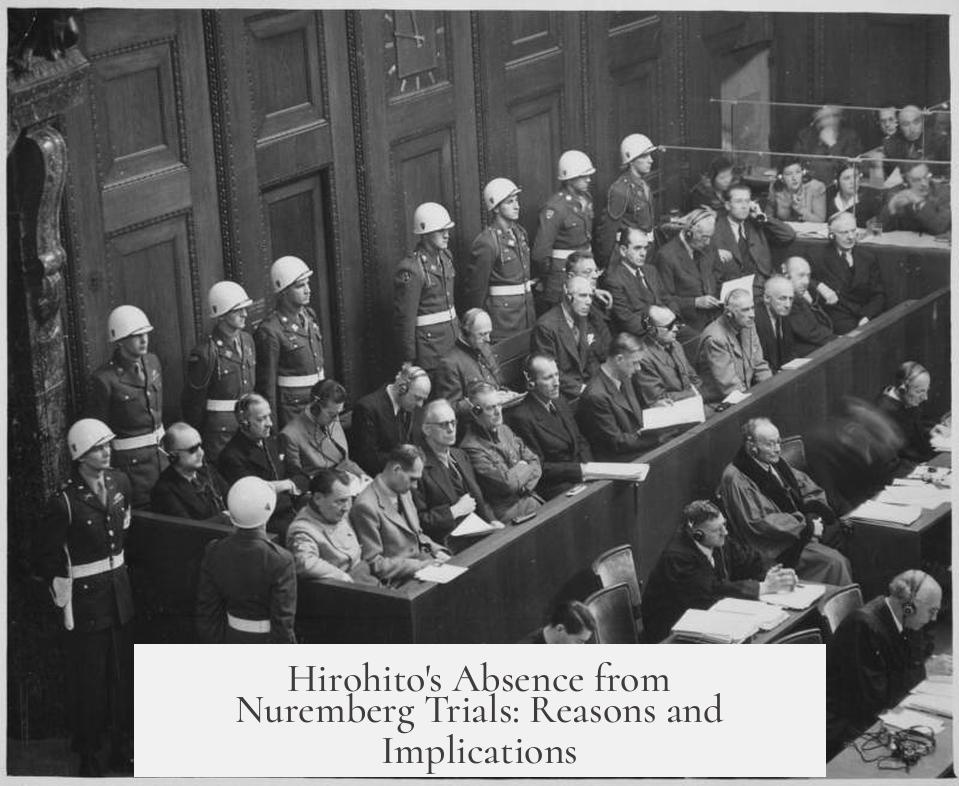

SCAP’s Strategic Protection of Emperor Hirohito

Enter SCAP—the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers. This was the office held by General Douglas MacArthur, a man who shaped post-war Japan’s fate. MacArthur had his reasons for shielding Hirohito.

First, it was practical. The Americans believed Hirohito could help pacify Japanese resistance during occupation. Removing him risked unrest or rebellion in a fragile society barely recovering from war’s devastation. MacArthur’s priority? Keep the Emperor as a symbol of continuity and stability.

MacArthur reportedly admired Hirohito in a way that surprised many historians. His awe was so strong that protecting Hirohito became “number one” on his agenda.

Even when Tojo Hideki, Japan’s former Prime Minister and Army Minister, inadvertently implicated Hirohito during testimony, the American prosecutors reined it in. Tojo had said, essentially, that the army couldn’t have acted without the Emperor’s consent. The Americans called a recess and had Tojo amend his statement to avoid trouble for Hirohito. This illustrates just how far they went to shield him.

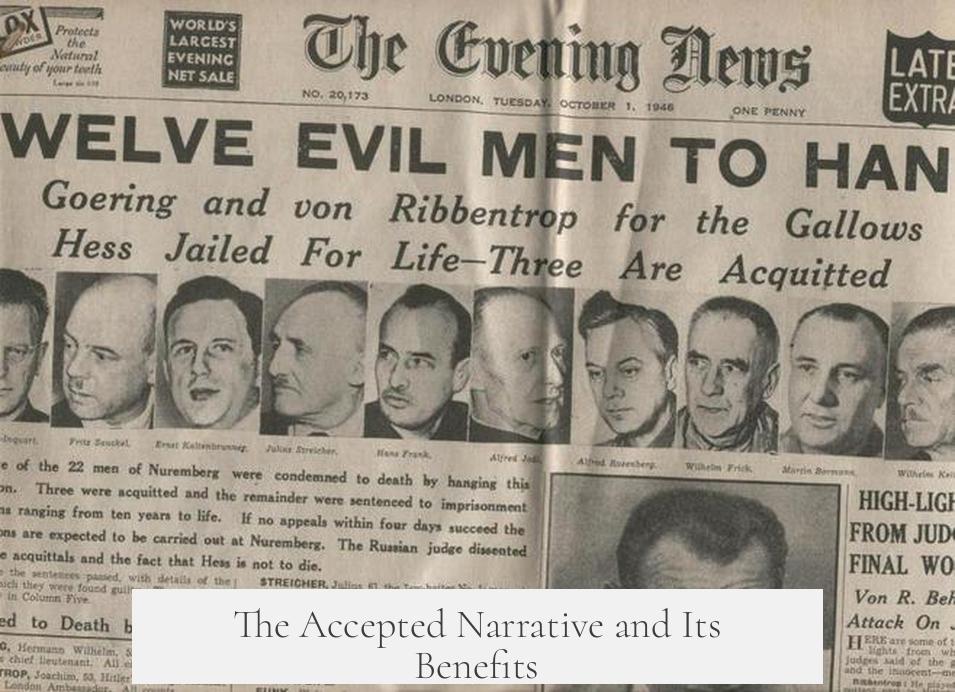

The Accepted Narrative and Its Benefits

The narrative that stuck goes like this: militarists seized Japan’s government, pushed aggressive war policies, and dragged the nation to the brink. Hirohito was conveniently outside this blame loop, seen as a detached emperor rather than a war criminal.

Why was this narrative welcomed?

- For Japan, it deflected the vast guilt from the masses and the Emperor himself to a select few leaders like Tojo. This helped the population face defeat without collective shame.

- For the Americans, it smoothed over the occupation process. By keeping Hirohito as a sovereign figurehead, they granted legitimacy to their reforms and control without provoking Japanese backlash. Essentially, the Emperor was “rehabilitated” to help rebuild a peaceful Japan allied to the West.

The Pragmatic Reason for Not Prosecuting Hirohito

At the end of the day, the reason boils down to pragmatism. The Americans judged that prosecuting Hirohito would be counterproductive.

Imagine trying to govern a defeated enemy while purging their revered emperor. Chaos might have ensued. Instead, they chose to use Hirohito as a tool—a bridge between Japan’s imperial past and its democratic future under occupation.

But Was This Just?

That’s the million-dollar question historians still debate. Was shielding Hirohito a necessary evil or a miscarriage of justice?

On one hand, his wartime authority and silence during Japan’s aggressive campaigns imply responsibility. On the other, occupying powers prioritized stability and reconstruction over punitive justice in his case.

It also poses questions about victor’s justice and the limits of international law. How far should accountability go when political realities intervene?

Lessons and Reflections

This story vividly shows how political motives shape history as much as facts do. Pragmatism, not pure justice, often drives decisions in the aftermath of conflicts.

If you wonder how powerful leaders escape prosecution, Hirohito’s case provides a stark example. He was a linchpin in Japan’s social order, deemed too valuable for peace to prosecute.

Maybe it’s a lesson in complexity—justice in international politics isn’t always black and white. Sometimes it’s a calculated choice.

Summary Table: Hirohito and the Nuremberg Trials

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Position in WWII | Supreme ruler with power to influence Japan’s war policies |

| SCAP Leadership | Douglas MacArthur prioritized his protection to maintain order |

| Prosecution Narrative | Militarists blamed for aggressive war; Emperor set aside |

| Legal Action | No charges against Hirohito to avoid unrest and facilitate occupation |

| Implications | Justice compromised for political stability; debate continues |

So, next time you wonder why Hirohito escaped the Nuremberg spotlight, remember it wasn’t because he was innocent. It was a complex, strategic decision shaped by occupation needs, political calculations, and the goal of Japan’s peaceful transformation.

After all, history isn’t always about what’s right or wrong. Sometimes, it’s about what works.