Workhouses were harsh institutions designed to deter poverty through strict discipline and poor conditions, but their reality was complex. While widely feared and criticized for cruelty and neglect, some workhouses offered marginal improvements over destitution outside, though they often inflicted psychological harm and failed to address root problems effectively.

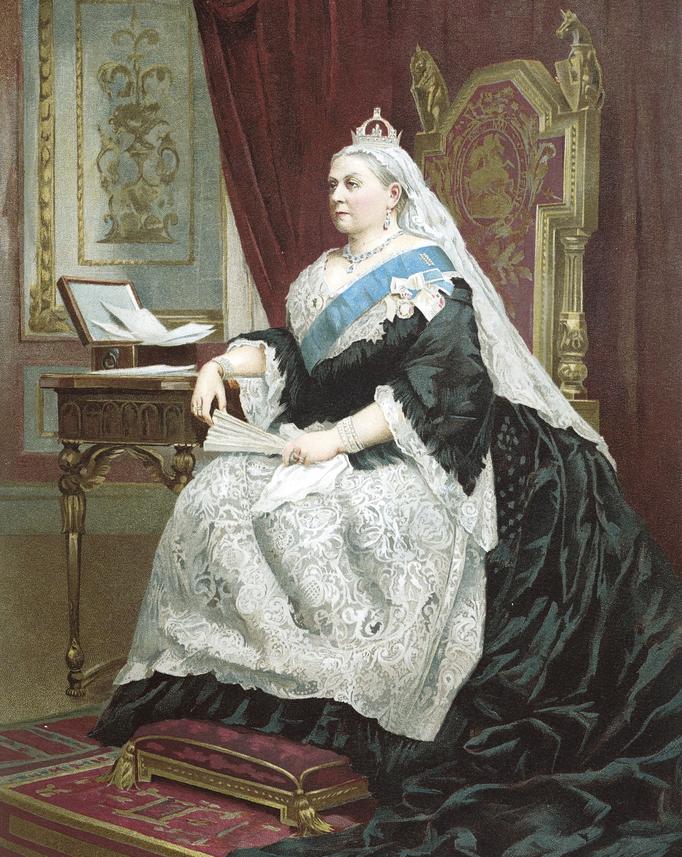

The origins of workhouses trace back to the Poor Law of 1601 under Elizabeth I. Back then, local parishes typically provided relief via the church, helping the deserving poor such as the elderly and disabled. Able-bodied people were expected to work, often being sent to a designated place where they received materials for labor like iron for forging or hemp for ropemaking. However, purpose-built workhouses were uncommon at this stage.

In the 18th century, population growth increased poverty, pushing parishes to combine resources and build Union Workhouses. These institutions housed the homeless, orphans, insane, and elderly who lacked family support. Parishes still recognized some people deserved alms, but the able-bodied poor were required to work.

The 1834 Poor Law Reform marked a brutal shift. Influenced by Jeremy Bentham’s utilitarian philosophy, new Union Workhouses imposed compulsory labor for all inmates. To discourage dependence, conditions were intentionally made repellent. Charles Dickens’ depictions of such places, especially the Scrooge-endorsed model, fueled public disdain. The workhouse was not just a refuge but a deterrent—designed to be as unpleasant as possible to prevent reliance.

Despite these aims, harsh realities generated scandals. Medical experts in the mid-19th century highlighted how concentrating large numbers of ill elderly in one place spread diseases like tuberculosis. Mortality rates in many workhouses were alarmingly high. Underfunding and neglect worsened conditions. Notoriously, in the Andover workhouse, hunger drove inmates to gnaw on bones they were tasked with breaking for fertilizer. At Huddersfield, there was an account of a living patient sharing a bed with a corpse for an extended period. These extremes showcased institutional failure and cruelty.

Some reforms attempted to improve conditions. Laws prevented separating families and parents from children. Modest improvements in living standards emerged. Still, the work demanded remained menial and ineffective, such as unraveling old ropes to produce oakum for ship caulking. Forcing elderly or disabled individuals into such tasks was cruel and financially wasteful.

Leaving the workhouse was possible, but difficult. Able-bodied inmates had to give notice days in advance. Jack London’s experience in a London workhouse in 1902 revealed its futility. While he was allowed to seek work outside, managers resented it. London found widespread under-employment and severe poverty outside, with many holding jobs that did not prevent homelessness. To him, workhouses were unpleasant and pointless but not the absolute worst of poverty.

Experiences varied widely among workhouses. Some provided steady meals, rudimentary education, and basic medical care—improvements for many poor children and elderly compared to street life. Food types depended on locally grown crops; some even had orchards. Inmates undertook different forms of labor depending on location—oakum picking, stone breaking, garden work, among others.

Psychologically, the workhouse carried a heavy stigma. Entering one symbolized failure, igniting dread and intense desire to avoid it. The fear extended beyond physical conditions, hitting inmates’ sense of self-worth. This was a powerful social deterrent more than the actual living conditions themselves in some cases. Despite some benefits, the compulsory workhouse system inflicted lasting harm through social humiliation.

| Aspect | Reality |

|---|---|

| Purpose | Provide relief but deter poverty via harsh conditions and compulsory work |

| Conditions | Poor, often unsanitary, overcrowded, and disease-ridden |

| Work | Menial, repetitive, often cruel to elderly/disabled, low economic value |

| Living Standards | Varied; some had steady food, basic medical care, and education for children |

| Psychological Impact | Dread, stigma, humiliation, sense of failure for the poor |

| Scandals | Neglect, starvation, sharing beds with corpses, disease outbreaks |

- Workhouses evolved from early aid systems but became deliberately harsh after 1834 to deter reliance.

- Many suffered from neglect, disease, and menial labor, but experiences varied widely.

- Some workhouses provided minimal education, steady food, and shelter, sometimes improving on street poverty.

- Psychological harm and social stigma around workhouses were severe, creating intense fear among the poor.

- Despite intentions, workhouses failed to reduce poverty effectively and often worsened inmates’ physical and mental well-being.

How Bad Were Workhouses Really? Taking a Closer Look Beyond the Horror Stories

So, how bad were workhouses really? The short answer: they were grim and harsh, but not always the absolute horrors history paints them to be. Many factors affected experiences inside, and while conditions were often appalling, some workhouses offered essentials better than the outside poverty most faced. Let’s dig into the gritty details.

Workhouses have a reputation as cruel places where the poor were punished, starved, and forced to do pointless labor. Thanks to Dickens and later accounts, we picture them as bleak prisons of misery. But history suggests the picture might be more nuanced.

From Elizabethan Beggars to Victorian Unions: The Origins and Purpose

The idea of workhouses didn’t just pop up with Victorian England. The Poor Law of 1601 tried to tackle the problem of unemployed “sturdy beggars” by setting able-bodied poor to work, supplying basic materials like iron for forging or hemp for rope. But actual workhouses were rare.

Back then, local churches often handled relief. This was somewhat unconditional because in tight-knit communities, people knew who truly needed help versus who might just be a shirker.

Fast forward to the 18th century—population growth and urbanization created more poverty than isolated parishes could handle alone. Wealthier parishes combined to build Union Workhouses. These were meant not only for the able-bodied forced to work but also as shelter for widows, orphans, the elderly, and even the mentally ill.

Then Jeremy Bentham shook things up. His brutal ethical ideas shaped the 1834 Poor Law Reform, transforming workhouses into places deliberately made horrible to discourage entry. The motto was: make it worse than the worst poverty outside.

The Darker Side: Problems and Scandals

The reformers’ theory backfired in many ways.

| Issue | Details |

|---|---|

| Health and Mortality | Grouping many elderly and sick people in one place spread deadly diseases like tuberculosis. Mortality rates soared. |

| Funding and Neglect | Bare bones budgets led to shocking neglect. In Andover, inmates resorted to gnawing on bones intended for fertilizer. Huddersfield allowed a dead patient to share a bed with a living one. You wish this was a bad joke. |

These stories shocked Victorian society, but they were symptoms of a system more interested in deterrence than care.

Reforms and the Limits of ‘Work’

Eventually, some reforms eased the harshest rules. Splitting families was banned. Some basic medical care arrived, and conditions marginally improved.

But the labor was often menial and pointless. Oakum picking—pulling apart old ropes—was a hallmark task. It was backbreaking, especially for the elderly with arthritis. It brought in little value and frankly, was cruel.

Interestingly, people could leave the workhouse with a short notice. Yet this rarely helped escape poverty. Jack London’s 1902 time in a London workhouse reveals this: managers protested when he wanted to look for work outside instead of wasting his days picking rope.

What did London see outside? Millions underemployed or in low-wage jobs, sleeping on the streets. To him, workhouses were awful but logically, no worse than life for many poor people.

Not All Workhouses Were Created Equal

Did all workhouses suck the same? Nope.

“Some Victorian workhouses were actually a step up from life outside.”

Not kidding. Imagine, regular meals. For kids, basic schooling and skills training. A little medical treatment. In some workhouses, residents ate the crops grown on site, ensuring a steady supply and reducing costs. A few even had orchards!

George Orwell, writing decades later, showed these differences persisted. Tasks, meals, and conditions varied widely. Some inmates did stone-breaking or other more arduous labor. Others stuck with oakum.

But here’s the kicker: regardless of actual conditions, workhouses evoked dread. They symbolized failure and disgrace. Being forced inside was seen as losing your last shred of independence.

What Can We Take Away? Workhouses Were Bad, But Not Absolutely Horrible

- The original aim of workhouses was to provide an organized place for those who could not sustain themselves.

- Bentham’s extreme deterrence logic reshaped them to be intentionally repellent, which bred neglect and neglect bred suffering.

- Health risks and scandals show the dark side—sometimes horrific neglect.

- Reforms helped, but labor was often pointless and cruel.

- Outside poverty was brutal, too. For some, workhouses offered better food and shelter than the streets.

- Experiences varied a lot by location, management, and individual circumstances.

- The psychological impact of stigma and dread was powerful, shaping much of their terrible reputation.

Closing Thought: How Should We Judge Workhouses Now?

History loves black-and-white judgments, but workhouses were more gray than pitch-dark. A lot depended on where you lived and what you experienced inside.

They were *designed* to be harsh enough to scare able-bodied poor away, but humane reasons—like sheltering children or elderly—sometimes softened practices.

What’s clear: they weren’t nice. But they also weren’t always as nightmarish as popular culture claims. Often, they reflected a society struggling to manage widespread poverty with limited compassion.

So the next time someone gasps about “how bad workhouses were,” tell them the truth. They were bad, yes. But bad in different ways, hard, messily designed, and sometimes oddly better than the desperate poverty beyond their walls.

And maybe imagine yourself having to pick rope or smash bones—ouch. That’ll make you thankful you’re reading this comfortably at home rather than stuck inside one.

What was the original purpose of workhouses?

Workhouses aimed to provide work for the able-bodied poor. They also sheltered vulnerable groups like widows, orphans, and the disabled. Early efforts focused on local relief, before larger union workhouses were created.

Why were conditions in workhouses considered harsh after 1834?

The 1834 Reform made workhouses deliberately tough to deter people from entering. Everyone had to work, and conditions became unpleasant, often overcrowded and poorly funded.

Did all workhouses have the same conditions?

No, conditions varied widely. Some had better food and basic medical care. Tasks also differed, including oakum picking or stone breaking depending on the location and local resources.

How did workhouses affect physical health?

Grouping many sick and elderly people caused high disease rates, such as tuberculosis. Mortality in workhouses was often high due to overcrowding and neglect.

Were workhouses an effective way to fight poverty?

Workhouses offered menial work with little real benefit. Many inmates left to find jobs elsewhere, showing the system failed to solve poverty effectively.

Why did people fear going to the workhouse?

The workhouse symbolized failure and social stigma. Fear was as much psychological as physical, creating dread around the idea of entering one.