Vodou acquired its evil reputation primarily due to colonial-era prejudices, misinterpretations by Haitian elites, sensationalist foreign reporting, and notable crimes linked to the religion, culminating in official anti-Vodou campaigns.

During the colonial period, authorities and European settlers saw Vodou as dangerous witchcraft. This view stemmed from a lack of understanding combined with colonial fears of African cultural practices that seemed foreign and threatening. European-educated Haitian elites, influenced by Eurocentric ideas, generally dismissed Vodou as backward and superstitious, which further entrenched negative perceptions. They internalized prejudices about Africa as a continent of fanaticism and savagery, associating Vodou practices with obstacles to modernization and civilization.

Many Haitian elites tolerated Vodou but framed it as mere entertainment—music, dancing, and feasting—tainted by negative acts like alcoholism, hysteria, and animal sacrifice rituals. This dismissiveness reflected a broader European disdain and mirrored the French belief in a “civilizing mission,” wherein local traditions were seen as inferior. Their disdain masked the religion’s role as a key part of Haitian cultural identity and resistance.

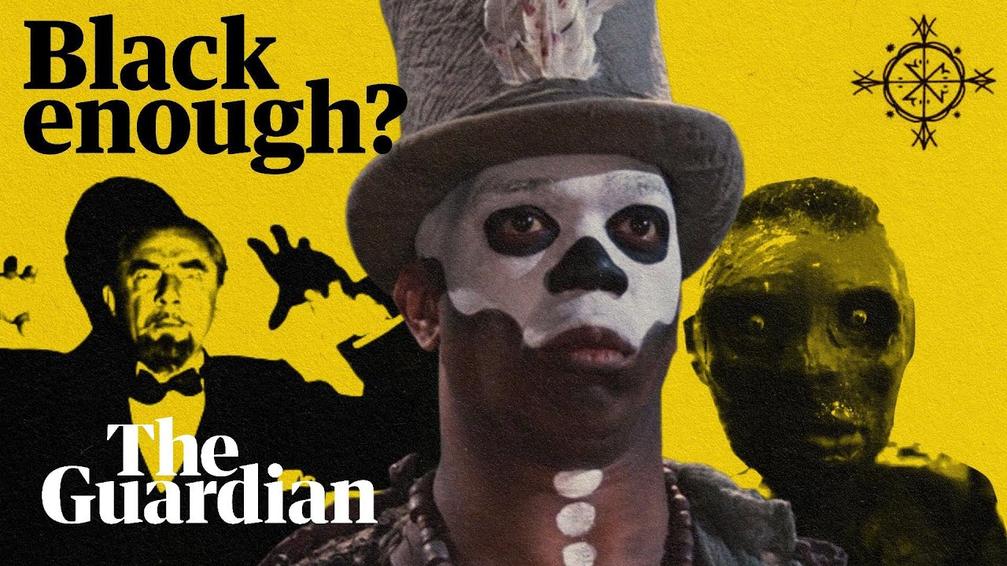

Foreign observers, especially in Europe and America, reinforced these views. Since Haiti’s independence after the Haitian Revolution, the media ridiculed the new nation and used Vodou as proof that Black people could not govern themselves. This narrative served to justify slavery’s continuation abroad and later European colonization efforts in Africa. Vodou’s connection to African roots made it a symbol of barbarism and backwardness in these accounts.

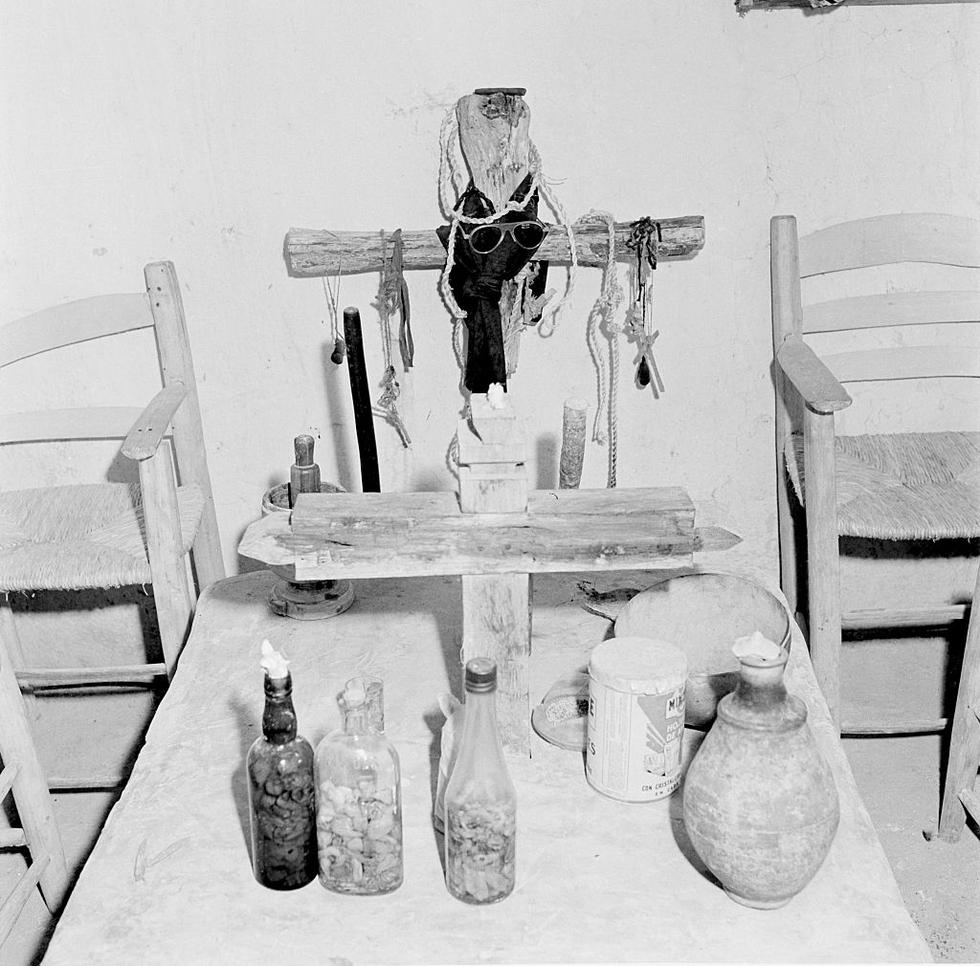

In 1797, Moreau de Saint-Méry, a French slave-owner, described Vodou extensively. He warned about its potent influence, recounting instances where even White observers were compelled to dance involuntarily and had to pay to be released from its power. Though he did not claim Vodou involved cannibalism or human sacrifice, he focused on the sex rituals and blood sacrifices, presenting the religion as a dangerous form of social control.

Visibility of Vodou in political life further impacted its reputation. For example, in 1850, Emperor Faustin Soulouque publicly performed Vodou ceremonies involving animal sacrifices. The French press reported this event, criticizing Haiti as regressing into savagery. Their portrayal emphasized Vodou’s “African” and “savage” aspects, framing the religion as primitive and unsuitable for a modern state.

Mid-19th-century European writers viewed Vodou as bizarre, part secret society and part religious ritual, tinged with witchcraft and loose morality. While they saw it as barbaric, they stopped short of declaring it evil, seeing it more as strange and exotic.

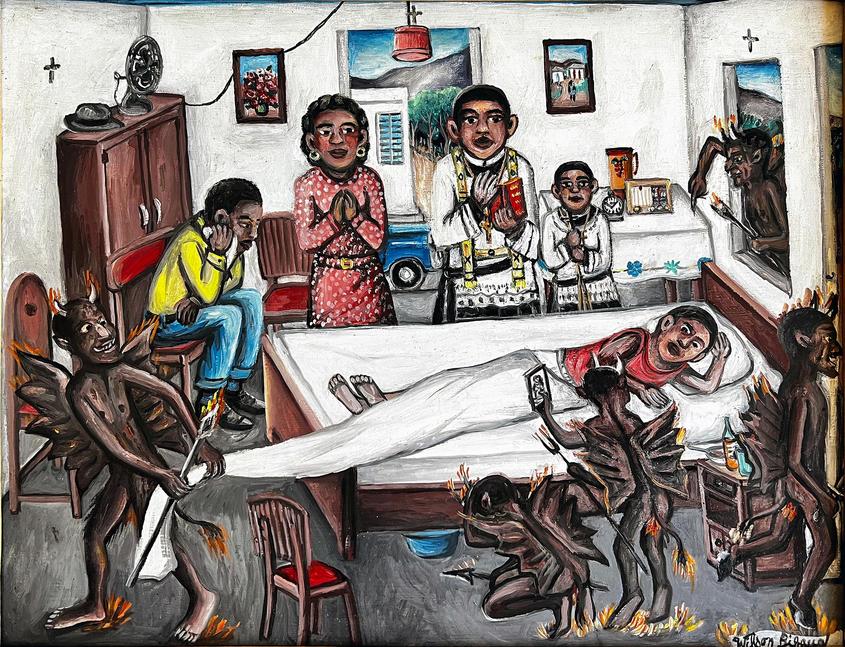

A turning point was the 1863 Bizoton affair, which linked Vodou to a horrific crime. Two Vodou practitioners kidnapped and murdered a child as a human sacrifice, then took part in a cannibalistic feast. The event shocked public opinion. Haitian newspapers and courts gave the crime widespread coverage, and the perpetrators were executed. This case cemented the association of Vodou with violence, superstition, and evil in the public eye both in Haiti and abroad.

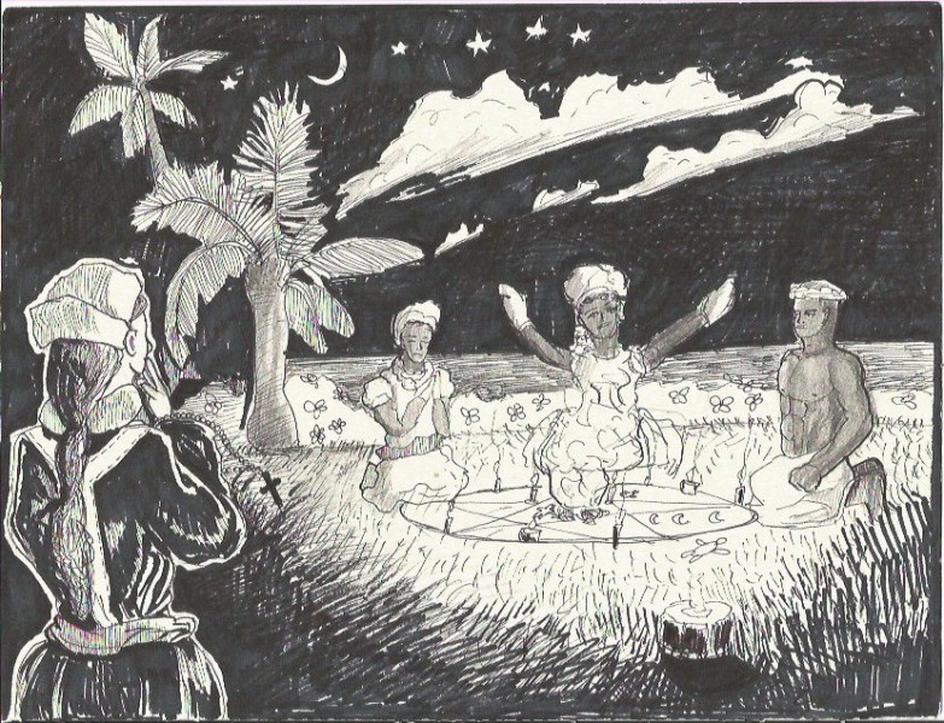

The Bizoton trial gave Catholic authorities the opportunity to campaign against Vodou aggressively. After President Geffrard signed a concordat with the Vatican in 1860, a new French clergy arrived to enforce Catholic orthodoxy. The church-led campaigns framed Vodou as a devil cult, an African impurity needing eradication. These campaigns included anti-witchcraft drives into the 20th century, portraying Vodou as a threat to morality and social order.

Several recurring themes explain Vodou’s bad reputation:

- Colonial Fear and Control: Colonizers portrayed Vodou as witchcraft to justify domination.

- Class and Racial Prejudice: Educated elites rejected Vodou to distance themselves from African heritage.

- Sensational Reporting: Foreign media focused on blood rituals, animal sacrifices, and alleged immorality.

- Political Instrumentalization: Vodou’s portrayal reinforced racist justifications for slavery and colonization.

- Extreme Cases: Crimes like the Bizoton affair reinforced the notion of Vodou’s evil aspects.

- Religious Opposition: Catholic campaigns actively sought to demonize and eradicate Vodou.

These forces combined to shape a long-lasting stigma. Today, scholarly efforts seek to understand Vodou as a complex, syncretic religion rooted in Haitian history and spirituality. Despite ongoing stereotypes, the religion remains a vibrant cultural force, often misunderstood due to its violent and sensationalized portrayals recorded in history.

| Factor | Description |

|---|---|

| Colonial Perception | Seen as witchcraft, dangerous and uncivilized |

| Haitian Elites | Dismissive, internalized European racism |

| Foreign Media | Mockery and sensationalism |

| Bizoton Affair | Child sacrifice linked to Vodou; major scandal |

| Church Campaigns | Anti-Vodou drives tied to Catholicism |

Vodou’s negative reputation results from a blend of misunderstandings, fear, racism, and political agendas rather than the religion’s true beliefs or practices.

- Colonial powers branded Vodou as dangerous paganism to control populations.

- Haitian elites often distanced themselves from African roots to appear civilized.

- Foreign press exaggerated Vodou’s exotic and violent elements.

- High-profile crimes linked to Vodou increased fear and public condemnation.

- Catholic authorities promoted anti-Vodou campaigns as moral cleanses.

How and Why Did Vodou (‘Voodoo’) Acquire Its Evil Reputation?

The short answer: Vodou earned its spooky rep mainly because of colonial fears, elite dismissal, wild reports of rituals, sensational crimes, and political agendas ready to paint it black.

Let’s dive deeper. Vodou, often spelled “Voodoo” in popular culture, started as a profound spiritual system rooted in African traditions brought by enslaved peoples to Haiti. Yet, throughout history, it became tangled in a messy web of fear, misunderstanding, and politics. Why? Because those in power—both in Haiti and abroad—wanted it that way.

Here’s the story behind the myth.

Colonial Fears and Haitian Elite Attitudes

During colonial times, European authorities eyed Vodou with suspicion. They categorized it as dangerous witchcraft, a threat to colonial control. Why? Because it was deeply tied to African heritage—a culture they had long demonized. Vodou wasn’t just a religion; it was a cultural act of defiance and survival.

Fast-forward to the 1920s and 1930s, and the scene inside Haiti itself wasn’t much better. Many Haitian elites, educated in European ways, looked down on Vodou as backward and uncivilized. They shared European prejudices that painted Africa—and by extension, Vodou—as fanatical and wild. Such elites clung to the belief in Europe’s “civilizing mission.”

One elite might say, “Vodou? Oh, it’s just a bunch of fun and games—music, dance, and food. But unfortunately, it also involves animal sacrifices and wild hysteria.” A backhanded compliment if there ever was one. This dismissive attitude pushed Vodou further into the shadows, labeled a relic unfit for modern society.

The Spotlight From Abroad: Mockery and Political Tool

Haiti, the first Black republic born from a slave revolt, intrigued and terrified the world. European and American newspapers gleefully mocked Haiti’s leaders and culture. The press painted Haiti as chaotic, exotic, even savage. Vodou became an easy symbol for those narratives.

Some in Europe and America saw Haiti’s struggles as evidence that Black people couldn’t govern themselves. Vodou, linking Haitians back to Africa, was portrayed as evidence of irrational barbarism. This narrative helped justify slavery’s continuation and colonial ambitions elsewhere.

Early Accounts: Moreau de Saint-Méry’s Cautionary Notes

In 1797, a French slave-owner named Moreau de Saint-Méry wrote a detailed account of Vodou ceremonies. He described its African origins and rituals with a mix of fascination and fear. According to him, Vodou dances had magnetic power, even compelling white spies to dance involuntarily. If that’s not eerie, what is?

Interestingly, Saint-Méry didn’t accuse Vodou followers of cannibalism or human sacrifices. Instead, his concerns lay with animal sacrifices and the scandalous sex orgies rumored to end ceremonies. Sensationalism, however, took on a life of its own in later tellings.

Vodou in the Public Eye: Faustin Soulouque’s Regime

By 1850, Vodou was visible enough to catch international headlines. Emperor Faustin Soulouque openly practiced Vodou ceremonies. A French newspaper, La Presse, reported a grand ritual including animal sacrifices, with French warships firing cannons in the background. Fancy imagery, right?

But the paper’s verdict was harsh: Haiti was backsliding into savagery. The emperor himself revived “religious ceremonies of the Congo and Guinea” that previous rulers tried to stamp out. The message was clear—Vodou was backward and a threat to civilization.

Mid-19th Century Views: Part-Religion, Part-Witchcraft

French writers of the time largely saw Vodou as a strange, hybrid club—a mix of religion, witchcraft, and social gatherings. They highlighted its bizarre ceremonies and rumored orgies. While considered barbaric, it wasn’t yet branded outright satanic. More “weird club” than “evil cult.”

The Bizoton Affair: When Horror Hardened Fear

Then came the event that cemented Vodou’s dark reputation in the popular imagination—a gruesome crime that shocked Haiti and the world.

In December 1863, siblings Jeanne and Congo Pellé, allegedly commanded by a Vodou god, kidnapped their niece Claircine. They held her captive for four days before strangling her, decapitating her, and then cannibalizing her in a macabre feast with other Vodou followers. The police stopped a second child from suffering the same fate.

The trial dominated Haitian newspapers and even made headlines in France. Eight people were executed, the crowd cheering. The massacre offered an excuse for voices calling for the destruction of Vodou itself.

Journalist A. Monfleury wrote in Le Moniteur Haïtien that eradicating Vodou was essential since the religion’s dark rituals bred such horrors. “A cult can only be destroyed by another cult,” he proclaimed, pushing for Christian supremacy as the antidote.

Anti-Vodou Campaigns and the Role of the Church

Following the Bizoton Affair, Haiti’s government took steps to suppress Vodou. President Geffrard signed a pact with the Vatican in 1860 to strengthen Catholicism’s hold and stamp out Vodou as a “devil cult.”

New French clergy arrived, particularly from Brittany, bringing strict anti-Vodou campaigns. These efforts stretched well into the 20th century—most notably the campaigns from 1939 to 1942, aiming to wipe away African religious practices deemed “barbaric.”

So, Why Did Vodou Get Such a Bad Rap?

- Colonial fear of rebellion and loss of control turned Vodou into a symbol of witchcraft and savagery.

- Haitian elites internalized European prejudices, dismissing Vodou as unfit for a modern nation.

- Foreign media mocked and exaggerated Vodou to delegitimize Haiti’s independence and fuel racist agendas.

- Dramatic events like the Bizoton Affair gave real horror stories that stuck in public imagination.

- Religious authorities and state power collaborated to suppress Vodou, branding it as evil to strengthen Christianity.

What’s the Real Vodou?

Vodou is not the evil, bloodthirsty cult that films and stories make it out to be. It is a complex spiritual system honoring ancestors, nature, and a pantheon of divine beings called lwa. It centers community, healing, and resilience.

The cruel irony? Many harmful stereotypes of Vodou come from a mix of fear, misunderstanding, and political manipulation rather than direct evidence.

Feeling Curious? Here’s a Tip for Real Insight

If interested, seek voices from practitioners themselves—scholars, Haitian communities, or documentaries offering respectful portrayals. You’ll find rich traditions far removed from Hollywood horror stories.

Questions to ponder:

- How do spiritual practices become stigmatized by power structures?

- What roles do the media and elites play in shaping myths around cultures?

- Can a religion survive—and even thrive—under suppression and misunderstanding?

Bottom Line

Vodou’s reputation as a sinister cult didn’t arise in a void. It grew out of colonialism, racism, political machinations, sensational journalism, and a few tragic crimes—not because Vodou itself is evil.

Understanding this history cuts through the fog of myths. Rather than fearing Vodou, we can appreciate it as a vibrant spiritual tradition with deep roots in Haitian identity.

Why did colonial authorities see Vodou as witchcraft?

Colonial powers viewed Vodou as a dangerous form of witchcraft. They feared its African roots and the power it held over local populations. This fear helped justify colonial control and repression.

How did Haitian elites contribute to Vodou’s negative image?

Many educated Haitian elites, influenced by European ideas, saw Vodou as backward and uncivilized. They minimized its importance or described it as wild entertainment mixed with harmful behaviors.

What role did foreign media play in shaping Vodou’s reputation?

European and American press mocked Haiti and linked Vodou to savagery. This portrayal supported racist ideas that Black people could not govern themselves, using Vodou as evidence.

How did the Bizoton affair affect public views on Vodou?

The Bizoton affair involved a human sacrifice and cannibalism linked to Vodou. The widely publicized trial intensified fears and calls to eliminate Vodou as a harmful cult.

Did early accounts of Vodou promote myths of evil practices?

Early descriptions focused more on sensational aspects like wild dances and animal sacrifice. They did not claim widespread cannibalism but emphasized mysterious and powerful rituals.