The custom of plucking flower petals while reciting “He loves me, he loves me not” likely originates from European folk traditions dating back to at least the early 18th century, though its precise beginnings remain unclear due to scarce documented evidence.

This form of love divination appears mostly in 18th-century French literature and art. The earliest known literary mention is from Lettres historiques et galantes (1718) by Mrs. du Noyer, where a shepherdess, Amarante, uses a flower to determine her lover’s feelings in a binary manner—either “he loves me” or “he loves me not.”

Earlier still, the 1739 fantasy text Les femmes militaires describes a similar custom. In it, women on a fictional utopian island pluck flower petals, but instead of the binary outcome, each petal indicates the degree of love: Il l’aime un petit brin, moult, chaudement, prou, point du tout (He loves her a little, a lot, hotly, sufficiently, not at all).

Artist Jean-Baptiste Greuze immortalized the custom in his 1759 painting La simplicité. The artwork depicts a young woman plucking petals from a daisy, implying the presence of the love-me-love-me-not game in popular culture at that time. Greuze’s companion piece shows a shepherd blowing dandelion seeds, seeking signs from nature, indicating a broader interest in pastoral themes and divination.

A pop historian, Anne Pouget, claims in Le Grand Livre des pourquoi (2013) that the game started in the Middle Ages on Ile aux Vaches (now part of Île Saint-Louis in Paris), a once rural area where lovers sought privacy. They called the ritual “plucking the daisy” (cueillir la marguerite). However, Pouget’s claim lacks cited sources, and the evidence for medieval origins is weak. Similar statements were made in texts from 1902-1905, but these too are not confirmed as factual.

The tradition’s exact starting point is challenging to establish since customs like this are often passed orally and only appear in the record when featured in art or literature—often many years after they become popular. Researchers note the potential influence of 18th-century pastoral literature and artwork in spreading these themes widely across Europe.

The dandelion variation highlighted by Greuze shows that different plants were used for love divination, sometimes with altered rules and extended outcomes, like predicting the length of life instead of romantic feelings. The daisy game remains the most popular and enduring form.

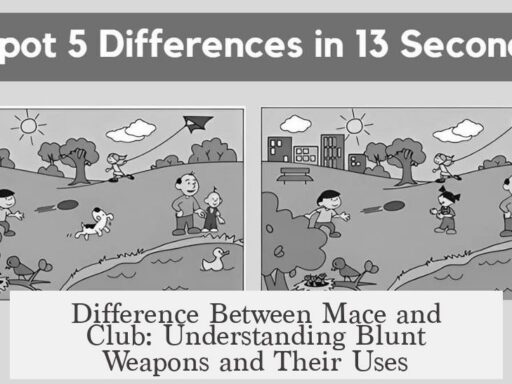

| Period | Evidence | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1718 | Lettres historiques et galantes (poem) | Binary love-me-love-me-not game by a shepherdess. |

| 1739 | Les femmes militaires | Multi-level love prediction by plucking petals. |

| 1759 | Painting La simplicité by Greuze | Visual depiction of a woman picking daisy petals. |

| Medieval (unconfirmed) | Claim by Anne Pouget (2013) | Rumored origin on Ile aux Vaches, no strong evidence. |

More detailed primary research could confirm if the theme existed in the 17th century or before, but current documented evidence points mostly to the 18th century as when the petal-plucking divination first entered common cultural records.

- The love-me-love-me-not game appears in 18th-century French literature and art.

- Anne Pouget’s medieval origin claim lacks strong evidence.

- Jean-Baptiste Greuze’s 1759 painting provides early visual proof.

- Different versions vary in complexity—from binary outcomes to multiple degrees of love.

- Pastoral themes in the 18th century helped popularize love divination by plant rituals.

The Curious Tale Behind “He Loves Me, He Loves Me Not”: The Origin of Using Flower Petals to Divine Love

“He loves me, he loves me not” is a charming game of love and chance played by plucking flower petals to discern a lover’s feelings. But where did this quirky custom come from? The short answer: it’s complicated, partly shrouded in history and myth, and its true origin is tricky to pin down.

This familiar ritual isn’t just random whimsy. It carries centuries-old echoes of human longing and secret whispers of love lost or hoped for. Yet, like many folk traditions, it creeps quietly into our history, often unrecorded until an artist or writer decides to capture it.

Why Tracing This Tradition Feels Like Picking Petals Blindfolded

Customs like this evade direct historical records because they are popular, passed down by word of mouth, not official chronicles. They only appear when a painter or writer immortalizes them. So, if you want proof, you need to read between the lines of old art or literature.

Still, the game’s existence pops up repeatedly over time, suggesting it’s been around longer than we realize.

Medieval Pastures and Lovers’ Secrets: Anne Pouget’s Theory

Pop historian Anne Pouget offers a colorful origin story. According to her 2013 book Le Grand Livre des pourquoi, this petal-plucking game began in medieval Paris on a little island called Ile aux Vaches (Cows’ Island).

Back then, it was a quiet pasture where lovers escaped for privacy. Pouget says these lovers “pluck the daisy” – or cueillir la marguerite – as a romantic pastime to divine affection.

Sounds idyllic, right? Except Pouget doesn’t cite any sources, which makes serious historians raise an eyebrow. This tale is fun but leans more toward legend than solid fact. Even a turn-of-the-century French book mentions it without confirming it as truth.

Art Speaks Louder: Jean-Baptiste Greuze’s 1759 Painting

Take a stroll to 18th-century France, and you find a more concrete hint. In 1759, artist Jean-Baptiste Greuze painted La simplicité, showing a young woman picking daisy petals. This isn’t a random detail. It depicts the very act of love’s uncertainty captured visually long before Goethe penned his romantic tales.

Greuze’s companion piece features a shepherd holding a dandelion, blowing the seeds—another version of seeking fate’s answer but with nature’s twist. If all seeds fly away, love’s winds are fair; if some linger, trouble may brew in the heart.

A Playground for Love: “Les femmes militaires” and a French Twist

Step back to 1739. A fantasy book titled Les femmes militaires paints a utopian island where women share power with men—and play variations of the petal game.

Instead of the simple “he loves me, he loves me not,” the French version in this story measured love’s intensity, not just a binary outcome. As one character picks petals, she recites phrases like:

“Il l’aime un petit brin, moult, chaudement, prou, point du tout.”

He loves her a little, a lot, hotly, sufficiently, not at all.

This multi-layered game adds nuance to the emotional lottery, reflecting how love itself isn’t always just yes or no.

The Earliest Recorded Poem: Love and Petals from 1718

If you crave historical proof, one of the earliest mentions comes from a 1718 poem in Lettres historiques et galantes by Mrs. du Noyer. In Gloire et Amour, a shepherdess named Amarante picks flower petals to see if her love, Thirsis, feels the same.

It’s a simple game, but the poem poignantly advises to trust the heart more than petals, hinting at an age-old human struggle between fate and feeling.

Origin: Probably Older Than You Thought, But Research Is Ongoing

It’s quite likely that flower petal divination games existed as early as the 17th century, but we need more primary sources to confirm exact origins. What we do know is that the ritual spread widely in Europe and warmed many hearts, becoming part of the romantic folklore we cherish today.

Art and Literature: The Romeo and Juliet of Pastoral Fun

The 18th century pastoral romance genre featuring shepherds and shepherdesses probably boosted the popularity of these flower games. Whether it’s Greuze’s paintings or ballads sung by lovers, these stories made the game fashionable and enduring.

Interestingly, Greuze’s dandelion game even had a spooky twist—some versions predicted years before one’s death. Talk about high stakes for a flower game!

Why Do We Still Pluck Petals Today?

The game survives because it’s simple, poetic, and taps into a deep human desire: to know if we are loved. It’s a playful act that offers hope and suspense with every petal torn away.

Whether it’s a daisy, a dandelion, or a metaphorical question posed silently to the wind, this ritual reminds us that love’s certainty is elusive, and sometimes, it’s about the fun in the guessing.

Some Tips for Playing “He Loves Me, He Loves Me Not”—With Flair

- Choose your flower wisely. Daisies are classic, but try aster or chrysanthemum for a quirky twist.

- Make it poetic. Assign personalized meanings to petals instead of just two options. For example, “He loves me a little,” “He’s confused,” or “He’s totally smitten.”

- Pair the game with a handwritten note or a whispered wish to add romance.

- Remember: it’s a game, not a prophecy. Use it to spark smiles, not stress.

In Conclusion

The origin of the “He loves me, he loves me not” flower petal game is a delightful mystery. It likely blossomed sometime between the 17th and 18th centuries, nurtured by pastoral literature, romantic hopes, and the creative whims of artists like Jean-Baptiste Greuze.

While Anne Pouget’s medieval pasture story adds charm, it’s best taken with a grain of skepticism. Instead, we lean on early poems, paintings, and 18th-century literature as stronger proof of its roots.

So next time you pluck a daisy petal, remember: you’re partaking in a centuries-old ritual that blends art, love, chance, and a little bit of whimsy. Whether your petal says “he loves me” or not, the true magic lies in daring to hope and play. And hey, doesn’t love deserve a playful game now and then?