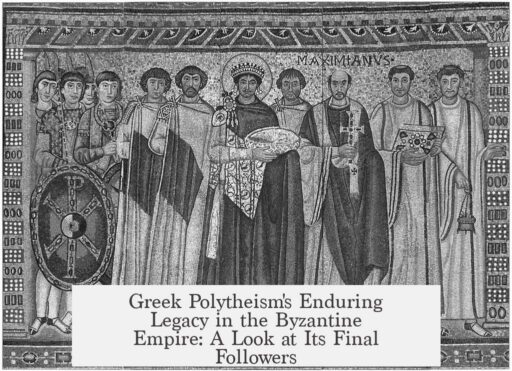

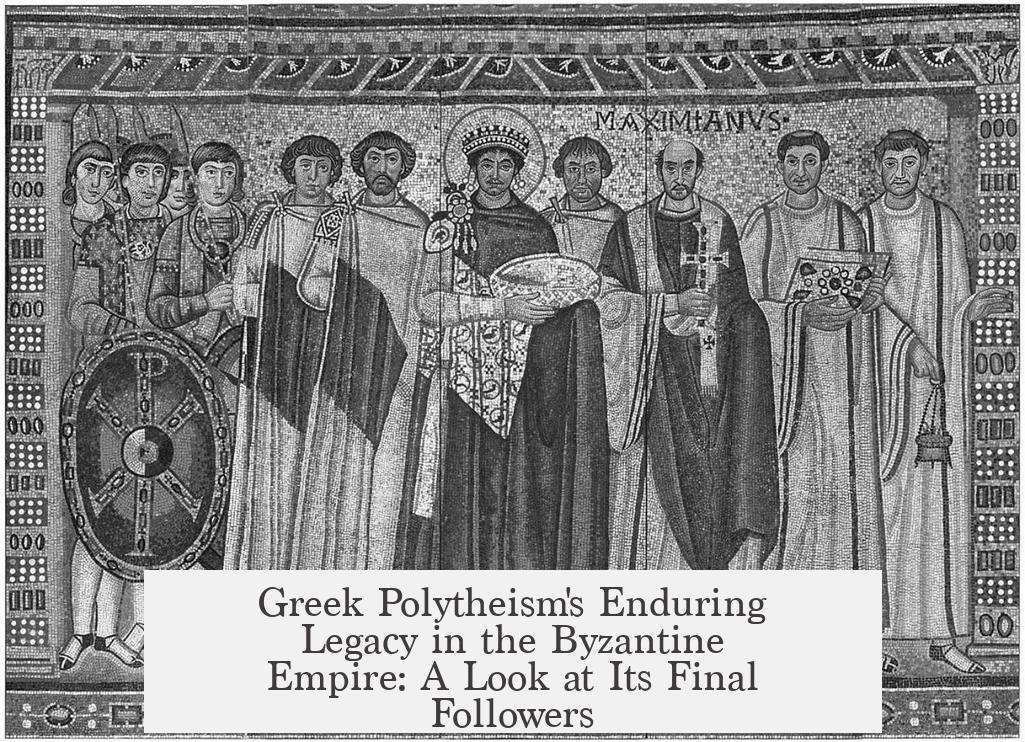

Greek polytheism by its last few generations in the Byzantine Empire, particularly if existing up to the 11th century, likely appeared as a greatly diminished and transformed religious practice. Evidence suggests that the well-known pagan community of Mani, often cited as a late stronghold of Hellenistic polytheism, probably ceased pagan worship by the 9th century, around the reign of Basil the Makedonian.

The precise characteristics of Greek polytheism near its end remain unclear due to a significant lack of contemporary sources. There are no surviving firsthand accounts from the practitioners themselves. This gap leaves modern scholars without direct knowledge of their beliefs, rituals, or sacred spaces.

External descriptions from Christian or Muslim neighbors are also extremely limited. Narratives about the Maniots or similar groups’ religious life rarely provide detailed insights into their rituals or theological outlook. Most available information comes from brief historical records and a few inscriptions indicating that conversion to Christianity occurred by the 9th century.

Consequently, the late-stage practices of Greek polytheists—should they have existed into the 10th or 11th centuries—were probably syncretic or altered from classical forms. Their worship spaces, typically temples or outdoor sanctuaries in earlier eras, might have been abandoned, repurposed, or reduced to informal shrines. Interactions with Christian neighbors likely ranged from peaceful coexistence to pressure for conversion.

The cultural and religious environment in the Byzantine period increasingly favored Christianity, making open pagan worship difficult and rare. Thus, any remaining polytheism would have survived in isolated, rural, or mountainous areas with minimal contact.

| Aspect | Likely Situation by 10th-11th Century |

|---|---|

| Community Size | Very small, possibly individual families or isolated groups |

| Practices | Modified or heavily syncretized rituals; loss of formal temples |

| Worship Spaces | Informal shrines or ancestral sites; few or no public temples |

| Interactions with Christians | Likely cautious coexistence or pressure to convert |

| Sources | Scarce inscriptions; no practitioner records; minimal external descriptions |

The absence of detailed records means that modern reconstructions rely on limited archaeological data and brief historical references. Greek polytheism at this late stage symbolized a fading tradition, overshadowed by the dominant Christian Byzantine culture.

- No direct accounts from late practitioners exist.

- External descriptions of remaining polytheists are sparse and vague.

- The last pagan groups, such as the Maniots, likely converted by the 9th century.

- Rituals and worship spaces had probably changed significantly or disappeared.

- Late Greek polytheism likely survived only in small, isolated areas.

Greek Polytheism’s Last Stand in the Byzantine Empire: What Did It Look Like?

Imagine this: Greek polytheism, once the vibrant soul of Hellenistic culture, still flickering in shadowy corners of the Byzantine Empire well into the 11th century. What would this ancient religion have looked like then—its twilight years, just before the final curtain? The short answer: it was a deeply diminished, widely misunderstood remnant more rooted in memory than practice.

But hold on. Before we paint a romantic picture of secret temples and clandestine festivals, let’s address some historical reality checks.

The Curious Case of the Maniots and the Timeline of Decline

The Mani Peninsula in southern Greece is often pointed to as perhaps the last refuge of classical polytheism. Contemporary literary sources suggest the Maniots clung to remnants of Greek paganism until about the 9th century. The idea they survived till the 11th century, as some hope, faces significant doubt. According to historical consensus, their conversion to Christianity likely occurred during the reign of Basil I (867–886 AD).

So, by the 11th century, classical Greek polytheism had most probably faded into history—officially. However, let’s not dismiss the cultural “aftershocks.”

Lack of Primary Sources: The Silent Void of Polytheistic Voices

A major hurdle in understanding the late state of Greek polytheism is the complete absence of writings from its own followers. No diaries, no treatises, no hymns penned by adherents exist from this period. This silence means historians rely almost exclusively on external accounts or, better said, the lack thereof.

Even outsiders, whether Christian or Muslim chroniclers, provide sparse and vague details. There’s no rich description of Maniot rituals or theology—only hints here and there. From a historian’s perspective, it’s like trying to reconstruct a symphony from a few scattered notes.

What Might Have Remained of Greek Polytheism—Folklore, Rituals, or Just Memories?

With such scant evidence, what can we reasonably imagine about the last manifestations of this religious tradition? It’s tempting to assume that by the 11th century, polytheism had shifted far from the classical grandeur of Olympus and temples. Instead, it likely became a syncretic, localized practice with fading temple worship, limited priesthood, and a patchwork of surviving myths.

Some theories suggest worship spaces would no longer have been grand or public but rather hidden shrines in remote areas, perhaps akin to household altars or small groves. Perhaps rituals had softened into folk customs, blurred with Christian festivities.

Consider this: religious belief rarely dies suddenly. It morphs and mingles with the dominant religion—in this case, Eastern Orthodox Christianity. So possibly, certain festivals or mythic tales survived, repurposed into Christian narratives or quietly practiced alongside new beliefs.

A Community on the Edge: Relationship With Their Christian Neighbors

How did the last polytheists live among their Christianized neighbors? This is murky. Without detailed descriptions, we rely on educated guesses. They might have been either fiercely protective of their traditions or simply resigned to survival in privacy.

Know this—religions don’t like disappearing alone; they mingle, sometimes fading into the background, or stubbornly persisting on the fringes. The Maniots and similar groups might have maintained a delicate balance, outwardly conforming but privately maintaining older rites, or possibly weaving new traditions into old myths.

But Why Does It Matter? The Legacy and Lessons

Understanding late Byzantine Greek polytheism isn’t just an academic puzzle; it’s a window into cultural resilience and transformation. Talking about these last generations lets us appreciate how faith adapts—or struggles to adapt—in changing environments.

Moreover, it reminds us history isn’t just about the winners or mainstream stories. Marginal groups hold keys to richer, more nuanced views of the past. Archaeological finds like inscriptions, no matter how few, offer clues that even in decline, a shadow of Hellenistic culture persisted.

Final Thoughts: The Unsatisfying Truth and the Mystery That Remains

To be honest, historians would love to say more about how Greek polytheism looked in the 11th century. But the reality is frustratingly thin. What we know is based on limited scraps—scattered inscriptions, a few brief records, and absence of evidence elsewhere.

So, Greek polytheism by its final act was most likely a faint echo of itself—a culture barely hanging on in isolated spots, mostly forgotten amid a sea of Christian dominance. Its last followers lived in obscurity, their rituals simplified or secretive, their beliefs probably altered by centuries of contact and pressure from the new religious order.

Do you find it intriguing how religions evolve under pressure? Could similar silent transitions be happening today with other belief systems? History suggests faith is rarely extinguished overnight. Instead, it transforms, hiding in plain sight, adapting in ways we might only discover through careful study and sensitive imagination.

In the end, Greek polytheism’s last generations represent more a story of quiet survival and cultural memory than thriving worship—a timeless reminder that even ancient gods face the slow quiet fade of history.

What evidence exists for Greek polytheism surviving into the 11th century?

There is little direct evidence for Greek polytheism lasting until the 11th century. Most sources suggest that polytheistic communities, such as the Maniots, had converted by the 9th century. Only faint traces like inscriptions remain.

How much is known about the beliefs of the last Greek polytheists?

Very little is known. There are no firsthand accounts from practitioners. External descriptions from Christians or Muslims are scarce and lack detail. This leaves their actual beliefs largely unknown.

What do we know about their worship practices and temples?

Details on worship spaces or rituals are missing. It is unclear how much their practices had changed or adapted by this late period. The nature of their religious life remains uncertain.

Did late Greek polytheists coexist peacefully with Christians?

The relationship between the remaining polytheists and their Christian neighbors is not well documented. We do not have clear evidence about interaction or conflict during this time.

Why is it hard to study late Byzantine Greek polytheism?

There is a lack of primary sources from practitioners and minimal detailed external reports. Historical records are sparse, making it difficult to reconstruct the practices of these last polytheists.