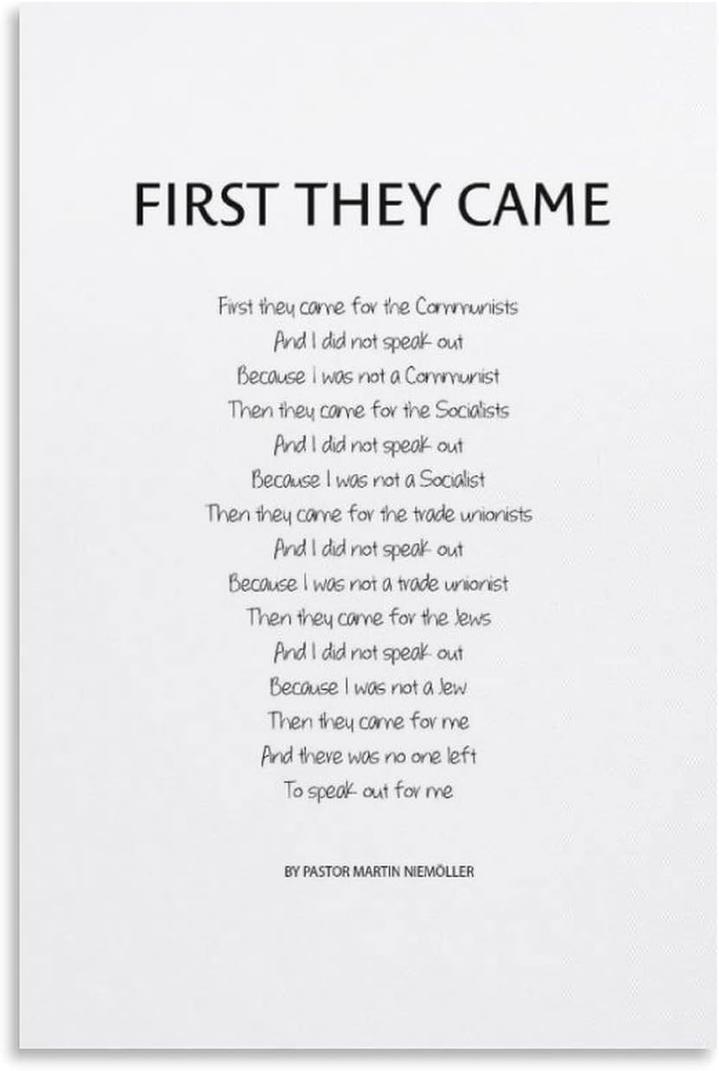

“First they came…” is a famous poem by Martin Niemöller reflecting the dangers of remaining silent in the face of injustice. Niemöller’s verses trace the progressive persecution under Nazi rule, illustrating how indifference to others’ suffering ultimately leads to a loss of protection for all.

The original poem goes:

First they came for the Communists And I did not speak out Because I was not a Communist Then they came for the Socialists And I did not speak out Because I was not a Socialist Then they came for the trade unionists And I did not speak out Because I was not a trade unionist Then they came for the Jews And I did not speak out Because I was not a Jew Then they came for me And there was no one left To speak out for me

This poem traces groups targeted by the Nazis and highlights the personal and societal consequences of silence. Each stanza shows how ignoring injustice against one group allows further oppression, eventually threatening everyone.

Several modifications to the poem exist. During the 1950s Cold War, the Holocaust Museum edited it, removing the initial line about communists. This reflects political tensions of that era and impacts the poem’s framing. Also, Niemöller initially did not include Jews in his version, as he originally spoke only about communists, socialists, and trade unionists.

Notably, Niemöller’s own background is complex. He initially supported Hitler and opposed the Weimar Republic. He himself aided the Nazi rise to power. His opposition emerged only after Nazis forced Christian churches to expel members of Jewish descent and started persecuting groups closely related to his faith. This context tempers simplistic interpretations of the poem as solely a confession of personal failure.

Moreover, Niemöller did speak out against the Nazis later, which complicates the idea that he entirely remained silent. His poem functions more as a moral warning than a literal confession.

The poem’s impact and interpretation have evolved over time. Its power lies in exposing passive complicity in the face of oppression. For Jewish communities in Eastern Europe under Nazi rule, it resonates deeply. Many people witnessed atrocities but did not intervene, either due to fear, prejudice, or calculated indifference. Allied liberators sometimes forced local residents to confront their complicity in nearby concentration camps.

Critics argue the poem oversimplifies the moral struggle faced by individuals. They emphasize that people should act not out of self-preservation but from a recognition that persecution is inherently wrong. The poem’s framing risks portraying resistance as merely pragmatic rather than principled.

Further nuance involves distinguishing personal failings from institutional power. Fascist regimes wield immense resources to coerce or suppress populations. Blaming individuals alone ignores how authoritarian governments manipulate societies—through propaganda, intimidation, and legal structures—to silence opposition. The relationship between citizens and regimes is complex and cannot be reduced to simple notions of “good” versus “bad” people.

Additionally, many Germans and others outside persecuted groups experienced safety or privilege during Nazi rule, which influenced responses. For many, survival appeared to depend on maintaining distance from the targeted. This makes the poem’s call to act a challenge, highlighting the tension between individual risk and collective responsibility.

The poem is sometimes misattributed, such as in Latin America where it is wrongly linked to a figure named Alberto Brecht. This underlines the importance of historical accuracy in preserving the meaning and legacy of works addressing human rights and moral courage.

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Author | Martin Niemöller, German Lutheran pastor |

| Original Target Groups | Communists, Socialists, Trade unionists, Jews, Niemöller himself |

| Initial Political Stance | Early supporter of Hitler, later opponent |

| Main Theme | Consequences of not speaking out against oppression |

| Common Misattributions | Altered versions in Cold War period; attributed to Alberto Brecht in Latin America |

| Interpretative Challenges | Balancing individual choice with institutional coercion; moral responsibility beyond self-interest |

- The poem warns that silence during persecution harms society later.

- Niemöller’s complex history includes initial Nazi support and later resistance.

- Versions of the poem differ and omission of groups changes its scope.

- Interpretation involves understanding fear, complicity, and power structures.

- The poem highlights timeless issues of moral duty and human rights.

The Real Story Behind “First They Came…”

First they came for the Communists, And I did not speak out Because I was not a Communist… These haunting words strike a chord in many hearts. But is the poem as simple—or as truthful—as it seems?

This post peels back layers around the famous “First they came…” poem, revealing surprising twists you probably haven’t heard. Let’s dive into the poem’s origin, its author Martin Niemöller’s complex past, and the deeper meaning behind this cautionary tale.

The Poem: What You Thought You Knew

The classic poem lists groups persecuted by the Nazis—communists, socialists, trade unionists, Jews—explaining why people stayed silent. Its crescendo warns that silence ultimately leaves no one to defend you. The version most know goes like this:

First they came for the Communists And I did not speak out Because I was not a Communist Then they came for the Socialists And I did not speak out Because I was not a Socialist Then they came for the trade unionists And I did not speak out Because I was not a trade unionist Then they came for the Jews And I did not speak out Because I was not a Jew Then they came for me And there was no one left To speak out for me

This poem carries heavy weight, no doubt. But few know the truth behind its words, how they evolved, and what the author really wanted to convey.

The Original Poem and Its Changes

First, the version above is actually a modified one, shaped by political winds of the Cold War. The original included a line about communists but sometimes the poem’s first line was removed. Why? Because during the 1950s, when the Holocaust Museum edited the poem, the Soviet Union was the new enemy, making it awkward to emphasize Nazi persecution of communists.

Fun fact: In Latin America, people often mistakenly credit the poem to Alberto Brecht. Nope, that was Hermann Albert Niemöller.

Another surprising point is that Niemöller originally didn’t include Jews in his poem. At first, he only mentioned communists, socialists, and trade unionists. He added the line about Jews only after World War II. Why? Because Niemöller himself was a Nazi supporter before his falling out with the regime.

The earliest versions were in German, like this:

Als die Nazis die Kommunisten holten, habe ich geschwiegen; ich war ja kein Kommunist…

The omission of Jews at first—and later sometimes omitting communists—says a lot about how this poem was reinterpreted and repurposed over time. It’s less about a constant, fixed truth and more about shifting politics and memory.

Martin Niemöller: Not Just a Victim

Who was Niemöller? The man behind this emblematic poem had a complicated past. He wasn’t a passive bystander from the start. In fact, Niemöller initially supported Hitler and the Nazis.

He opposed the Weimar Republic and welcomed the Nazi rise to power, seeing it as a way to restore Germany’s greatness. He went beyond silence; he aided the Nazis in their early years.

His transformation came later. Niemöller fiercely opposed the Nazi regime only after they forced the Church to expel Christians of Jewish descent. That was when Niemöller realized the Nazis would not stop with political enemies.

Moreover, Niemöller did speak out. So, his famous statement of silence is more a moral confession than a literal historical record.

Why Does This Matter?

This complexity challenges the neat, simplistic moral we often take from the poem. It’s not just about “fear keeps you quiet” or “speak up or suffer later.” There’s a lot of shades of gray here.

Do we blame people for not standing up to overwhelming power? Or do we recognize that institutional forces use coercion and propaganda to silence dissent? The poem’s message is powerful but fixing it solely on individual guilt misses the bigger picture.

The Poem’s Impact and Its Modern Resonance

Certainly, its relevance surged after WWII and remains potent today. I recently visited the Holocaust Museum in Washington, DC, where this poem echoes loudly for many Jews from Eastern Europe. People often witnessed Nazi crimes or heard rumors of atrocities against Jews but chose not to act because it “wasn’t their problem” or due to ingrained anti-Semitism.

Many townspeople near concentration camps stood silent or complicit, and when Allies liberated these areas, they forced locals to confront the horrors. Some reacted with disbelief or guilt; others, denial.

But here’s a critical nuance: many Germans who were neither Jews, Roma, homosexuals, Jehovah’s Witnesses, nor political minorities remained safely untouched by Nazi terror, sometimes even benefiting from it.

So, not everyone had the same level of risk or moral clarity in their choices. This reality complicates the blanket moral lessons often drawn.

What Can We Learn Today?

The poem urges vigilance but does so in a way that sometimes distorts the moral struggle. The right motivation to act isn’t “because they will come for you next,” but because persecution itself is wrong.

Recognizing this can help us resist the seduction of selfish silence in face of injustice. It reminds us to speak out not for fear of personal loss alone but to protect human dignity.

Yet, we must balance that with empathy for those caught in systems they can’t easily oppose. There’s no simple “good versus bad” label for individuals under oppressive regimes. Institutions wield terrifying power, and too often manipulate populations to their ends.

Bringing Clarity to a Famous Tale

The “First they came…” poem endures for good reason. It captures the danger of apathy and the cost of silence. But polishing it up with historical truths gives it sharper edges.

- The poem’s original form changed over decades, reflecting political climates and memory politics.

- Its author, Niemöller, began as a Nazi supporter, complicating the narrative of passive innocence.

- People’s silence during Nazi Germany stemmed from fear, self-preservation, and sometimes shared prejudice—not only moral failing.

- Persecution’s impact wasn’t equal; safety sometimes bred complacency.

- The ultimate lesson is better framed as a call to action on grounds of justice and human rights, not just personal fear.

So next time you hear “First they came…” remember: history often laughs at neat stories. Instead, it asks us to wrestle with uncomfortable truths and sharpen our understanding of human behavior.

Are you ready to speak out when it matters, or just when it might matter to you? The poem invites us to ask this question honestly.

Tips for Applying These Lessons Today

- Educate Yourself: Don’t take popular narratives at face value. Dig into history from multiple perspectives.

- Recognize Systemic Forces: Understand how institutions manipulate public opinion and squash dissent.

- Act on Principle: Stand against injustice because it’s wrong, not just when it hits close to home.

- Empathize with the Caught: Not everyone can resist oppression easily—judging individuals harshly oversimplifies reality.

- Speak Up Early: Silence can be complicity. When you witness harm, say something immediately.

In our complex world, Niemöller’s poem remains a vital warning. But it becomes even stronger when we tell the whole story. Not just about those who stayed silent, but those who struggled, supported, or resisted.

First they came… Let’s make sure we come next—for justice, truth, and each other.

What is the original version of the poem “First they came…”?

The original poem lists political and social groups targeted by the Nazis: Communists, Socialists, trade unionists, and Jews. It ends with “Then they came for me, and there was no one left to speak out for me.”

How did Martin Niemöller’s background affect the poem?

Niemöller initially supported Hitler and the Nazis. He only opposed them after they forced the church to expel Christians with Jewish ancestry. His later opposition influenced the poem’s message.

Why was the poem altered by the Holocaust Museum in the 1950s?

The museum changed the poem during the Cold War to remove the line about Communists. This was to avoid conflict with the Soviet Union and to adapt the poem’s political impact.

Is the poem a confession of Niemöller’s silence during Nazi persecution?

Not exactly. Niemöller did speak out eventually. The poem represents a warning about indifference, though it simplifies his and others’ actual responses to fascism.

What does the poem say about individual responsibility during persecution?

The poem highlights the risks of not opposing oppression early. It warns that ignoring injustice against others can leave no defenders when one’s own rights are threatened.