The Roman Empire did not truly fall in 476 AD; rather, its western half fragmented while the Eastern Roman Empire, often called the Byzantine Empire, persisted until 1453. Both dates hold importance, but 1453 marks the final and more definitive end of the Roman imperial structure in history.

The year 476 AD is widely cited as the fall of the Roman Empire because Romulus Augustulus, the last emperor in the West, was deposed by Odoacer. Yet, this event oversimplifies the empire’s complex decline. Romulus Augustulus was a minor usurper with a brief, contested claim. His removal did not end Roman governance or culture immediately. Odoacer, a Roman general of barbarian origin, simply replaced one power figure with another without abolishing Roman institutions.

Moreover, by 476, the western empire had already lost most of its territories outside Italy. Its disintegration was gradual, stretching across decades rather than a single decisive moment. Marcellinus Comes, a sixth-century chronicler, first framed 476 as the empire’s “end.” Before this, contemporaries saw it as one of many regime changes, not a collapse. Roman identities and customs continued in western regions despite diminished political unity.

Even after 476, the imperial line endured through Julius Nepos, a legitimate emperor recognized by the East. Nepos ruled Dalmatia until 480 AD, challenging the idea that Roman leadership ceased in 476. Constantinople acknowledged Odoacer’s rule over Italy as a deputy governance rather than outright rejection of imperial authority. Odoacer and subsequent rulers like Theodoric the Great upheld Roman political methods and titles, signaling continuity rather than rupture.

The Ostrogothic Kingdom in Italy under Theodoric (r. 493–526) offers a prime example. Though a “barbarian” regime, it maintained Roman administration, law, and culture, blending old imperial traditions with new leadership. Simultaneously, Frankish rulers like Clovis took on Roman titles. Coinage minted in their names initially bore the eastern emperor’s mark but later displayed independent rulership, indicating progressive separation but rooted continuity.

In the East, the Roman Empire thrived long after 476. The Byzantine Empire remained a powerful, wealthy entity with profound cultural influence on Europe and the Near East through the Middle Ages. Its capital, Constantinople, stood as a bastion of Roman governance and Orthodox Christianity until its fall to the Ottoman Turks in 1453.

Some historians argue that the “fall” of Rome is more a transformation than a collapse. They propose alternative dates: 235 AD, marking the beginning of imperial crises; 284 AD when Diocletian implemented the tetrarchy; or 629 AD when Emperor Heraclius adopted the Greek title *basileus*, signaling a cultural and political shift from Latin to Greek identity. The rise of the Byzantine Empire reflects this evolution rather than a simple fall.

Other key moments, such as the 1204 sack of Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade or the 1461 fall of the last Byzantine army, signify critical blows to Roman imperial identity. The final fall of Constantinople in 1453 symbolizes the definitive end of the Roman Empire as a political entity. Unlike 476, it signaled the loss of the eastern government, traditions, and imperial continuity.

Determining when Rome truly fell depends on how one defines “Roman Empire.” Possible defining attributes include:

- The city of Rome itself

- Roman political institutions and legal systems

- Roman cultural identity and language

- The imperial succession and legitimate emperor

- The role of Christianity within the empire

The Western Roman Empire ceased effective political unity in 476 but retained much Roman tradition. The Eastern Roman Empire maintained continuous governance, culture, and a clear imperial lineage until 1453. Thus, the question is not only about dates but about what defines the essence of Rome.

In sum, 476 marks the fall of Roman rule in Western Europe but not the empire’s entirety or legacy. The Eastern Roman Empire carried forth the Roman imperial tradition for centuries. The conquest of Constantinople in 1453 represents the final disappearance of the Roman Empire’s institutional and cultural continuity.

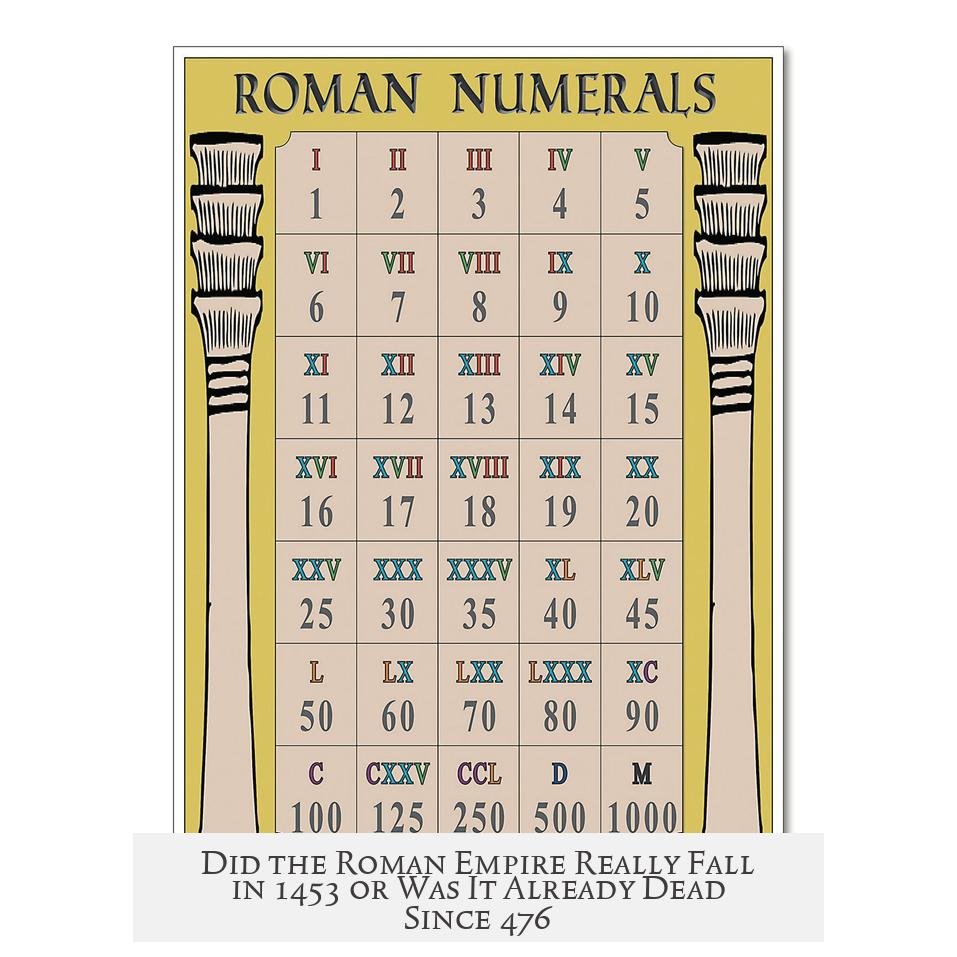

| Date | Event | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| 476 AD | Deposition of Romulus Augustulus | End of Western Roman imperial rule, symbolic but gradual decline |

| 480 AD | Death of Julius Nepos | Last legitimate Western emperor, continuing imperial line post-476 |

| 1453 AD | Fall of Constantinople | Final collapse of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire |

- 476 AD marked the end of Western Roman political unity, but Roman culture persisted.

- Eastern Roman Empire survived and thrived for nearly 1,000 years post-476.

- 1453 marks the conclusive fall of Roman imperial governance and tradition.

- Roman identity and institutions transformed progressively, not through sudden collapse.

- Defining Rome’s fall depends on criteria such as political power, culture, and institutional continuity.

Did the Roman Empire Really Fall in 1453 or Was It Already Dead Since 476?

The short answer is: The Roman Empire did not really fall in 476 AD; it lingered for nearly a thousand more years, finally coming to an end in 1453 with the fall of Constantinople. So why is 476 so famous? And why does 1453 feel like such a big deal? Let’s unpack this Roman saga, no sandals required.

First, let’s deal with the 476 AD claim. It’s the classic “This is when Rome fell!” line taught in schools and reenacted in countless movies. But in reality, 476 isn’t quite the Rome-ending mic drop it’s made out to be.

Romulus Augustulus, the so-called last Western Roman Emperor, was less of a grand ruler and more of a figurehead puppet. His reign lasted a couple of years and was largely insignificant politically. Odoacer, a Roman general (not some barbarian horde leader storming in), simply replaced one guy with another because he didn’t like the boss. This kind of thing happened often back then. So, 476 was more of a power shuffle in Italy than the curtains closing on the whole empire.

The Empire Was Already Half-Gone Before 476

By the mid-5th century, the western half of the empire had already lost most of its territories outside Italy. Regions like Gaul, Spain, and North Africa had fallen away to various kingdoms and groups. So 476 is not a sharp cut-off but more of the middle of a slow fade-out. This is why historians call the collapse a gradual process rather than an instant fall.

Also, the story around 476 was popularized by a chronicler, Marcellinus Comes, around 518. He framed it as the “end” for simplicity, but for many contemporaries, it was just one example of a regime change like many others in that turbulent era.

The reality? Roman culture and identity kept marching on in the West for centuries, even after 476.

But Wait! The Roman Empire Didn’t Exactly End in the West, Did It?

Enter Julius Nepos, a more legitimate emperor still kicking it—sort of—in Dalmatia, a region of the Balkans. Nepos was backed by the Eastern Roman Empire (the one based in Constantinople). His death in 480 is another date some historians throw into the “end of the Western Roman Empire” conversation. So if you want to pick a late date for the West, 480 makes as much sense as 476.

Odoacer and successors ruled Italy nominally under Eastern Emperor authority. The ruling “barbarians” didn’t really want to rock the boat. Theodoric the Great of the Ostrogoths even styled himself as a Roman emperor, preserving Roman political structures and culture rather than dismantling them.

Coinage reveals more clues. Early 6th-century “barbarian” kingdoms minted coins naming the Eastern Emperor to show allegiance. But over time, they started stamping their own names. This gradual change reflected that these rulers were asserting independence, especially after Justinian’s Byzantine reconquest of Italy in the mid-6th century. Even so, they played in Rome’s court, not rewriting the whole script.

What’s the Deal with the Eastern Roman Empire?

While the Western Empire stumbled, the Eastern Roman Empire, often called the Byzantine Empire by modern historians, flourished for many more centuries. For much of medieval Europe, it was a vibrant, wealthy power with thriving cities, culture, and military strength.

The East considered itself the true continuation of Rome. They called their emperor Caesar or Augustus just like old Rome. Their capital, Constantinople, was often known as “New Rome.”

Scholars mostly agree that the *real* end of the Roman Empire comes with the fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans in 1453. This marked the final shutdown of the Roman imperial lineage and government.

So by that logic, the “fall” took place nearly a millennium after 476.

But Wait, History Might Be Even Messier Than That

What even counts as the Roman Empire? Defining it isn’t easy. Is it:

- The city of Rome itself?

- Roman culture and legal traditions?

- The political institutions established over centuries?

- The Christian religion after Constantine?

- The continuous line of emperors?

Historians consider all these factors, and none gives a neat answer. Some even argue that the empire started changing so much as early as 235 AD with Emperor Alexander Severus’ death, or during Diocletian’s reforms in 284 when the tetrarchy reshaped governance.

Others point to 629 AD when Emperor Heraclius adopted the title basileus and shifted Roman identity from Latin to Greek. That was another major transformation rather than a “fall.”

Even the sack of Constantinople by Venetians in 1204 or the demise of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806 confuses the picture. The legacy of Rome twists through all these events, adapting constantly.

So Which Event Was More Important: 476 or 1453?

476 is iconic because it marks the end of Roman imperial power in Western Europe, a poignant symbol for the Middle Ages beginning. But it was a local collapse in Italy with many lingering Roman connections.

1453 is important because it closed a chapter on a continuous Roman state that lasted over 2,000 years through different forms.

That said, both dates serve different roles:

- 476 AD signals the fragmentation of the West into smaller kingdoms and the start of the medieval European world.

- 1453 AD signifies the true political end of the Roman imperial system established in antiquity.

Both shaped history deeply, but 1453 arguably holds more weight in defining the *end* of the Roman story, while 476 is more a milestone in its transformation.

Practical Takeaway: Why Care About These Dates?

Understanding the nuance behind these dates helps avoid oversimplifications like “Rome Fell and Europe Fell into the Dark Ages.” History is rarely snap-and-snap moments. It’s a slow-motion epic, with legacies, culture, and power lingering and evolving.

If you take anything away, it’s that Rome’s “fall” wasn’t a fall at all—it’s a transformation tapestry that stretched centuries. So the next time someone insists Rome fell in 476, you can smile and say, “Actually, the empire lived on—for centuries—just in a new dress.”

And besides, if you look at history as a long game of musical chairs with generals, emperors, cultures, and cities switching places, the Roman Empire is perhaps the champion who never quite left the dance floor.