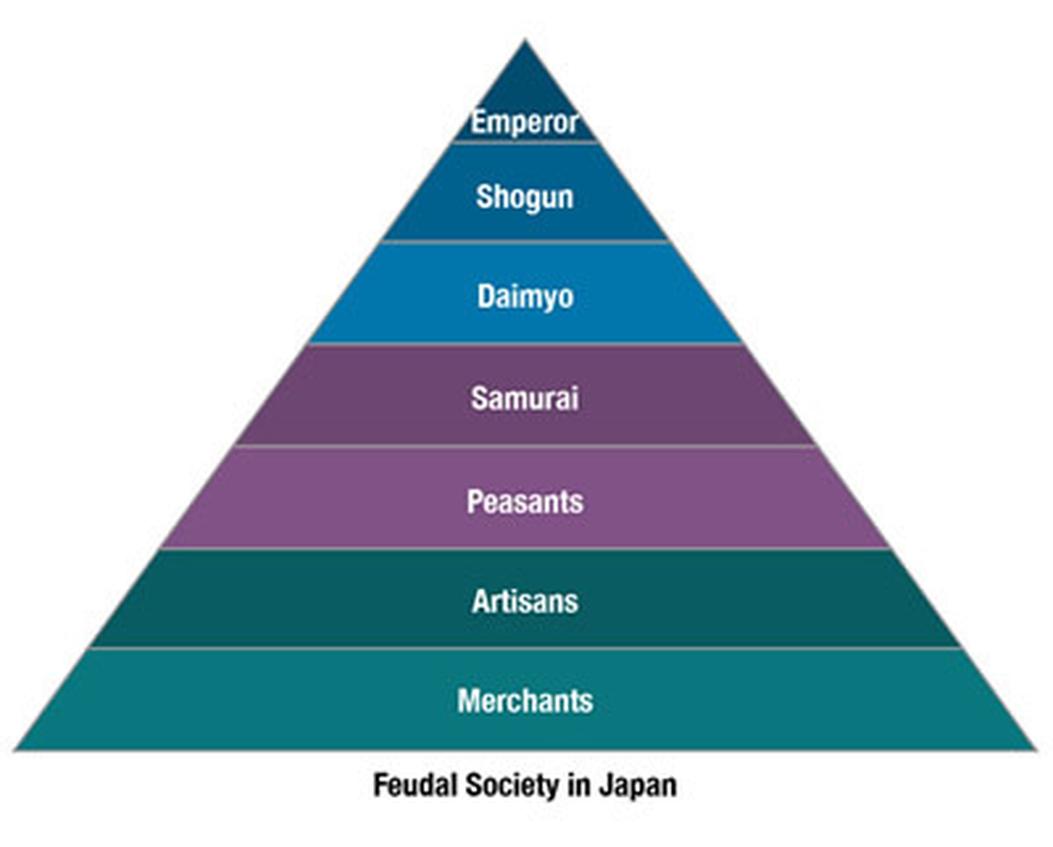

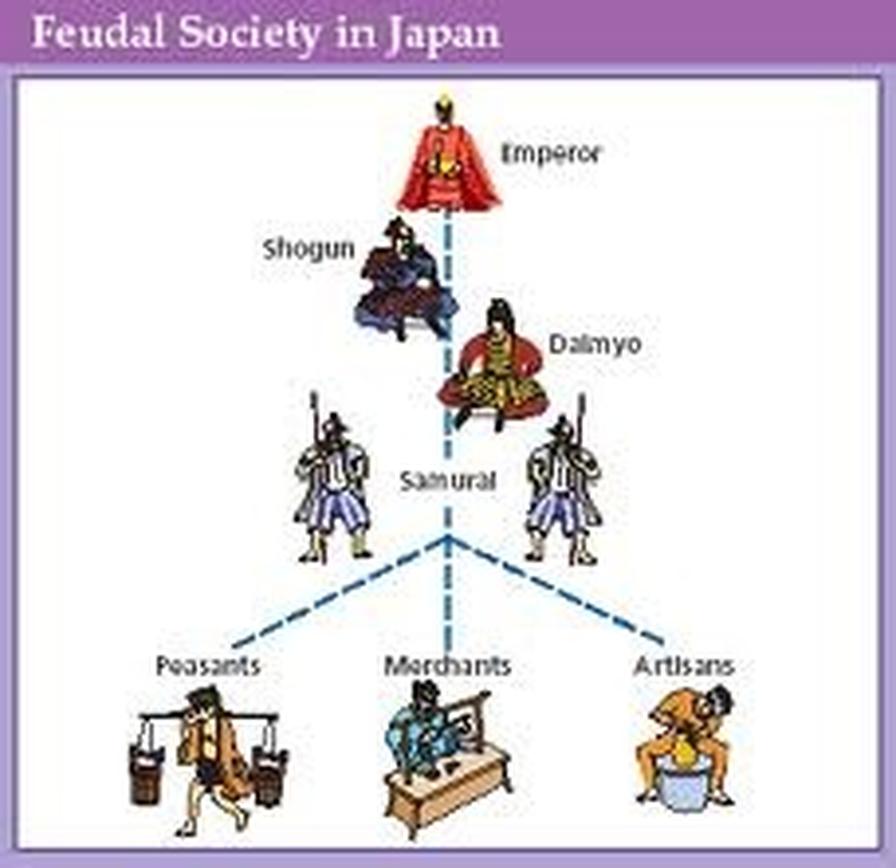

The difference between the Shogun and the Emperor in Japan lies primarily in their roles, sources of authority, and the nature of their power during Japan’s premodern era.

The Emperor held a largely ceremonial and spiritual role. The imperial family’s legitimacy rested on Shinto religion, claiming direct descent from the sun goddess Amaterasu. This belief created an irrevocable divine mandate that made the Emperor Japan’s ultimate spiritual and cultural authority. The Emperor’s duties involved court rituals that were intricately connected to governance, even if practical political control was limited. This divine status made the Emperor a symbol of legitimacy that military rulers needed but could never replace.

In contrast, the Shogun was a military leader who held real political and military power. The Shogunate, or bakufu, emerged as the ruling military government, controlling land administration, taxation, and military affairs. The first lasting Shogunate was the Kamakura Shogunate (1189–1333), which ruled Japan by managing its military retainers and landholdings on behalf of absentee aristocrats, including the Emperor. Although the Shoguns exercised effective control over Japan’s governance, they derived their legitimacy from the Emperor’s sanction. Their authority was contingent upon the imperial court’s recognition and the cultural legitimacy it conferred.

The two authorities operated in intersecting spheres of power. The Emperor’s legitimacy was tied to spiritual and ritual functions, while the Shogun managed practical matters like governance, land, and military command. The Shoguns never entirely eclipsed the Emperor because their power was fragile and subject to the support of warrior families (daimyos). Their dominance depended on military strength and alliances, making their rule more precarious.

Historically, the Shogunate periods—primarily Kamakura and Muromachi (1336–1573)—illustrate this dynamic. Both regimes centered their governments in different locations but maintained the dual structure of government: the Emperor’s court performing ceremonies and conferring legitimacy, the Shogun controlling practical governance and military affairs. For example, Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, the 3rd Muromachi Shogun, exerted more overt political dominance and even influenced imperial rituals. Despite this, attempts to replace the imperial family, such as his efforts to have his son declared Emperor, were unsuccessful. The entrenched religious belief in the Emperor’s divine right kept the imperial line unbroken.

The Tokugawa Shogunate (1600–1868) further institutionalized military control while carefully managing the imperial family. Tokugawa rulers controlled powerful feudal lords by mandating their long-term presence in the capital, a tactic to prevent rebellion. They also married into the imperial household but never usurped the Emperor’s position. This reinforced the separation of military governance from the sacred imperial status.

Land management and taxation evolved under these dual systems. While the imperial court initially claimed ownership over land based on Chinese models, this system quickly fragmented. Aristocrats, temples, and shrines held land but depended on local military leaders for administration. The Shogunate effectively administered these lands via their military retainers, collecting taxes and maintaining order. Thus, the Shogun controlled the economic engine, while the Emperor maintained symbolic ownership and spiritual authority.

The Shogun’s power was inherently tenuous. As the leading daimyo, they had to maintain military superiority and manage a delicate web of loyalty among other powerful feudal lords. This required constant vigilance and political skill. Their legitimacy rested on the Emperor’s sanction, but their survival depended on military dominance and governance.

In summary:

- The Emperor held supreme spiritual authority, legitimized by Shinto beliefs and rituals.

- The Shogun exercised actual political and military power, acting as the de facto ruler.

- Shogun legitimacy stemmed from imperial sanction, making both roles interconnected.

- Over approximately 600 years, various Shogunates balanced governance and ceremonial authority differently.

- Attempts by Shoguns to replace the Emperor failed due to the deep-rooted religious and cultural legitimacy of the imperial family.

- The Tokugawa Shogunate controlled feudal lords tightly and maintained a complex relationship with the Emperor.

- Land and taxation were managed by military leaders under aristocratic and imperial auspices.

Difference Between the Shogun and the Emperor in Japan: Untangling Two Intersecting Powers

In Japan’s premodern history, the Shogun and the Emperor were heads of two intersecting spheres of authority, each wielding distinct powers and roles that shaped the nation’s governance for centuries. But what exactly sets these two apart, and why does this difference matter more than a simple label?

Let’s peel the layers off this historical onion, revealing a story richer and more complicated than most quick summaries can do justice.

Why Oversimplification Won’t Cut It

The common narrative portrays the Emperor as a weak figurehead and the Shogun as the de facto ruler. This may sound neat, but it’s a tidy myth that overlooks nuance. First off, the shogunate system lasted roughly 600 years, spanning eras with varying political climates. Narrowing down the timeline is essential to understanding shifts in power dynamics.

Also, the idea of “state” in premodern Japan isn’t our modern nation-state with defined borders and centralized governance. Authority was dispersed, overlapping, and sometimes ambiguous.

So, when you think about the difference between the Shogun and the Emperor, don’t just view it through today’s lens.

The Emperor’s Role: Divine Ceremonialist or Power Player?

In modern terms, the Emperor might look like a mere symbol. Yet, before the 19th century, that’s a dangerously misinformed view. The Emperor’s duties were largely ceremonial, true—but those rituals were the core of governance.

The Emperor was believed to be divinely legitimated through Shinto religion, descended directly from Amaterasu, the chief deity. This religious sanction created an irrevocable mandate. Think of it as Japan’s version of the Mandate of Heaven in China.

In practical terms, all government rituals, protocols, and even the concept of legitimate rule revolved around the Emperor’s spiritual status. This presence gave cultural power that even military rulers could not ignore.

The Shogun: Military Head and Power Broker

The Shogun’s domain was the military and political control grounded in land management and taxation. Unlike the Emperor, the Shogun directly administered lands through retainers—warriors and local lords—collecting taxes and maintaining order.

The Kamakura (1189-1333) and Muromachi (1336-1573) shogunates were distinct military governments with fluctuating relations with the imperial court. Each maintained control over different regions and possessed varying degrees of autonomy.

However, the Shogun’s legitimacy was still granted by the imperial court. Despite their economic and martial power, the Shoguns derived official sanction from the Emperor, who remained Japan’s ultimate source of authority in terms of cultural and religious legitimacy.

How Land and Power Intertwined

Originally, the imperial court borrowed the Tang system, where the Emperor owned all land and delegated usage rights. This system quickly faded beyond the capital region, leading aristocratic families, shrines, and temples to claim taxation rights.

These groups hired local martial leaders to govern the lands—enter the Shogun and his warriors. They became the de facto administrators, bridging the gap between absentee landowners and the peasants.

Thus, the Shogun’s role evolved into a military governor managing decentralized land domains, differing from the Emperor’s theoretical ownership and spiritual authority.

A Shogun’s Legitimacy Always Hangs on a Thread

Despite the Shogun’s military might, their power was surprisingly fragile. The office was essentially the strongest Daimyo among many, securing dominance through force rather than tradition.

Because loyalty was unreliable and daimyo power always threatened, Shoguns needed the Emperor’s sanction to legitimize their authority. This dependency explains why outright deposition of the Emperor was out of the question—they couldn’t risk undermining the source of their legitimacy.

Ashikaga Yoshimitsu: When the Shogun Almost Became Emperor

Occasionally, the power lines blurred. Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, the third Muromachi Shogun, managed to cast himself almost as a military dictator. He participated in court rituals, a rare move signifying deep influence. Some scholars suggest his heir might have claimed the throne, had circumstances allowed.

He even became a vassal to the Ming Emperor, styled “King of Japan,” not Emperor. Attempts to elevate his family to imperial status failed, illustrating the limits placed on shogunal power—no matter how strong.

The Tokugawa Shogunate’s Masterclass in Control

Fast forward to the Tokugawa period: the shoguns devised a clever way to maintain power. They required daimyo families to spend much time in Edo, the capital, limiting their ability to marshal resistance—like a 17th-century “you sit here and behave” strategy.

The Tokugawas also intermarried with the imperial family, not to become emperors themselves, but to gain another lever of control over the court. This subtle dance kept the Emperor’s cultural power intact while securing Tokugawa dominance.

Why Couldn’t the Shogun Just Take Over?

The Shogun’s refusal or inability to depose the Emperor wasn’t just politeness—it was structural and spiritual. The Emperor’s role as the theocratic and cultural centerpiece of Japan’s political order was untouchable.

As long as Shinto was believed—and it remains influential—the imperial lineage was seen as divinely ordained. The Shogun’s power was practical, more brute force, but without the Emperor’s spiritual legitimacy, it was hollow.

Intersecting Spheres, Not Overlapping Thrones

Think of the Emperor and Shogun as co-rulers of different realms: the Emperor embodied spiritual and ceremonial sovereignty, legitimizing the state’s moral foundation. The Shogun managed military power and land governance—the nuts and bolts of daily rule.

One without the other would have left a kingdom without its heart or muscles. Together, even with occasional power struggles, they formed a unique balance.

What Can We Learn from This Ancient Power Dance?

Japan’s political history teaches us that authority isn’t just about might or titles but about beliefs and traditions people uphold. The Shogun’s strength was undeniable but unstable. The Emperor’s power seemed symbolic but anchored society’s legitimacy.

Does this remind you of any modern politics where leaders must maintain appearances and cultural backing to truly rule? Probably, yes.

So next time you hear the words “Shogun” and “Emperor,” remember: it’s not a simple game of king versus general. It’s two intertwining stories of power, faith, and survival across centuries.

Summary Table: Quick Glance at Shogun vs Emperor

| Aspect | Emperor | Shogun |

|---|---|---|

| Role | Spiritual and ceremonial ruler, divine legitimacy | Military leader, de facto political ruler |

| Power Source | Descendant of Amaterasu, Shinto religious sanction | Military strength, Daimyo alliances, sanctioned by Emperor |

| Governance | Ceremonial rituals central to legitimacy and state order | Land administration, taxation, military control |

| Political Stability | Stable cultural symbol, impossible to replace | Tenuous, reliant on military dominance and court legitimation |

| Examples | Dynastic rule backed by Shinto beliefs | Shogunates: Kamakura, Muromachi, Tokugawa |

Wrapping Up

The difference between the Shogun and the Emperor in Japan lies in their foundations—one spiritual, the other practical. Both powers shaped Japanese history, not through direct conflict, but through delicate coexistence and mutual dependence.

Understanding this helps demystify premodern Japan’s governance and enriches our comprehension of how culture and power intertwine. It reminds us that history often resists simple answers.