The Hanging Gardens of Babylon represent one of antiquity’s most enigmatic wonders, with no definitive proof confirming their actual existence or precise location. While historical texts laud them as lavish, tiered gardens employing advanced irrigation, archaeological evidence to support these accounts remains absent, particularly within Babylon itself.

Historical consensus accepts that ancient Mesopotamian rulers built remarkable royal gardens incorporating sophisticated water systems. Writers like Diodorus Siculus and Philo of Byzantium describe elaborate irrigation techniques supporting such gardens, indicating the technological capacity existed. However, these accounts vary widely and sometimes conflict, suggesting they may aggregate tales of different gardens from diverse regions rather than a single “Hanging Gardens” in Babylon.

One compelling theory challenging the traditional Babylonian location arises from Stephanie Dalley, an Assyriologist formerly at Oxford University. Dalley contends that the Hanging Gardens were actually situated in Nineveh, the Assyrian capital under King Sennacherib (reigned 705–681 BC). She argues that the classical attribution of the gardens to Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon results from later confusion among ancient writers rather than firm historical fact.

Dalley bases her hypothesis on several factors:

- Babylonian inscriptions and archaeological findings do not mention or reveal evidence of the Hanging Gardens, despite Nebuchadnezzar’s extensive building records.

- Classical authors who describe Babylon, including Herodotus and Xenophon, do not mention gardens, though they detail other notable city features.

- Sennacherib left detailed records of engineering efforts to channel mountain water to Nineveh, providing irrigation for extensive gardens near his palace.

- A sculptural relief at Nineveh, from Sennacherib’s successor Assurbanipal, visually depicts lush terraced gardens traversed by water channels, resembling classical descriptions of the Hanging Gardens’ tiered structure.

Dalley suggests that during Sennacherib’s reign, he destroyed Babylon and briefly ruled it, with Nineveh possibly known as a “New Babylon,” possibly fueling later confusion in the Greek and Jewish traditions merging Nineveh’s gardens with Babylon’s legacy.

The major classical descriptions of the Hanging Gardens derive from authors far removed from Babylon and Assyria in time and place. For instance:

- Philo of Byzantium, a technical writer from the 3rd century BC, described irrigation but is vague on primary sources.

- Diodorus Siculus (1st century BC) cited Ctesias, an often unreliable 5th-century BC historian.

- Strabo (1st century AD) referenced secondhand accounts without visiting Babylon.

- Josephus (1st century AD) drew from Berossus, a Babylonian priest writing in Greek in the 3rd century BC.

- Quintus Curtius Rufus (1st century AD) relied on late 4th-century BC historians who themselves compiled earlier reports.

None of these authors personally saw the gardens, and their descriptions passed through translations and retellings, creating a “Chinese whispers” effect. The Greeks often confused Babylon with Nineveh and mixed up rulers and timelines, leading to historical inaccuracies. Even biblical texts interchange Babylon and Nineveh mistakenly.

No contemporary Mesopotamian text from Nebuchadnezzar’s era mentions gardens matching the famous wonder, which is unusual given his habit of documenting construction projects exhaustively. Moreover, no confirmed archaeological remains corresponding to the Hanging Gardens have emerged at Babylon. Some scholars speculate that evidence may be buried beneath the Euphrates River, which shifted its course over millennia, complicating excavations on the western side of Babylon where the gardens are traditionally placed.

Dalley’s view, while intriguing, is not universally accepted. The Nineveh gardens could represent the inspiration for the legend rather than the actual Hanging Gardens. Other Assyrian sites also showcase impressive gardens with complex water engineering, such as those near Nimrud, where giant irrigation projects supported vast palatial landscapes under King Assurnasirpal II.

In sum, the lack of direct archaeological evidence, the absence of contemporaneous Babylonian textual references, and the confusion in classical sources contribute to the Hanging Gardens uniquely remaining the only one among the Seven Wonders whose exact existence and location are not definitively established.

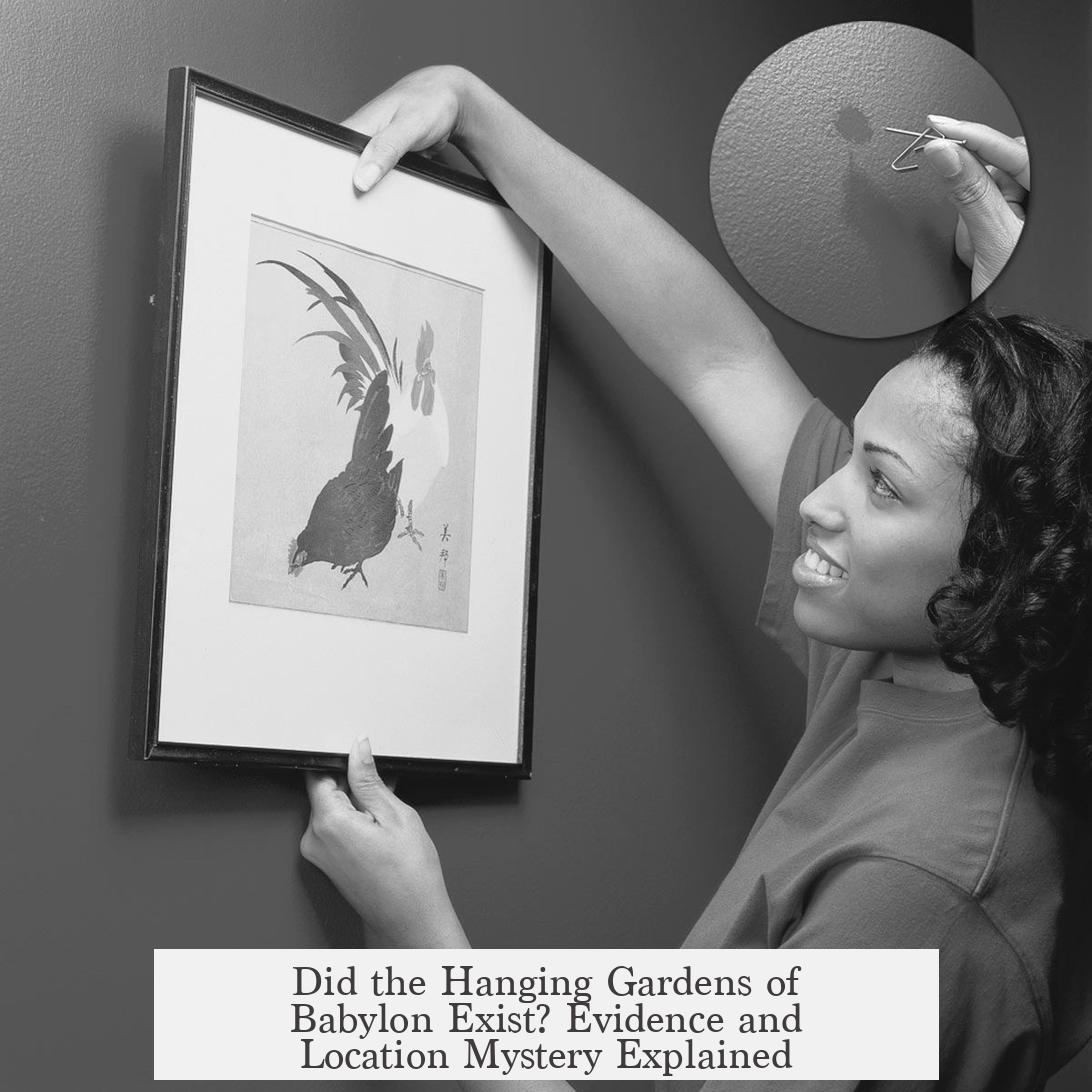

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Historical Descriptions | Come from authors who never visited Babylon; second or third-hand accounts; often conflicting and vague. |

| Archaeological Evidence | None found in Babylon; some reliefs in Nineveh depict terraced gardens with irrigation. |

| Alternate Theory | Stephanie Dalley identifies Hanging Gardens with Sennacherib’s gardens in Nineveh, not Babylon. |

| Why No Definitive Location? | River course changes; no conclusive Babylonian texts; classic sources confuse cities; potential lost evidence underwater. |

Key takeaways:

- The Hanging Gardens commonly attributed to Babylon lack definitive archaeological proof.

- Classical literary sources are secondhand and sometimes contradictory about location and builder.

- Stephanie Dalley’s theory locates the gardens in Nineveh, based on Assyrian records and art.

- Shifts in the Euphrates and gaps in Babylonian records explain the missing evidence.

- The confusion between Babylon and Nineveh in ancient texts contributes to the unresolved mystery.

Did the Hanging Gardens of Babylon really exist?

The consensus is that such gardens existed, as ancient texts describe elaborate royal gardens with advanced watering systems. However, it is unclear if the famous Hanging Gardens were a single, specific site or a mix of stories about different gardens in the region.

Why has no definitive proof been found at Babylon?

Archaeological evidence and local cuneiform texts from Babylon do not mention the gardens. King Nebuchadnezzar’s inscriptions, which detail his building projects, do not refer to any gardens. This absence raises doubts about their presence in Babylon itself.

What is Stephanie Dalley’s theory about the gardens’ location?

Dalley suggests the gardens were in Nineveh, built by Assyrian king Sennacherib. She argues classical authors confused Babylon with Nineveh, noting that Sennacherib’s records describe advanced gardens and irrigation systems fitting the traditional descriptions.

Why do classical sources give conflicting descriptions of the gardens?

Ancient writers never visited Babylon and relied on secondhand reports. Many mixed up city names and historical details, often confusing Nineveh with Babylon. Their accounts spread through multiple languages, leading to errors and overlaps.

Which ancient authors described the Hanging Gardens?

- Philo of Byzantium described the watering methods.

- Diodorus Siculus quoted earlier sources but was sometimes unreliable.

- Strabo based his account on reports from Alexander the Great’s officers.

- Josephus referenced a Babylonian priest’s history.

- Quintus Curtius Rufus derived information from near-contemporary sources.

Why is the Hanging Gardens the only Wonder whose location remains uncertain?

Unlike other Wonders, no direct archaeological site or reliable first-hand account links conclusively to the gardens in Babylon. Misplaced geographical references and lack of physical traces contribute to the ongoing mystery about their exact site.