The Confederacy did not have a realistic path to victory in the American Civil War. Despite some early successes and hopes for foreign intervention or Northern political shifts, significant strategic disadvantages and resource imbalances made Confederate victory highly unlikely from the start. Key factors such as manpower, industrial capacity, naval strength, and geography overwhelmingly favored the Union. The Confederate attempts to invade the North ended in failure, and foreign powers refused to intervene after the war became clearly tied to ending slavery. The South’s strategy to pressure the North politically through battlefield successes was impractical given these conditions. Ultimately, Confederate defeat was inevitable once Union military leadership improved and major territorial and logistical control passed to the North.

The Confederacy’s aim was not to conquer the North but to secede and maintain their slaveholding society. They did not aim to reunify the nation as a slave country, which was an impossible goal considering the North’s population and resources. Union forces decisively repelled Confederate invasions like those at Antietam and Gettysburg. Holding onto Confederate territory was difficult enough; launching a full-scale conquest of a bigger and better-equipped North was never feasible.

The initial Southern military successes, such as at the First Battle of Bull Run, fueled Southern hopes but masked underlying strategic weaknesses. The Confederacy benefited early on from Union leadership struggles. President Lincoln replaced ineffective generals until he found commanders who leveraged Union advantages effectively. Once competent Union leadership emerged, Confederate defeats increased steadily.

Hope for foreign intervention—especially from Britain and France—dwindled after the Emancipation Proclamation. Britain’s public opinion largely opposed slavery, and any intervention would have meant costly war with the United States. Political realities made it impossible for foreign powers to support the Confederacy once the war’s abolitionist cause was clear.

The Southern strategy focused on imposing enough battlefield costs to force Northern politicians into peace negotiations. This strategy had some merit early on because Southern politicians believed Northern voters might tire of war and elect leaders favoring peace. However, this assumption underestimated Northern resolve and the Union’s ability to replace military leadership and sustain the war effort despite heavy losses.

Several strategic disadvantages worked against the Confederacy:

- Manpower: The Union had about 2.1 million eligible men compared to roughly 800,000 in the Confederacy.

- Industry: The North employed approximately 1.3 million industrial workers; the South had about 110,000 at the war’s start.

- Logistics and transportation: More advanced in the North, aiding troop movements and supply.

- Naval supremacy: The Union controlled naval forces and shipbuilding capacity. Major Confederate port cities were indefensible.

- Geographic advantages: The Mississippi and other rivers bolstered Union control and split Confederate territories.

The loss of key cities such as New Orleans, which housed major shipyards, crippled Confederate naval capabilities early. The U.S. Navy controlled the rivers and blocked Confederate ports, further isolating the South and cutting off trade and supplies.

One potential Confederate hope lay in the 1864 U.S. presidential election. The South wished for Lincoln’s defeat and hoped a new administration might seek peace. However, this scenario was unlikely. General George McClellan, Lincoln’s opponent, campaigned on continuing the war to preserve the Union, not surrendering to the Confederacy. The capture of Atlanta by Union forces in 1864 further boosted Northern morale and assured Lincoln’s reelection.

After the turning of the war’s tide in favor of the Union, events such as Sherman’s march through Georgia, the fragmentation of Confederate armies, and the control of the Mississippi River made Confederate defeat all but certain. Jefferson Davis and other Southern leaders viewed the conflict as a defense of their entire way of life, but continuing to fight as military options dwindled caused unnecessary suffering.

| Factor | Union (U.S.) | Confederacy (CSA) |

|---|---|---|

| Manpower | Approx. 2.1 million | Approx. 800,000 |

| Industrial workers | Approx. 1.3 million | Approx. 110,000 |

| Major shipyards | Accessible and secure | Concentrated in vulnerable cities (New Orleans, Norfolk) |

| Naval power | Sole naval and shipbuilding force at outset | None, reliant on captured vessels |

| Geography | Control of major rivers and interior lines | Fragmented territory separated by rivers under Union control |

The “Lost Cause” narrative sometimes exaggerates Confederate chances of winning, focusing on battlefield successes while downplaying structural advantages held by the Union. The South never recovered from the initial strategic deficits. Their battlefield prowess delayed defeat but did not provide a realistic path to victory.

- The Confederacy lacked sufficient manpower and industry to sustain a long war.

- Union naval and geographic advantages allowed for blockades and division of Confederate territory.

- Foreign intervention was politically impossible after abolition became a Union war aim.

- The South’s hope of Northern political fatigue underestimated Union resolve and military adaptation.

- Confederate military successes were often due to Union leadership weaknesses, which were later corrected.

Did the Confederacy Ever Have a Realistic Path to Victory?

The short and sharp answer: no, the Confederacy never had a realistic path to victory in the American Civil War. While the Confederacy fought bravely, several deep, strategic flaws made their ultimate defeat all but inevitable. Let’s unpack why, exploring their military, political, and logistical challenges, and how the Union’s superior resources and leadership steadily crushed Southern hopes.

The Confederacy’s Ambition: Not to Conquer But to Secede

First, it’s important to clarify what the Confederacy wanted. *They were not trying to conquer the North.* The South’s goal was secession—to break away from what they saw as hostile and abolitionist northern control. Their battle wasn’t to unite a nation under slavery but to preserve their own slaveholding states independently. Ambitious attempts to invade the North, like the battles of Antietam and Gettysburg, ended disastrously for the South, confirming that conquering the far more populous and industrial North was out of the question.

Think about it: the Confederates faced a population mismatch of roughly 800,000 men versus the Union’s 2.1 million. How does one win a war with less than half the manpower? They couldn’t. Their early victories were sometimes enough to shake the Yankees but hardly to push them back permanently. The Confederacy could barely hold their territory, much less dream of expansion.

Southern Strategy: Threaten, Bleed, and Negotiate

The Southern game plan was to “bleed the North” to the point of exhaustion—force blood, sweat, and tears so deeply that Union morale would fracture politically. The hope was that enough casualties would lead to Abraham Lincoln’s defeat in the 1864 election, bringing in a new President like George McClellan, who might negotiate peace favorable to the South.

Here’s the catch: this was a colossal gamble. It banked entirely on the North’s political will crumbling and a soft approach emerging. But it ignored Lincoln’s steadfast commitment to Union preservation, especially after he made the war about ending slavery with the Emancipation Proclamation. By then, foreign support, which the Confederacy desperately needed, was out of the question.

Foreign Intervention? A Pipe Dream

The South pinned some hope on countries like Britain and France coming to their aid. At first glance, this seemed plausible. England had major cotton interests, and France had ambitions in the Americas. However, once Lincoln framed the conflict as a fight to end slavery, foreign governments—particularly Britain’s strongly anti-slavery public—could no longer support the Confederacy openly.

Entering a costly war with America to back a pro-slavery rebellion was politically impossible for Britain and France. So any ‘help from abroad’ faded into a historical fantasy.

Union Leadership: The Turning Point

One major reason the war went on as long as it did was Union leadership, or rather the early lack of effective leadership. Early Union generals stumbled against the surprise and tactical skill of Confederate commanders like Robert E. Lee. However, Lee’s military “genius” owes much to his opponents’ failings. Lincoln struggled for years cycling through commanders until he found leaders who matched the Union’s overwhelming advantages with effective strategy.

Once leaders like Ulysses S. Grant took the helm and aggressively leveraged the North’s vast troop numbers, industrial production, and transportation infrastructure, Confederate defeats piled up.

Industrial and Manpower Imbalance: The Real Deciders

In war, numbers and supplies count. The North’s advantage was staggering—about 1.3 million industrial workers versus the South’s 110,000 at the war’s start, and more than double the manpower. This wasn’t just a “nice to have”; it translated into more weapons, supplies, and reinforcements.

The Confederacy could craft courageous battles but couldn’t sustain a lengthy war against a giant economic engine. The South’s infrastructure was fragile: major cities like New Orleans and Norfolk were undefensible and quickly fell to Union forces. These cities housed nearly 40% of Confederate shipyards—once gone, so was the South’s naval capability.

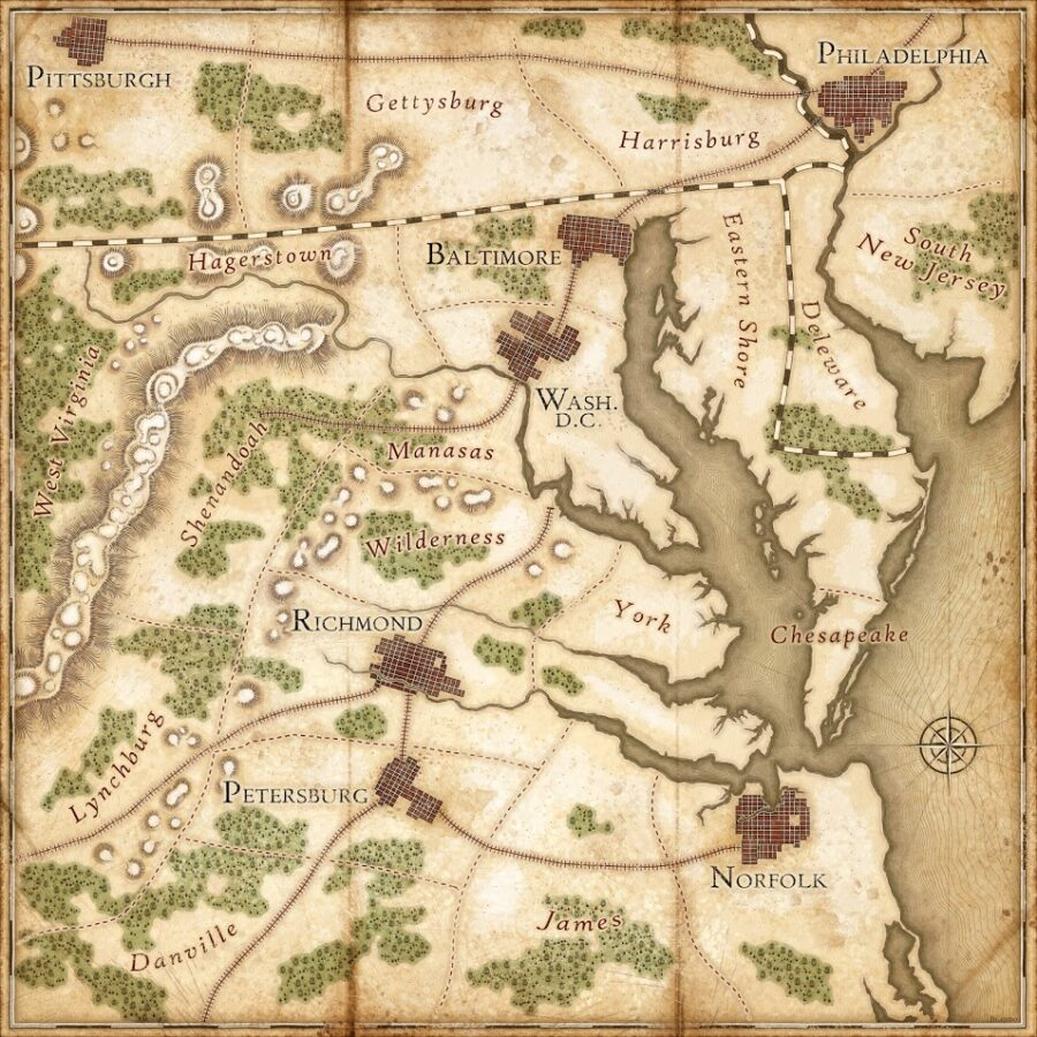

Geographical Challenges and River Control

Geography didn’t favor the South either. Major rivers, like the Mississippi, Cumberland, and Tennessee, fed into the Confederate heartland from Union-controlled territory. The North’s superior navy and river access allowed blockades that strangled Southern ports, halting vital supplies and trade.

Once the Mississippi River fell under Union control, the Confederacy was split, cutting off states from supporting each other. This geographical disadvantage sealed Confederate fate in ways their brave armies could not overcome.

The Fatal Endgame: When Defeat Became Inevitable

By 1864, all signs pointed to Confederate defeat. After General Sherman’s Atlanta campaign crippled the South’s strategic heart and Hood’s army was shattered, the Confederacy was surrounded and strangled. The Mississippi system was closed off, ports blockaded, and manpower and morale all but shattered.

People like Jefferson Davis still believed they were defending a divine and perfect Southern society, but facts on the ground told another story. With no realistic chances for reversals, continuing to fight was arguably a futile exercise leading to needless bloodshed. Yet, the Confederacy pressed on out of belief and desperation, not possibility.

The Lost Cause and War Mythology

Over time, the myth of the Lost Cause glamorized Confederate bravery and hinted at “what could have been.” This narrative overstates battlefield successes and glosses over strategic realities. Tactical victories on the field couldn’t overshadow fundamental disadvantages present from the war’s start.

Many argue Confederate hopes ignored logistics and scale. In reality, victories were fleeting moments in a larger, overwhelming tide of Union strength.

Did Northern Politics Offer a Backdoor Victory?

Could the South have won by outlasting Northern political resolve? In theory, yes. But this requires two massive assumptions: that Lincoln’s morale-crushing would fail, and that McClellan would then negotiate peace. Oddly, McClellan campaigned on finishing the war, not ending it through negotiation. Therefore, relying on Northern voters turning decisively away from the war effort was a long shot.

After the fall of Atlanta, Northern morale surged and Lincoln’s re-election became inevitable. The Confederate strategy collapsed politically as well as militarily.

Wrapping It Up: Why No Realistic Path to Victory Existed

- Impossible manpower and industrial disadvantages made sustaining war effort overwhelming for the South.

- Geographical vulnerabilities exposed Confederate territory to Union invasion and economic strangulation.

- Lack of foreign intervention, once the war’s anti-slavery purpose became clear, eliminated hoped-for outside aid.

- Union leadership, poor at first but improving drastically, exploited Northern strengths decisively.

- Southern political goals didn’t include conquering the North but found themselves unable to survive alone.

- Hopes pinned on politics and election shifts were based on flawed assumptions.

The Confederacy’s dream of victory was always a high-stakes gamble. No combination of battlefield brilliance, foreign aid, or political upheaval realistically promised success against an opponent with superior numbers, resources, and a determined leadership. The “Lost Cause” might sound romantic, but it remains a myth when confronted with the strategic facts.

Want to Dive Deeper?

Reading firsthand accounts of Confederate leaders’ speeches, like Jefferson Davis’, reveals how their mindset clung to an impossible world. Imagine fighting for a future you believe must exist, even in the face of overwhelming odds. It’s tragic, brave, and ultimately doomed.

So next time the question pops up—*Did the Confederacy ever really have a clear path to victory?*—remember: Their victories were sparks in a storm of insurmountable disadvantages. The real question might be: How did the South last as long as it did?