Yes, the Athenians had a genuine shot at winning the Peloponnesian War. Multiple factors, including Sparta’s willingness to negotiate peace and Athens’ inherent advantages, suggest victory was within reach. However, a series of strategic errors, internal conflicts, and external pressures led to Athens’ eventual downfall.

Sparta offered peace terms several times, notably in the war’s final four years, even after Athens suffered setbacks like the plague and the disastrous Sicilian Expedition. Athens refused these offers, pressing on with hopes of a complete victory instead. This refusal reflected Athenian societal values at the time, which celebrated competition and toughness. Peace was seen as unmanly and potentially a sign of weakness or doom. Thus, Athens’ cultural mindset shaped its decision to reject peace and continue fighting.

Athens’ advantages over Sparta were significant. It was wealthier and held stronger control over its allies through the Delian League. Its population was comparable in size to Sparta’s, but Spartan citizens constituted a smaller fighting force since much of their population were helots, essentially enslaved people. Athens, therefore, had greater resources and a larger pool of manpower, especially for naval power.

However, Athens sabotaged itself through factional infighting and poor leadership. Alcibiades, a complex figure, first played a pivotal role in undermining peace. After promoting the Sicilian Expedition aimed at crippling Sparta’s food supply by attacking Syracuse, Alcibiades fled to Sparta when the campaign faltered. He then advised Sparta on how best to counter Athens. This betrayal significantly harmed Athens’ war efforts.

| Event | Impact |

|---|---|

| The Sicilian Expedition | Complete loss of an entire Athenian force, including many citizens, weakening military strength. |

| Athenian plague (430 BC) | Killed approximately 25% of population and leadership, devastating morale and manpower. |

| Alcibiades’ political maneuvers (411 BC) | Opened the door for oligarchic rule, undermining Athenian democracy and unity. |

The plague of Athens critically weakened the city-state, severely reducing its manpower and morale. This prevented Athens from mounting effective offensives for years. Additionally, Alcibiades’ influence led to political instability. He conspired with Critias, a prominent oligarch, to overturn democracy in 411 BC, creating an oligarchic regime that destabilized Athens further.

Despite these setbacks, Alcibiades also won major naval victories against Sparta and its allies. Ironically, he was removed from command after losing 25 ships in a storm, and his successors lacked his skill. This leadership vacuum contributed to Athens’ eventual defeat.

The strategic challenge of the war lay in its asymmetry. Athens dominated the sea, controlling coastal and island allies who contributed funds more than soldiers. Sparta, a land power, relied on foot soldiers from its Peloponnesian allies. Athens aimed for a decisive victory but perhaps overstretched itself by trying to crush a land-based power with primarily naval strength. This strategic overreach proved problematic.

It is also important to note that Sparta’s victory didn’t grant it uncontested rule over Greece. Sparta’s dominance depended heavily on Persian support and waned after the Corinthian War (395-387 BC). Their power diminished further following their defeat by Thebes at Leuctra in 371 BC, signalling the end of Spartan hegemony.

The Peloponnesian War illustrates how victory depended not just on military might but also on leadership, internal politics, strategy, and external conditions. Athens’ failure to seize peace opportunities, its cultural fixation on competition and total victory, internal dissension, disease, and leadership mistakes all combined to squander a potentially winnable war.

- Sparta offered peace multiple times; Athens consistently refused.

- Athens held advantages in wealth, population, and naval power.

- Internal political strife and leadership failures weakened Athens.

- The plague decimated Athens’ population and morale.

- Strategic overreach by Athens aimed to crush a stronger land power at sea.

- Spartan dominance after the war was fragile and ultimately temporary.

Did the Athenians have a shot at winning the Peloponnesian War at all?

Absolutely, the Athenians did have a shot at winning the Peloponnesian War. In fact, many moments during the conflict showcased Athens’ potential advantage and missed chances. Understanding Athens’ opportunities and decisions reveals a complex story of power, pride, and strategic blunders.

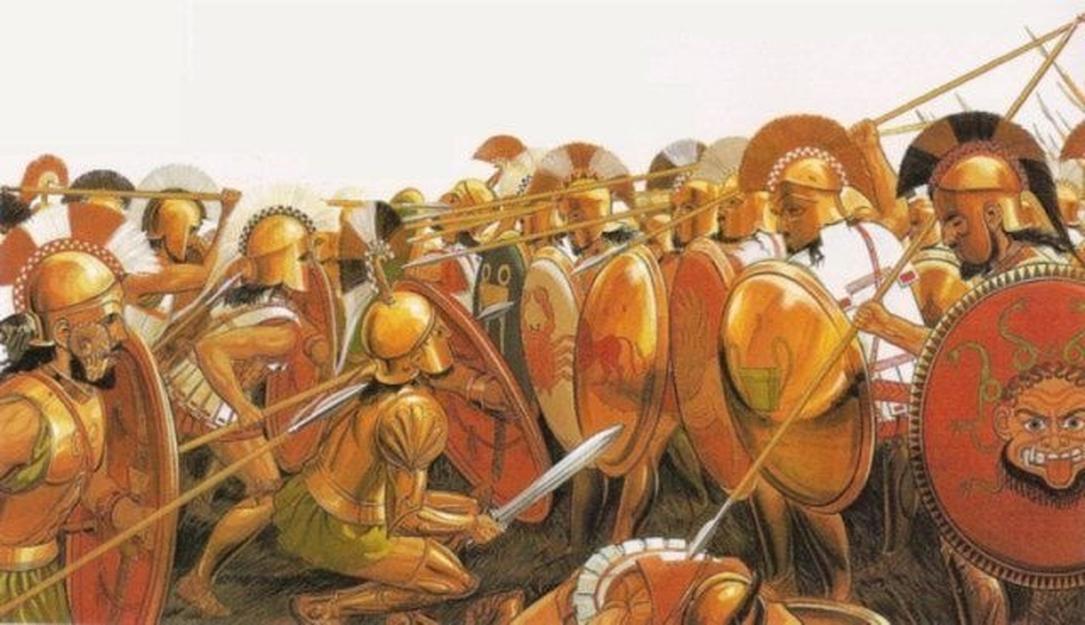

Before diving deeper, let’s set the stage. The Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC) was a brutal clash between Athens and Sparta, two Greek superpowers. Yet, this wasn’t a simple contest—Athens ruled the seas, Sparta dominated the land, and their very different strengths shaped a war of attrition, shifting alliances, and intense struggle.

The Fine Line Between Victory and Defeat: Athens’ Advantages and Missed Peace Deals

Athens wasn’t just any city—it was a wealthy maritime empire. Its population was comparable to Sparta’s, but a key difference was that most Spartans were supported by a large enslaved population who could not fight, limiting Sparta’s military manpower. Athens, controlling a vast network of coastal and island allies, wielded more economic power and had more direct control over its allies than Sparta.

At critical points during the later stages of the war, Sparta wanted peace. For four years in the final stretch, even after major setbacks for Athens like the plague and the disastrous Sicilian expedition, Sparta approached Athens with peace proposals. Yet, Athens repeatedly said a firm “no.” Why did Athens refuse peace multiple times? This decision wasn’t simply stubbornness but deeply tied to their identity.

In Athenian culture, peace was unmanly. Their society revolved around competition—in business, sport, and politics. Laws were like sports plays; their authors had to defend them publicly, even if flawed. A famous Athenian play mocked peace as an act brought about by wives’ sexual boycott—fueling the belief peace means weakness. So the Athenian leaders pushed for total victory, convinced that outright conquest was feasible.

Even after Athens won a key naval battle at Cyzicus post-Sicilian disaster, Sparta offered peace on equal terms. Athens turned it down again. These moves suggest Athens believed it could decisively win, not just survive. So yes, they had a real shot — but pride and competitiveness overwhelmed pragmatism.

Leadership Drama: Alcibiades and Strategic Blunders That Tugged Athens Back

If Athens had a secret weapon, it was Alcibiades—part genius, part drama magnet. Known as a student of Socrates and a lover of drama (both kinds), Alcibiades played a messy role. After peace was agreed, he schemed to undermine it, persuading Athens to invade Syracuse, akin to trying to conquer the ancient world’s Britain.

This Sicilian expedition was a disaster. Nicias, another Athenian commander, wasted time dithering when Syracuse was vulnerable. Eventually, Athens lost the entire force there, a significant chunk of their manpower gone at once. Alcibiades later fled to Sparta, advising their enemies on how to beat Athens, demonstrating how high the stakes—and betrayals—were.

Alcibiades then returned, helped install an oligarchy alongside Critias—again a student of Socrates—and convinced the wealthy that democracy had failed. Soon, a faction of armored rich men, able to afford gear, repealed illegal laws and set up oligarchy, alienating many Athenians.

Oddly, Alcibiades had some bright moments later. As general, he forced many Spartan allies to surrender and won key naval battles. Yet, after losing 25 ships in a storm, he was kicked out. The successors? Not so competent. This lack of consistent leadership proved costly to Athens.

The Plague: A Deadly Blow Athens Could Not Shake

Let’s not forget the plague—the grim wildcard no general chooses. In 430 BC, it wiped out about a quarter of Athens’ population, including crucial leaders. morale plunged, and Athens could not maintain offensive campaigns for years. This disaster wasn’t just about numbers; it shattered Athenian confidence and weakened strategic options.

Asymmetric Conflict: A Clash of Sea and Land Powers

The war pitted two very different forces. Athens ruled at sea, relying on wealth and coastal allies providing money. Sparta was a robust land power, backed by soldiers from its surrounding Peloponnesian cities.

Athens’ strength was mostly maritime. Trying to eradicate a land-based power through naval dominance had limits. Arguably, Athens overreached in aiming for total crushing victory against Sparta, ignoring how hard it is to win a protracted land war from the sea. This fundamental strategic mismatch complicated Athens’ path to a clear win.

Aftermath: Sparta’s Short-Lived Hegemony

Many imagine Sparta ruling all of Greece unchallenged after their victory in 404 BC, but that’s not quite right. Their control required Persian support and was far from absolute, especially after the Corinthian War. Sparta lost much prestige and faced fierce rivals like Thebes, which crushed Spartan power at the Battle of Leuctra in 371 BC. The Spartans’ heavy casualties and small citizen base made such losses crushing. Unlike the once big empire Athens ruled, Spartan dominance was fragile and short-lived.

So, Did the Athenians Have a Shot at Winning?

- Yes. Athens had the resources, the navy, and opportunities to end the war favorably multiple times.

- They >= refused peace deals, driven by cultural pride and a desire for total victory.

- Leadership mistakes—especially the Sicilian expedition—destroyed their manpower and morale.

- Internal politics and factional strife weakened unity and decision-making.

- The plague dealt a heavy blow to their population and command structure.

What if Athens had accepted Spartan peace proposals? They might have maintained their empire and avoided ultimate defeat. What if Alcibiades had not screwed around by defecting and stirring political chaos? Athens’ fate might have been brighter.

In the end, the war was as much about character and culture as about fleets and soldiers. Athens’ commitment to competition over compromise and the unpredictability of leadership choices shaped their downfall. But the fact that Sparta came begging for peace repeatedly proves Athens did have a real, if difficult, shot at victory.

Lessons From Athens’ Triumph and Tragedy

Modern strategists and students of history can learn from Athens’ story. Victory is not just about power but about choosing when to fight, when to negotiate, and avoiding overreach. Cultural attitudes and internal unity play pivotal roles. Even a dominant power can crumble when pride blinds common sense.

So next time you ask, “Did the Athenians have a shot at winning the Peloponnesian War?” remember: they had more than a shot—they had opportunities, advantages, and chances for peace that might have saved their empire. But history, as always, is a tale of what could have been.