Cults like the one portrayed in the film “Midsommar” did not exist in ancient Sweden as isolated entities, but elements of ritualistic practices, including human sacrifices, were part of broader pre-Christian Scandinavian religious traditions. These rituals were embedded within communal religious systems rather than centered around a single cult. Ancient Swedish spirituality involved complex ceremonies, mainly linked to seasonal cycles and funerary customs, rather than the theatrical and tightly knit cultic group showcased in the film.

Records of ancient Scandinavian religion remain sparse. Few contemporary accounts survive, and those that do come from external observers or are secondhand narratives written centuries later. Scandinavians used runes primarily for brief inscriptions with minimal religious content. This lack of detailed native documentary evidence limits a full understanding of their practices.

Nonetheless, numerous sources and archaeological finds confirm that ritual sacrifices, including human offerings, occurred in ancient Sweden and neighboring regions.

- Written Accounts: The 11th-century cleric Adam of Bremen described pagan rites at the temple of Old Uppsala, including sacrifices during a festival lasting nine days. He claimed that humans, along with animals, were offered daily sacrifices. While Adam’s report may exaggerate to vilify paganism, it likely reflects some factual traditions.

- Epic Poetry: Viking Age poems like the Hávamál mention gods performing rituals and self-sacrifice, indicating ritual significance in Norse mythology and religious worldview.

- Eyewitness Descriptions: The Arab traveller Ibn Fadlan, encountering Norsemen thought to be from Sweden or Gotland in the 10th century, gave detailed accounts of a slave woman’s ritual sacrifice accompanying a chieftain’s funeral.

- Archaeological Evidence: Physical remains support these descriptions. In Birka, Sweden, an elite grave contained two decapitated individuals, probably sacrifices, placed atop a high-status burial. Other ritual deposits of weapons, animals, and possibly humans are found in bogs and lake beds.

Such sacrifices tended to accompany funerals or seasonal rites. Generally, animal offerings were more common, and human sacrifices were exceptional, reserved for significant occasions. Ritual deposits in water date back to the Bronze and even Stone Age, showing long-standing customs rather than cult-specific events.

One frequently cited but unsupported feature in “Midsommar” is the ättestupa, a supposed cliff where elderly people committed suicide to avoid burdening their families. This concept lacks historical foundation. It derives from a late Icelandic saga and was later absorbed into folklore without evidence of actual practice. Historians regard it as a myth rather than ancient Scandinavian reality.

The decline of these pagan sacrificial traditions occurred alongside the Christianization of Sweden, largely completed by the 12th century. King Inge the Elder’s resistance to pagan sacrifices reflects this religious shift, with the last known pagan blót performances dated to the late 11th century during the reign of Blot-Sven, a king briefly elevated by pagan factions opposing Christian rule.

| Aspect | Ancient Swedish Religious Practice | Midsommar Film Cult |

|---|---|---|

| Human Sacrifices | Occasional, tied to funerals and seasonal festivals | Central, frequent and dramatized ritual killing |

| Ritual Context | Community-based pagan religion, seasonal rites | Isolated cult with strict hierarchies and secret ceremonies |

| Documentation | Limited, indirect, mixed archaeological and later accounts | Fictionalized with artistic license |

| Ättestupa (Elder Suicide) | Considered a myth, unsupported by evidence | Plays a key dramatic role |

In sum, while ancient Sweden did have ritual practices that included human sacrifices, these were parts of a wider pagan religion practiced by communities rather than secret cults like the one depicted in “Midsommar”. Ritual killings were rare and occurred within a social-religious context involving seasonal cycles and funerary customs. The mythic elements, such as cliff suicides, have no basis in historical or archaeological facts.

- Pre-Christian Scandinavia practiced communal pagan rituals with occasional human sacrifices.

- Human sacrifices were connected to funerals or seasonal festivals, not isolated cult activities.

- Accounts of cliff suicides (ättestupa) are unsupported and regarded as myth.

- Christianization ended these pagan rituals by the 12th century.

- Records come from foreign writers, poems, sagas, and archaeological findings, each with limitations.

Did Cults Like the One in Midsommar Exist in Ancient Sweden?

Short answer: No, cults like the one in the movie Midsommar did not exist in ancient Sweden, but ritual sacrifices and pagan religious practices certainly did—though much less theatrically and with less horror movie flair.

If you’ve seen Ari Aster’s unsettling film Midsommar, with its strikingly bright but twisted cult life set in Sweden, you might wonder if something like that ever really existed. The film creates a vivid, cinematic cult with sun-dappled ceremonies, human sacrifices, and eerie traditions. But historical evidence tells a different, less sensational story about pagan practices in ancient Sweden.

The Foggy World of Ancient Scandinavian Religion

One big challenge when exploring ancient Scandinavian cults is the severe lack of detailed records. Few outsiders ventured into Viking Age Scandinavia to document customs, and when locals did write, they favored short rune inscriptions—not epic religious texts.

Runes themselves were primarily functional rather than magical or cultic. Not like the cryptic glowing runes you imagine in fantasy novels! Instead, they mostly served as brief labels or memorials. So, the rich mythology and rituals we know mostly come from far later texts or second-hand reports. This means there’s some guesswork involved, and stories often blend fact with legend.

Human Sacrifices: Fact or Fiction?

Human sacrifice is a headline-grabbing topic. Were people really sacrificed in pagan Sweden? Yes, but context matters.

- Ancient Norse stories—written down centuries after the Viking Age ended—do mention human sacrifices. For example, King Domaldi supposedly sacrificed himself to appease famine spirits. Odin himself, in the poetic myth Hávamál, famously sacrifices himself to gain wisdom.

- Accounts from outside Scandinavia, such as Adam of Bremen in the late 11th century, describe pagan sacrifices at the temple in Uppsala, Sweden, where humans and animals were offered during festivals. His descriptions are dramatic, but Adam, a Christian cleric, may have exaggerated to paint pagans in a worse light.

- Arab traveler Ibn Fadlan, meeting Vikings on the Volga River, gave an eyewitness account of a ritual human sacrifice of a slave woman during a leader’s funeral. This is one of the clearest firsthand reports.

- Archaeology lends support, too. The famous Elk Man grave in Birka, Sweden, shows high-status Viking burial with two decapitated bodies placed haphazardly—likely sacrifices connected to the funeral.

So, while sacrifices happened, they were rarely as frequent or theatrical as modern horror shows (or even movies like Midsommar) depict. Sacrifices usually served religious or funerary purposes, often limited to elite individuals or key ritual occasions.

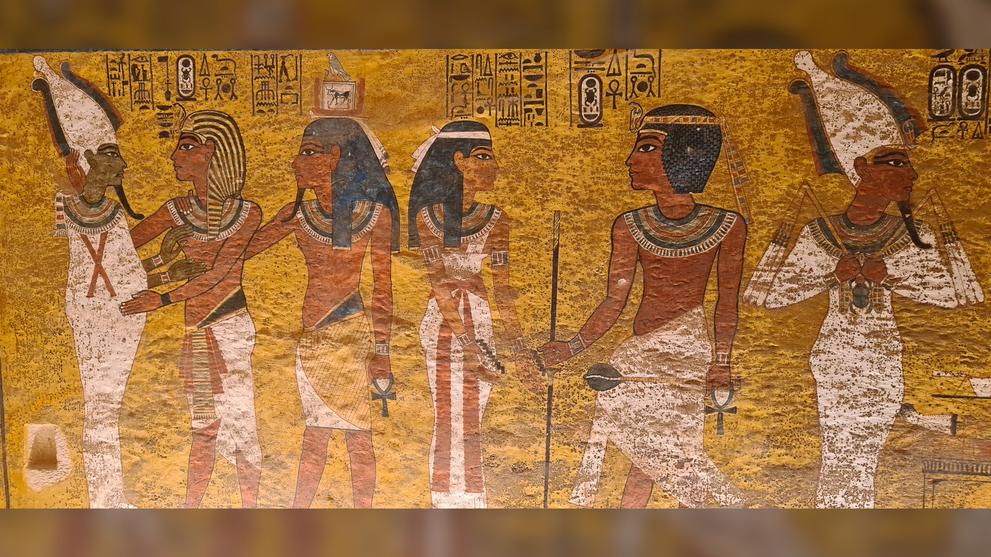

Water Rituals Go Way Back

The placement of sacrifices—human, animal, or weapons—in lakes and bogs is a well-known practice stretching back to the Stone Age and Bronze Age. Far from being rare, it was a consistent way to honor gods or spirits by returning offerings to water.

Some famous examples include:

- Tollund Man in Denmark, naturally mummified in a bog and thought to have been sacrificed around 300 BCE.

- Elling Woman found nearby with similar fate and dating.

- The Wild Strawberry Girl in Sweden, a teenage girl found in a bog, legs apparently bound, and deposited in what was then a shallow lake, likely as a sacrifice.

Such findings paint sacrifices not as bizarre oddities but woven into the fabric of religious life.

Ättestupa: Cliff Suicides That Never Really Happened

One especially eerie idea picked up by folklore and films is the ättestupa, supposedly cliffs where elderly Scandinavians committed suicide to avoid burdening their families. Sounds like a grim final chapter, right? But historians today dismiss this as myth.

This idea stems from a late saga—the Saga of Gautrek—which contains exaggerated, unrealistic tales. It wasn’t part of authentic ancient practice but grew through retellings and was later slotted into Swedish folklore. No archaeological or historical evidence supports real ättestupa.

The End of Pagan Sacrifices

Pagan practices, including sacrifices, faded as Christianity spread through Scandinavia, especially in Sweden by the 12th century. Kings crowned Christian put enormous pressure on traditional customs.

A vivid anecdote comes from the story of Blot-Sven, a pagan king who challenged the Christian King Inge by insisting on performing blóts (sacrificial rituals). Blot-Sven’s resistance didn’t last long, marking the twilight of pagan ritual sacrifice in Sweden.

So, Were There Cults Like in Midsommar?

In essence, ancient Sweden had pagan religious groups that practiced ritual sacrifices and seasonal rites, but not cults resembling the sinister, cult-like commune in Midsommar. The film’s eerie rituals—like gruesome human sacrifices conducted in broad daylight, complete with creepy dances and collective madness—are fictional dramatizations for entertainment rather than actual history.

In reality, pagan worship was decentralized, culturally diverse, and entwined with everyday life. Sacrifices happened but were symbolic, ritualistic, or funerary rather than frequent mass events. There’s no evidence of sinister “cults” controlling villages or demanding strange blood rites as a matter of course.

What Can We Learn from These Ancient Practices?

Understanding these older rituals helps us see how ancient peoples made sense of their world. Sacrifices, whether of animals or humans, often aimed to secure prosperity, favorable harvests, or protection from harm.

The archaeological record, combined with sagas and outsider accounts, cautiously stitches together a world where gods were respected through complex ceremonies—not the terror-filled cult gatherings some imagine from horror movies.

Moreover, the line between religious practice and myth is blurry. Our sources come with biases—Christian clerics disliked paganism and might exaggerate; later storytellers loved drama. That means sorting truth from fiction is tricky.

Final Thoughts: The Real Ancient Sweden Was More Complex

So if you’re wondering whether you’ll stumble upon a sunny Swedish village with a creepy floral cult demanding strange rituals, the answer is a firm no. Ancient Sweden’s religious life was nuanced, deeply spiritual, and often mysterious—but not a Midsommar-style horror show.

Instead, think of ancient Sweden as a land where water and nature ceremonies mingled with gods’ worship, sacrifices marked life’s critical points, and stories told enduring myths of heroes and deities—without the terrifying guessing games or daylight human sacrifices.

Next time you watch Midsommar, enjoy the artistry and story but remember the real history is fascinating and intricate in its own right, minus the wild cult theatrics.