Medieval feudal lords could not freely sell or trade the rights to their land in the modern sense, as fiefs were complex social and political instruments rather than mere property. However, selling or exchanging fiefs did occur under specific circumstances, though it was complicated and limited by feudal customs.

Fiefs represented more than land ownership. They included rights to collect taxes, exercise judicial powers, and wield regional political influence. These rights were tied to a social relationship between vassals and their lords, embedding landownership within a web of hierarchical obligations and loyalties.

Medieval lords rarely wanted to give up a fief. Even distant holdings served as bases of influence and power beyond direct control. Preserving these holdings reinforced a lord’s status and expanded his network of followers. Selling a fief risked deteriorating relations with one’s own lord, who was often a patron or protector, key to the vassal’s political and career advancement.

Despite these constraints, a market for fiefs existed in some regions like the County of Champagne around 1130-1150. Lords sometimes sold or exchanged fiefs to raise funds. Common reasons included financing Crusades or providing dowries. These transactions were pragmatic responses to immediate financial needs but remained exceptions rather than the norm.

The social nature of fiefs meant that transfers could not be simple sales as seen in modern property markets. Instead, they required approval and acknowledgment within the social hierarchy. Alienating a fief without consent risked conflict and loss of honor or support.

In summary:

- Fiefs were tied to social and political roles, not just land ownership.

- Medieval lords rarely sold fiefs due to social obligations and influence preservation.

- Sales or exchanges happened occasionally, often to fund Crusades or dowries.

- The transfer of fiefs depended on hierarchical consent and was not freely done.

Could Medieval Feudal Lords Freely Sell or Trade the Rights to Their Land?

Short answer: Not exactly. Medieval feudal lords couldn’t just put their lands on a medieval version of eBay and expect a quick sale. The rights to land during medieval times—wrapped in complex social, legal, and political relationships—were far from ordinary property transactions as we understand them today.

Let’s dive deeper to unravel this complicated story of medieval land rights, sales, and trades.

The Landscape of Medieval Feudalism: A Moving Target

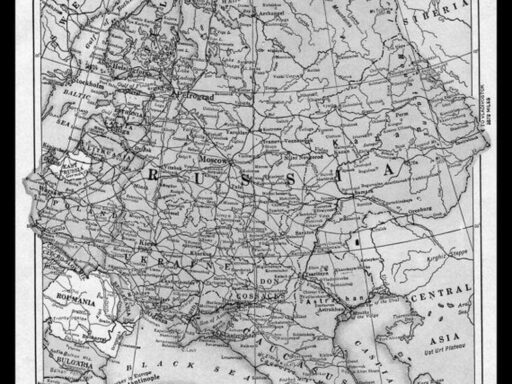

First off, talking about “medieval feudalism” is like trying to describe all flavors of ice cream as just “sweet.” The medieval era spans roughly a thousand years and covers vast territories from the coast of the Atlantic all the way to the Urals. Sounds like a lot to digest, right?

Even the meaning of words like ‘vassal’ and ‘fief’ shifted over time and among regions. What one lord understood as a fief might differ from the land-holding system operated by another noble in a different kingdom or century. So, before asking whether those feudal lords could sell the land, we need to understand what exactly they owned.

Ownership or Social Contract? The Confusing Nature of a Fief

Unlike modern property, a fief was more than just dirt and grass. It was a bundle of rights—a mixed bag of land rights, judicial authority, tax collection, and social status. Simply owning a piece of land was just a part of it.

At its core, holding a fief was a social relation. It was a hierarchy inked by loyalty and obligation between a lord and his vassal. The land symbolized this relationship rather than just a tradable asset. So, the question “Can I sell this land?” becomes more complicated than “Is the land mine to sell?”

The King’s Not Always the Landlord

You might imagine a king sitting on a throne, owning all the land and handing parcels out like gifts. But historians now agree that this is a bit of a myth. Kings never truly had absolute ownership of all land in their realms.

Many properties existed as private landholding, outside direct royal authority. This diversity meant that some lands were held as fiefs (under complex feudal duties), while others were held outright as “allodial” properties—lands owned completely and freely by an individual or family.

Allodial Property Versus Fiefs: A Distinction with a Blur

Allodial lands were fully owned with no superior lord to answer to. Fiefs, on the other hand, typically came with obligations, including military service and allegiance.

But even this distinction wasn’t always clear-cut. Some nobles might hold allodial land with the same power as a fief, or vice versa. In some cases, a fief was a nobleman’s term for their land, not necessarily a strictly feudal holding.

The Problem with Selling a Fief

Can a medieval lord sell his fief? Well, not simply or freely. The land was deeply tied up in obligations and relationships. Selling a fief might disrupt a lord’s influence and relationships with vassals and overlords.

For example, if a lord proposed to sell a fief far from his main base of power, he risked losing regional influence. Loyalty ran deep. Alienating a fief could mean alienating your lord or your followers—a political and social no-no.

Did Lords Ever Sell Their Land? Evidence Says Yes, But It’s Complicated

Despite all the hurdles and risks, nobles did sometimes sell or trade fiefs. How often? Rarely, but notably enough. For instance, Theodore Evergates, in his thorough exploration of the County of Champagne (1100-1300), dedicates a whole section to ‘The Market in Fiefs.’

Between roughly 1130 and 1150, a form of market for fiefs emerged in this region. Why? Mainly to raise funds! Crusades, dowries, wars, and other expensive endeavors forced nobles to raise cash. Selling a fief became a financial tactic, not a casual weekend listing.

What It All Means for Medieval Land Rights Today

The idea of freely buying and selling land, like flipping houses or trading NFTs today, just didn’t translate well to the realities of feudal Europe.

- Feudal land rights combined property with social and political ties.

- Kings didn’t always control all land; private landholdings existed alongside feudal ones.

- Nobles risked their status and influence by selling fiefs.

- Only under special circumstances—like funding a Crusade—would selling fiefs become more common.

So, if you’re picturing a medieval lord casually auctioning his castle or patch of farmland, think again. For lords, land was power, prestige, and political currency—not something tossed around like a simple commodity.

Practical Tips for Modern Historians and Enthusiasts

If you’re investigating medieval land ownership, remember:

- Consider the era and region: Feudalism was not uniform; laws and customs varied.

- Understand the social ties: Land was part of a broader political network.

- Look for evidence of sales: Documents like charters may reveal rare sales.

- Beware of modern assumptions: Don’t assume medieval rights worked like modern property laws.

Final Thought

Could medieval feudal lords freely sell or trade the rights to their land? Not quite. Their rights were tangled with obligations, loyalties, and social hierarchies that made land more than just a private possession. When they did engage in sales or trades, it was a strategic move often linked to financial needs or political maneuvering.

So next time you watch a medieval drama and see a lord just “selling the land,” remember the real story is far murkier—and infinitely more interesting.