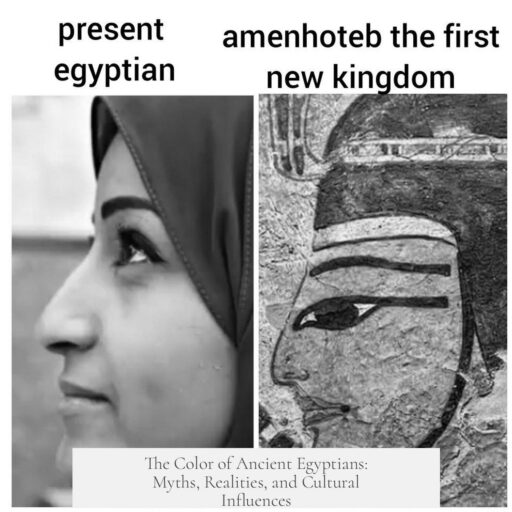

Ancient Egyptians exhibited a range of skin colors reflecting geographic diversity and complex cultural influences. Their depiction in art favors ideology, not literal representation.

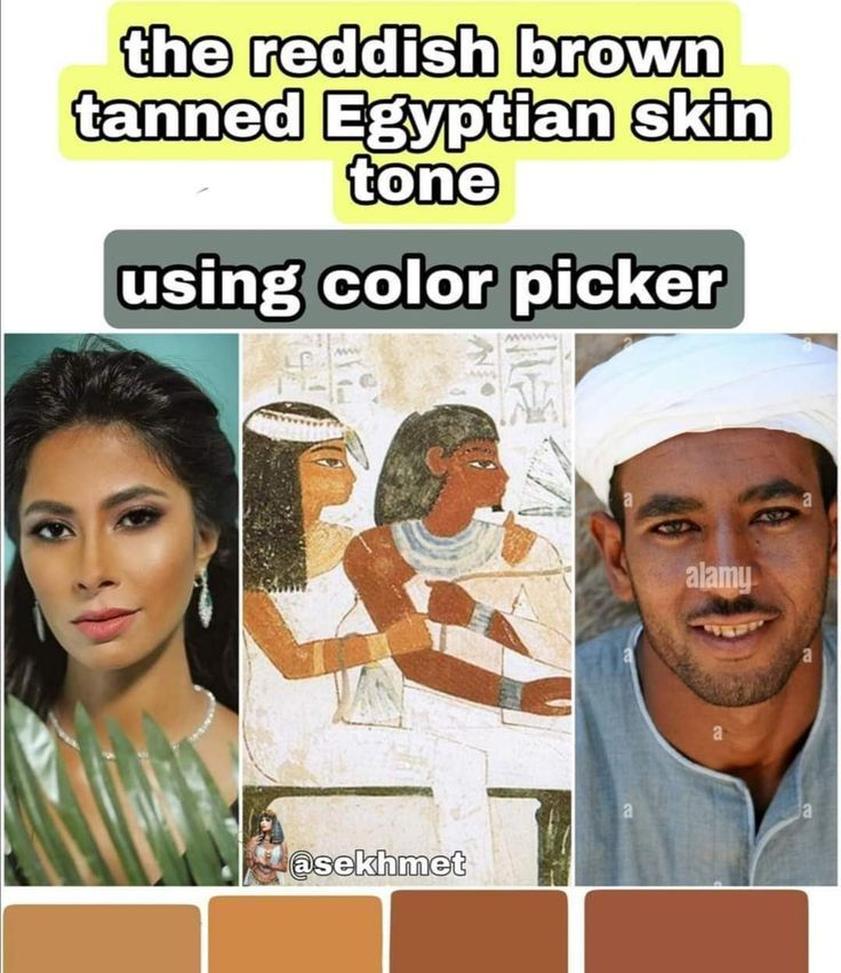

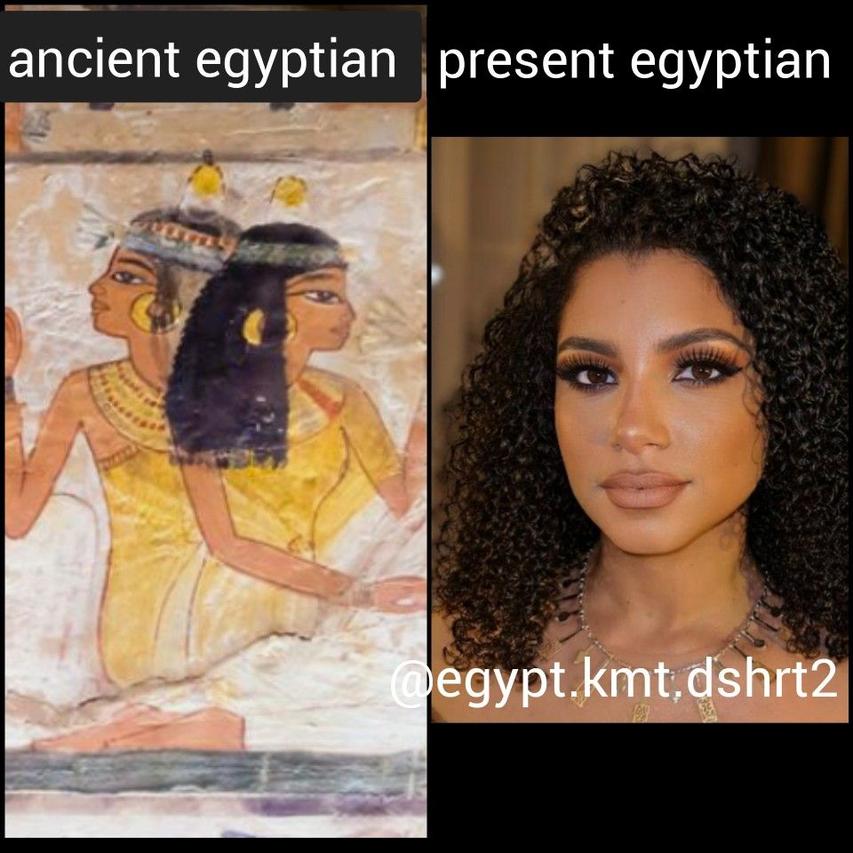

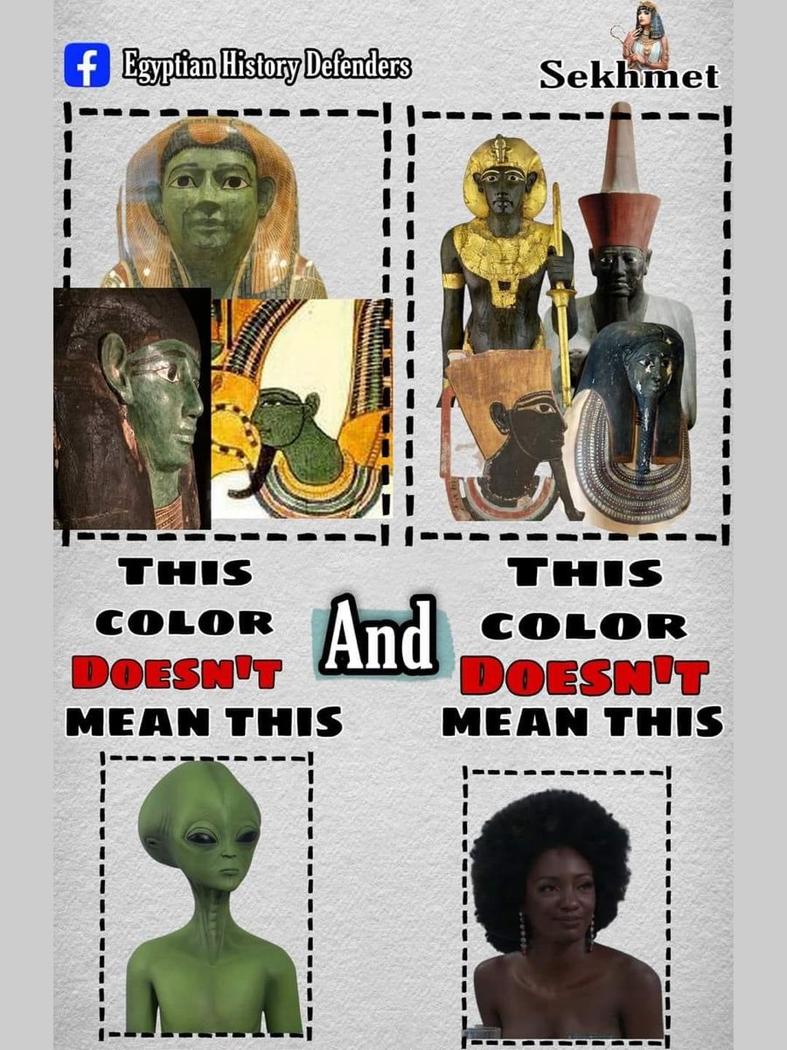

Egyptian art consistently shows men with reddish-brown skin and women with pale yellow or white skin. For instance, statues from the 4th Dynasty, like those of Prince Rahotep and his wife Nefret, illustrate this color distinction. These artistic choices aimed to symbolize gender roles or social status rather than provide accurate skin tones. Additionally, Egyptians portrayed neighboring groups with exaggerated skin colors—Libyans as very white, Semites lighter-skinned, and Nubians very dark—underscoring symbolic purposes over realism.

Skin color likely spanned a spectrum. Northern Egyptians featured somewhat lighter skin due to intermarriage with Levantine populations; southern Egyptians likely had darker skin influenced by Nubian neighbors. Ancient Egypt’s position as a crossroads attracted many ethnic groups—Cypriots, Canaanites, Aegeans, Nubians, and others—shaping a cosmopolitan and diverse society. Egyptians today primarily resemble the Mediterranean and Levantine peoples, exhibiting olive to medium-tan skin tones. Genetic studies confirm that modern Egyptians largely descend from ancient ancestors, with some increase of sub-Saharan African admixture after the Arab conquest.

The ruling elites changed over time, reflecting Egypt’s history of conquest. Nubian kings once governed Egypt, adding African traits to the royal line. The Hyksos, thought to be Semitic, ruled parts of Egypt temporarily. Later, Greek Ptolemaic rulers, of Macedonian descent, brought European traits. Cleopatra VII, the famous queen, descended from this Greek lineage and probably resembled modern Greeks more than indigenous Egyptians. Nonetheless, Ptolemies often married native Egyptian women, mixing genealogies.

Daily life in ancient Egypt influenced skin shades through sun exposure. Farmers working outdoors appear darker than the lighter-toned elite, who mostly stayed indoors. This tanning effect further complicated skin color assessments. Archaeological and artistic evidence reveal thick, dark hair was common, but overall facial features and skin tones varied widely.

Attempts to classify ancient Egyptians by modern racial categories prove unreliable. Ancient societies did not view race as contemporary cultures do. There’s no single “African race,” as Africa holds greater genetic diversity than other continents combined. Many distortions arise from racial chauvinism or politically motivated historic revisionism, such as Afrocentric claims that oversimplify or exaggerate native black African identity. Similarly, European scholars historically portrayed Egyptians as white to serve racist ideologies.

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Artistic portrayal | Men appear reddish-brown; women pale yellow/white; symbolic, not literal |

| Geographic variation | North Egypt lighter skin; South Egypt darker skin due to Nubian influence |

| Cosmopolitan makeup | Diverse mix including Cypriots, Canaanites, Greeks, Nubians, and others |

| Ruling classes | Varied ancestry including Nubian, Semitic, Greek Macedonian |

| Modern genetics | Modern Egyptians mostly descend from ancient Egyptians; some increased sub-Saharan admixture |

| Sun exposure effect | Outdoor workers darker; indoor elites lighter; skin tone affected by environment |

Ancient Egyptians probably resembled modern North Africans with Mediterranean traits. They were neither uniformly black nor white but exhibited medium-tan complexions consistent with regional populations around the Mediterranean basin. The Egyptian self-view ranked their skin tone as lighter than Nubians but darker than Hebrews and Greeks, reaffirming a distinct identity shaped by geography and history.

- Egyptian art uses skin color symbolically, not realistically.

- Skin tones varied due to geography and intermarriage with neighboring peoples.

- Society was ethnically diverse owing to trade, conquest, and migration.

- Ruling classes included Nubian, Semitic, and Macedonian Greek lineages.

- Modern Egyptians genetically mirror their ancient ancestors with some changes.

- Sun exposure influenced apparent skin color between social groups.

- Modern racial categories do not apply to ancient populations effectively.

The Color of Ancient Egyptians: Myth, Reality, and Everything In Between

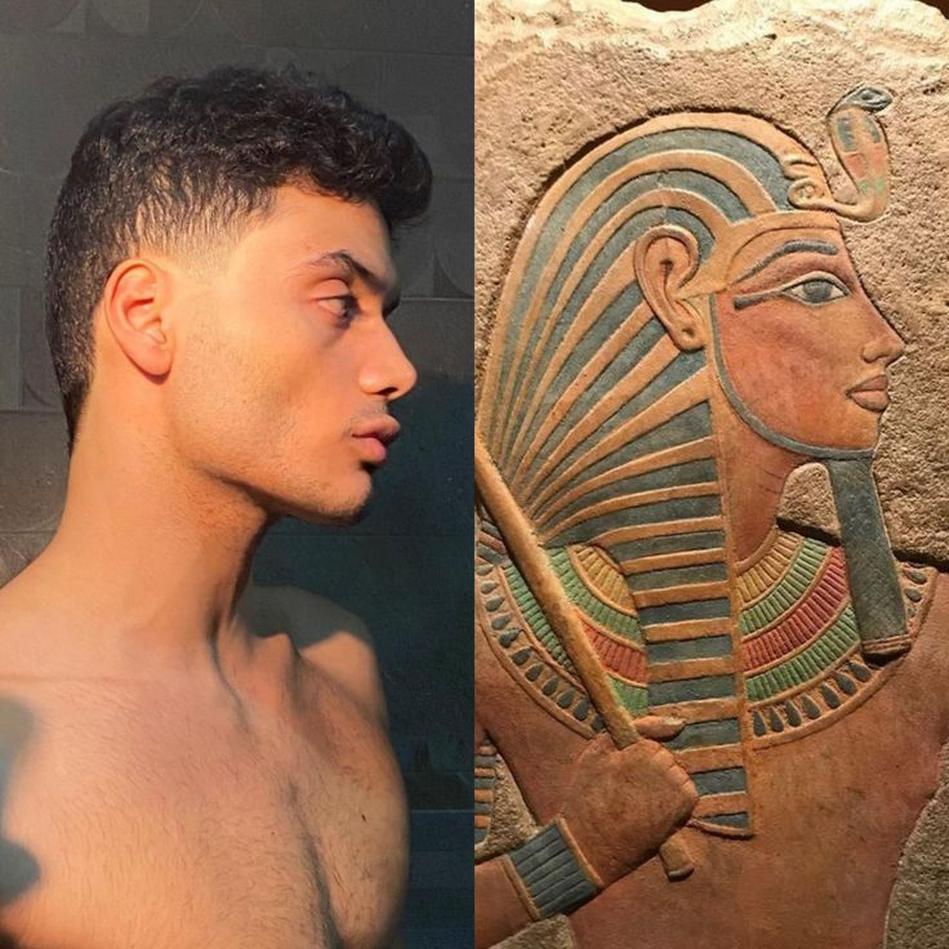

If you ask what the color of ancient Egyptians really was, the succinct answer is this: their skin color was as varied as the Nile itself, reflecting a complex blend of geography, culture, and art — not just a simple shade you can scribble on a palette. Forget stereotypes and modern racial boxes; ancient Egyptian color was a tapestry, woven from real human diversity and layered with symbolic meanings.

Stretch your imagination beyond dusty sculptures and hieroglyphs. The ancient Egyptians were people who lived, worked, and ruled along the banks of the Nile. Their skin color was influenced by sun, ancestry, and yes, artistic choices that served a purpose beyond realism.

Skin Color as Ideology in Egyptian Art: The Art of Idealization

Here’s a juicy factoid to chew on: the way Egyptians painted themselves in tombs and temples often tells us more about their culture’s values than about their actual skin tone. Artistic depictions are less like photographs and more like a cultural Instagram filter.

Take the famous 4th Dynasty statues of Prince Rahotep and his wife Nefret—he sports reddish-brown skin, she appears white or pale yellow. This contrast wasn’t about biology but symbolism. Men got more reddish-brown paint, representing outdoor labor under the sun or perhaps masculine vitality. Women were often painted lighter to convey a distinction between genders, roles, or ideal beauty.

“Egyptians often depicted Libyans as very white, Semites with a lighter skin, Egyptian men as red, women as yellow, and Nubians as dark brown. It’s stylized exaggeration, not a census.”

Artists deliberately used pigments like red ochre or yellow to mark social and ethnic differences. Peasants, for example, tended to be painted darker simply because there was limited pigment and because it visually separated them from elites. This wasn’t a color photo from 3000 years ago; it was an ideological declaration.

A Spectrum of Skin: Geography and Genetics in Ancient Egypt

Side-stepping art, what about the real flesh-and-blood people? Ancient Egypt stretched over 1,000 miles along the Nile, from the Mediterranean to Nubia, with diverse climates and neighbors.

The skin tone of Egyptians likely formed a gradient: lighter in the north due to interactions with Levantine populations, and darker down south with intermarriage among Nubians. Picture it as a smooth range rather than a single shade on a crayon box.

This geographic variability means the simplistic “all Egyptians looked like X or Y” idea falls flat. City-dwellers and traders from regions including Cyprus, the Aegean, and the Levant created a melting pot where Mediterranean and African ancestries met.

Cosmopolitan Egypt: Where Colors and Cultures Mixed

Imagine ancient Egypt as a bustling port café on the Mediterranean, with traders, scribes, soldiers, and peasants from myriad ethnicities. From the Middle Kingdom onward, Egypt was rarely isolated.

- Cypriots, Canaanites, Nubians, Aegeans, and others mingled within Egyptian society.

- Facial features varied—curly, thick, or even shaved heads were common.

- Pharaohs didn’t always come from pure Egyptian bloodlines; they often had mixed heritage influenced by rulers like Nubians and Greeks.

This diversity gave Egypt a unique “North African Mediterranean” complexion and culture, far from a monochrome narrative.

Cleopatra and the Ptolemaic Dynasty: A Different Hue

Let’s talk about Cleopatra—the queen of many debates. Contrary to some modern speculations, Cleopatra wasn’t African in the way some Afrocentric narratives claim.

She descended from the Greek Macedonians of the Ptolemaic dynasty, a line stemming from Alexander the Great’s generals. That’s basically Mediterranean-European heritage. While the Ptolemies often married their siblings, keeping a distinct Greek bloodline, they ruled over a diverse population.

Was Cleopatra white in the 21st-century sense? Probably yes—like a modern Greek. But she was ruling a multicultural land, and likely married into or at least interacted with Egyptians of varying background as part of political legitimacy.

Modern Egyptians: DNA Ties to the Past

Fast forward to today. DNA testing on mummies and living Egyptians reveals something astonishing: modern Egyptians share over 90% of their genetic ancestry with ancient Egyptians.

Surprisingly, modern Egyptians have a bit more sub-Saharan African genetic influence, likely due to population movements in later centuries. Still, the Egyptians you meet in Cairo or Luxor stand as living connections to their ancestors.

This genetic continuity supports the idea that skin color and features among Egyptians have long represented a range, rather than a static image.

Rulers from Elsewhere: A Palette of Leaders

Ancient Egypt’s rulers came in a variety of “colors,” literally and figuratively. The Hyksos, a Semitic group, ruled parts of Egypt temporarily. Nubian kings, with darker skin, governed Upper Egypt and even the entire kingdom at times. The Greeks and Romans entered the mix later on.

These shifts brought diverse genetics into the elite strata, but most common Egyptians remained rooted in their agro-North African heritage.

What Did Egyptians Themselves Say About Their Color?

It’s not just us guessing here. Ancient Egyptians described themselves as “lighter than the Nubians but darker than the Hebrews and Greeks.” That’s a pretty specific self-assessment that travels beyond black-and-white classifications.

Think about modern Mediterranean populations—Italians, Sicilians, Spaniards—they range in skin tone, often described as “olive.” Ancient Egyptians fit comfortably into this same regional tone.

This challenges any simplistic narrative: they were not “white” as in Northern European pale, but neither were they dark-skinned in an all-or-nothing way.

Environmental Effects: Tanning and Lifestyle

The desert sun left its mark on Egyptians just the same way it does today. Peasants, farmers, and outdoor workers naturally had darker, tanned skin. Some royals and scribes, who spent more time indoors or shielded under fine linens, looked lighter.

This means that any snapshot of skin tones must consider both genetic heritage and time spent outdoors.

The Afrocentric Debate: Race, Politics, and History

This topic opens a can of worms. Many groups want to claim ancient Egypt’s legacy, sometimes stretching facts to fit narratives. Afrocentric movements highlight African roots, while some misinterpretations stretch that to say all Egyptians were black African in the modern sense.

Both extremes often miss that:

- Ancient Egypt was a mix of many peoples.

- Modern racial classifications don’t map neatly onto ancient societies.

- Eurocentric whitewashing of Egyptian history was driven by racist agendas.

The truth is complex, and we must avoid projecting modern racial ideas onto ancient worlds.

Modern Race Concepts and Why They Don’t Apply

Race, as we understand it today, is a relatively modern invention. It blossomed during the Transatlantic slave trade when Europeans categorized people to justify brutality.

Africa, including Egypt, holds immense genetic diversity, far more than Europe or Asia combined. This makes any attempt to label ancient Egyptians “black,” “white,” or “brown” insufficient and misleading.

Applying modern categories to ancient Egyptians is like trying to fit a sprawling Renaissance tapestry into a selfie crop—important details are lost.

So, What’s the Bottom Line?

Ancient Egyptians looked like a broad spectrum of Mediterranean and North African peoples. They varied by geography, occupation, lineage, and even their roles in society. Their representations in art were often symbolic, not literal, using color to convey meaning rather than document reality.

Modern Egyptians carry much of their ancestors’ DNA, supporting the idea of continuity with diversity. Cleopatra’s image as a “black queen” is mostly a myth; she was of Hellenic descent. The ruling classes varied in ethnicity more than the general populace, which stayed primarily rooted in North African genetics.

In short, Egyptians were neither one race nor color — they were the complex, vibrant people of a cosmopolitan civilization, living and adapting along the life-giving Nile. Their color reflects this richness—both biologically and artistically.

Need a Quick Recap?

- Egyptian art uses color symbolically, not literally.

- Skin color likely ranged from light to darker brown, with geographic gradients.

- Egypt was a diverse, cosmopolitan society with many ethnicities mingling.

- Cleopatra was Greek Macedonian, not representative of ancient Egyptians overall.

- Modern Egyptians share most genes with their ancient ancestors.

- Rulers came from varied backgrounds, including Nubians and Greeks.

- Environmental factors like sun exposure affected skin tone.

- Modern racial concepts do not neatly fit ancient realities.

- Debates on Egyptian skin color often reveal more about contemporary concerns than ancient facts.

Curious to Dig Deeper?

To further explore this vibrant mix of history, you might enjoy viewing the Prince Rahotep and Nefret statues, a prime example of how ancient art used color. Or dive into DNA studies published by Nature that show the genetic links between ancient and modern Egyptians.

If you’re feeling brave, consider how culture, politics, and identity shape interpretations of history. Ancient Egypt’s legacy is too magnificent and multi-colored to be boxed into a single tone.

So next time you see an image of an Egyptian Pharaoh, remember: the man behind the crown had a story — and a complexion — far richer than just “red, yellow, black, or white.”

After all, history, like art, loves a good palette.