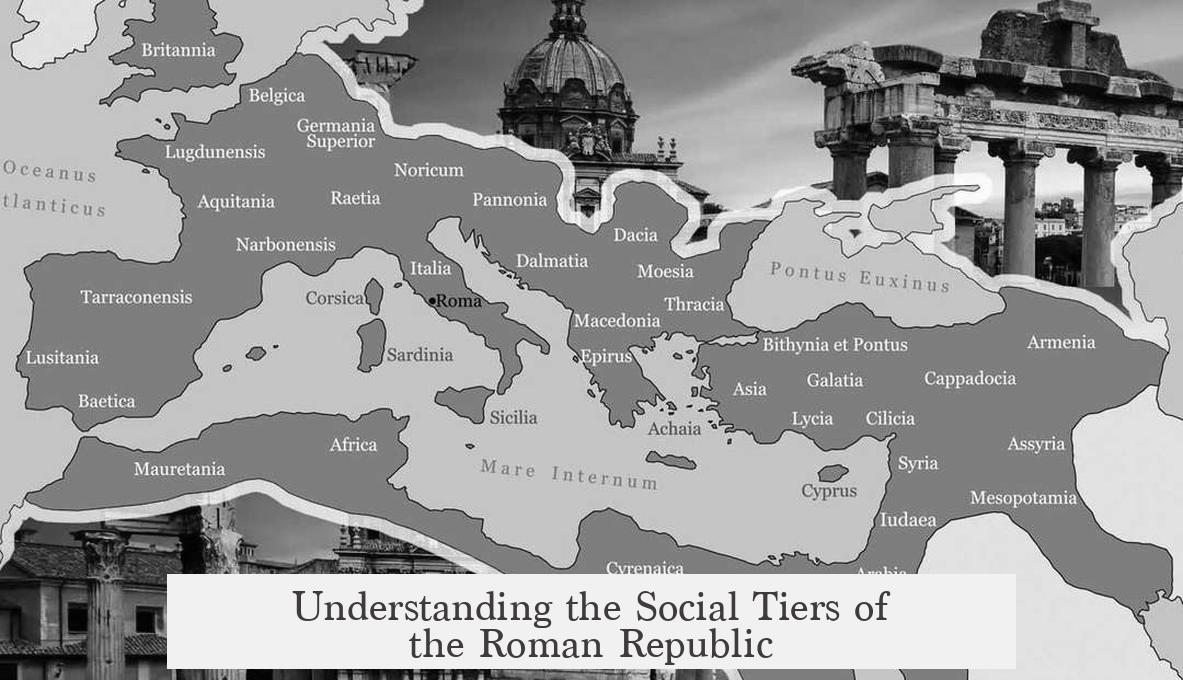

The Roman Republic’s social and political tiers form a complex hierarchy based on heritage, wealth, political office, and geography. By Caesar’s time, traditional divisions between patricians and plebeians lost much significance, while wealth and political offices largely defined status and influence.

Initially, Roman society was divided into patricians and plebeians. Patricians descended from Rome’s original senatorial families, while plebeians encompassed everyone else. This distinction was hereditary but did not imply nobility or poverty. By the late Republic, most influential families, generals, and consuls were plebeian. For instance, famous leaders like Crassus and Pompey were plebeians. Julius Caesar was a noteworthy exception as a patrician, though from a less prominent family. Some legal remnants, like barring patricians from becoming Tribunes of the Plebs, still existed but had little social impact.

At the top of the political and social ladder stood the Senate. Originally a council of 300 prominent nobles and former magistrates, the Senate grew to 600 or more under Caesar. It advised magistrates and assemblies on laws and foreign policy. Senators enjoyed substantial informal power despite limited formal authority. Entry required election to a magistracy, reflecting political achievement rather than birth alone.

Roman social class sharply reflected wealth, forming tiers used in voting and political rights. Just below senators were the Equestrians or Ordo Equester, wealthy landowners and businessmen who had evolved from Rome’s cavalry elite. Below them, five classes based on property qualification existed, ending with the capite censi or proletarii. These poorest citizens owned minimal property and contributed mainly their votes. Unlike plebeians, the proletarii represented the true poor class.

The comitia centuriata (Assembly of the Centuries) used these wealth-based classes for voting. Citizens were divided into centuries weighted by wealth. Smaller centuries of rich citizens carried more voting power than larger, poorer ones. Thus, the richer a voter, the greater their political influence.

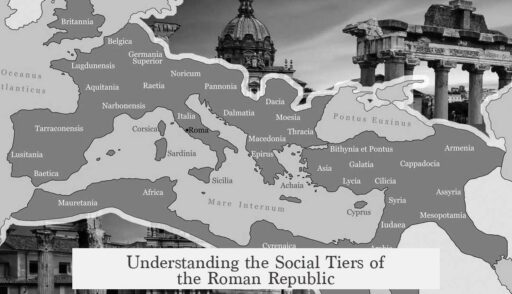

Another voting division was the Tribal Assembly, organized geographically. Citizens belonged to tribes based on residence. There were 35 tribes: four urban and 31 rural (rustic). Each tribe cast a single vote regardless of population size. Since many poor citizens lived in urban tribes, their influence diluted compared to rural representatives. Rural tribes included rich landowners who rarely traveled to vote but controlled political power through this system.

The Roman political career operated through the structured Cursus Honorum, a sequential ladder of elected offices. It started with entry-level roles and progressed to the highest positions. Offices were held typically for one year, with specific age requirements and duties:

- Military Tribunes: young men assisting generals in military affairs.

- Quaestors: officials in their 30s handling finances.

- Tribunes of the Plebs: legislators with veto power, reserved for plebeians.

- Aediles: organizers of public games and festivals.

- Praetors: judicial officials who could command armies.

- Consuls: chief magistrates and heads of state, usually men in early 40s.

- Censors: officials charging with conducting censuses and managing senate rolls.

After serving as praetor or consul, officials often governed provinces as proconsuls or propraetors with near-autonomous authority and command over military forces. Holding offices conferred prestige and influence beyond their term.

While elections existed, they favored the wealthy, leveraging voting systems like the comitia centuriata and tribal assemblies to maintain elite control. Senate membership often combined political success with social standing more than mere hereditary status. The blurred lines between aristocracy and commonalty reflected a dynamic society adapting to power shifts.

| Tier | Basis | Role and Influence |

|---|---|---|

| Patricians vs. Plebeians | Hereditary | Little political impact by Caesar’s era; some legal distinctions remain |

| Senate | Political Office & Status | Advisory role; highest prestige; former magistrates |

| Equestrians & Wealth Classes | Wealth | Economic elite; weighted voting power in assemblies |

| Tribal Assembly | Geography | Voting districts with disproportionate rural elite control |

| Cursus Honorum | Political Career Path | Structured ladder of offices granting increasing power |

- Patrician/plebeian divides fade in relevance by late Republic.

- The Senate holds elite advisory power, with many from non-patrician families.

- Wealth strongly determines voting weight and political influence.

- Geographical tribes skew political power toward rural elites.

- The Cursus Honorum defines the sequence of political offices essential for leadership roles.

What was the real difference between Patricians and Plebeians in the late Roman Republic?

By Caesar’s time, this distinction had lost much of its meaning. Patricians were descendants of Rome’s original senate, but most leading families and generals were Plebeians. Only a few laws still distinguished them.

How did wealth affect voting power in the Roman Republic?

Wealth determined your social class and voting influence in the Comitia Centuriata. Richer classes had fewer voters but more centuries, giving their votes greater weight compared to poorer classes with many voters.

Why did rural tribes have more political influence than urban tribes?

Each tribe had one vote, and there were 31 rural tribes but only 4 urban ones. Since the poor mainly lived in urban tribes and could not always travel to vote, the rural tribes, full of the elite, dominated tribal voting.

What roles did the Senate and elected magistrates have?

The Senate was a prestigious advisory council with little formal power. Magistrates like Consuls and Praetors held actual executive and judicial powers, elected for fixed terms and often moving on to govern provinces.

Can anyone become a senator or magistrate in Rome?

Theoretically, anyone elected as a magistrate could join the Senate. Although coming from a senatorial family helped, it was possible for wealthy Plebeians to rise through the political offices known as the Cursus Honorum.