The Life of Saint Issa, as presented by Nicholas Notovitch in the late 19th century, is widely discredited as a fabrication. It lacks credible evidence, contradicts historical and linguistic facts, and faces outright denial from Tibetan sources and expert scholars.

Notovitch claimed to discover ancient manuscripts at the Himis monastery describing Jesus (termed “Issa”) traveling to India and Tibet during his “lost years.” However, thorough investigations and scholarly scrutiny reveal serious doubts about the story’s authenticity.

First, Notovitch’s alleged journey and discovery contain multiple implausible details. According to him, monks at Himis had detailed knowledge of Saint Issa and allowed him to access ancient texts. Yet, no Tibetan scholar or historian corroborated the existence of Issa or such manuscripts over the subsequent century. In fact, prominent experts like Max Müller and J. Archibald Douglas directly questioned the monastery’s chief lama, who denied any knowledge of Issa, the manuscripts, or related teachings. Douglas’s report quotes the lama vehemently rejecting Notovitch’s claims as “lies” and stating no European visitor with a broken leg (Notovitch’s stated reason for stay) had appeared in recent years.

Notovitch invented a story that a leg injury detained him at the monastery, enabling his reading of the text. Tibetan hospital records from nearby Leh indicate he sought treatment for a toothache instead, undermining his injury story. This casts doubt on the account of his stay and research opportunity.

Notovitch’s description of the manuscript itself raises suspicion. He described two large bound volumes, resembling Western bindings unknown in traditional Tibetan cultures. Elisabeth Caspari, who visited the same monastery decades later, photographed an authentic Tibetan xylograph—far different from Notovitch’s description. The absence of the original manuscripts or any copies also weakens the credibility of his assertion.

The role of Notovitch’s interpreter further limits trust. His companion was a Kashmiri hunter likely fluent only in English and Urdu, not qualified to translate complex Tibetan religious texts. This discrepancy questions the accuracy and possibility of receiving genuine teachings through such a language barrier.

Within the text of the “Life of Saint Issa” itself, inconsistencies abound:

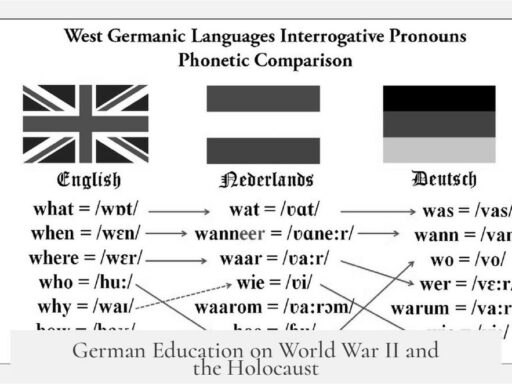

- The name “Issa” is an Arabic iteration of Jesus, improbable in Tibetan or Pali translations where different forms would appear.

- The name Pontius Pilate appears without linguistic corruption, a surprising detail given the distance and the expected transmission errors across cultures.

- The text’s format uses numbered verses, a convention that only appeared in Europe centuries after Jesus’ time, signaling a modern concoction rather than an ancient manuscript.

- Brahmans educating Jesus in the Vedas contradicts known socio-religious contexts of ancient India. Foreigners, especially Jewish ones, rarely received formal Vedic training.

- Jesus being an appointee of Buddha mixes timelines illogically, since Buddha lived roughly 500 years before Jesus.

- Terms like “pagans” are foreign to Buddhist terminology and show Christian European influence rather than authentic Tibetan or Indian perspectives.

- The claim that Jewish authorities refused to persecute Jesus runs counter to canonical and historical records and seems self-serving or drawn from Notovitch’s background.

These textual anomalies strongly indicate a fabrication shaped to fit 19th-century Western fantasies about Jesus’ exotic travels, merging Christian and Eastern religious motifs without historical foundation.

Historically, the Life of Saint Issa emerges from a lineage of similar claims. The French writer Louis Jacolliot advanced parallel ideas in 1869, proposing that Jesus and Krishna were identical. Later, François Laouenan invented supporting documentation. Notovitch’s 1894 book is part of this trend, but unlike Jacolliot and Laouenan, he claimed firsthand discovery, which after closer examination, proves tenuous and conflicting.

Notovitch himself led a complex life. Born into a Jewish family, he converted to Russian Orthodoxy and worked as a possible spy. After publishing his book, he faced arrest and exile in Siberia, possibly linked to his controversial claims. He disappeared from records after 1916, leaving a puzzling legacy overshadowed by academic skepticism.

Calls by respected scholars for verification evoked direct investigations. Max Müller’s correspondence and Douglas’ visit to Himis exposed the lack of evidence and Tibetan denial. The chief lama’s statements are unequivocal:

No European with injury visited in recent years. No manuscript named Life of Issa exists. Jesuss’ story is unknown except through foreign missionaries.

This straightforward rebuttal has never been substantially challenged. The original text has never materialized. No corroborating archaeological or manuscript evidence supports the narrative. Notovitch’s reliability remains highly questionable given these contradictions and deceptions.

Summarizing the key points:

- No independent verification of the Life of Saint Issa manuscripts exists.

- The Himis monastery and Tibetan monks deny all knowledge of Issa and the supposed texts.

- Internal inconsistencies and anachronisms in the narrative reveal a modern composition.

- Historical and cultural claims contradict established facts regarding timelines, language, and beliefs.

- The original source has never been produced, relying solely on Notovitch’s unsupported word.

- Scholars such as Max Müller and J. Archibald Douglas conclusively debunk it.

In sum, the Life of Saint Issa remains a curious episode in religious folklore but has no firm foundation in historical reality. It serves as an example of how 19th-century exoticism and romanticism about Jesus’ life inspired unfounded narratives. Readers should approach it critically and rely on corroborated scholarship about Jesus and historical Tibet.

Can anyone help me debunk the Life of Saint Issa?

The Life of Saint Issa, popularized by Nicholas Notovitch in 1894, is widely debunked by scholars as a fabricated tale without any credible evidence. This intriguing story claims that Jesus traveled to India and Tibet during his “lost years” and learned spiritual wisdom there. But does it hold up to scrutiny? Let’s dive into the twists, turns, and downright tall tales surrounding this curious manuscript.

Ever heard of the book La vie inconnue de Jesus Christ? That’s Notovitch’s 1894 publication, often referenced as the “Life of Saint Issa.” Before delving further, you should know the origin of this idea wasn’t born in a vacuum—it started with earlier, less scholarly musings.

A Brief Backstory: From Louis Jacolliot to Notovitch

The seed was planted in 1869 by French lawyer Louis Jacolliot, who boldly theorized Jesus and the Hindu god Krishna were one and the same. Not exactly the most scholarly statement, but it stirred curiosity. Then came François Laouenan, who in 1885 fabricated sources to inflate this narrative. Enter Nicholas Notovitch, a Russian adventurer, who claimed to have found primary Tibetan manuscripts at the Himis monastery chronicling Jesus’s sojourn in the region. Sounds exciting, right?

Notovitch was not your ordinary explorer. Born in 1858 into a Jewish family, he converted to Russian Orthodoxy and may have had spy duties. Around 1887, he toured India and Tibet. After his trip, he published his sensational book in Paris. Later, he was arrested and exiled to Siberia in 1895, with rumors linking the exile to the fallout from his publication—but these remain murky. Notovitch vanished from history after 1916, leaving behind just this controversial legacy.

Why Notovitch’s Claim Does Not Hold Water

Thorough examinations have cast deep doubts on the authenticity of the Life of Saint Issa. Let’s talk about some red flags.

Implausible Tales of Manuscript Discovery

- Monks’ “Knowledge” about Issa: Notovitch asserted that monks at Himis monastery knew Saint Issa well. However, no other Tibetan scholar has found any mention of Issa in over a century of intense research on Tibetan history and religion. That’s a huge silent alarm.

- The “Injury” Cover Story: Notovitch claimed he stayed at the monastery after breaking his leg. But hospital records show he only suffered a toothache during his stay. A small detail, but it undermines his credibility.

- The Manuscript’s Suspicious Format: He described the manuscript as large bound volumes—odd, since Tibetan texts traditionally come as loose wooden xylographs, not Western-style books, which didn’t even exist when Jesus lived.

- Elisabeth Caspari’s Contradiction (1939): Another visitor found typical Tibetan manuscripts, snapping photos that sharply contrasted with Notovitch’s description.

- Interpreter Mismatch: His interpreter was a Kashmiri hunter who likely only spoke Urdu and English, making it improbable that he correctly translated complex religious discussions during Notovitch’s stay.

- No Original Text: To this day, no original manuscript or transcript has surfaced—Notovitch’s account is all we have. And that’s shaky ground.

Confrontations with Scholars and Monastery Officials

Notovitch’s claims attracted attention from respected orientologists. The famous Max Müller asked the chief lama at Himis directly. Then British scholar J. Archibald Douglas visited the monastery in person.

“Lies, lies, lies, nothing but lies!” said the chief lama when confronted. He firmly stated:

- No injured European had stayed at Himis in over 15 years;

- No “Life of Issa” manuscript existed, was shown, or translated;

- “Issa” was unknown to the monks except by hearsay from Europeans or missionaries;

- No references to Egyptian, Assyrian, or Israelite religions in their records.

Douglas concluded that Notovitch was unlikely to be welcomed back to the monastery and probably barred from entry. Quite a damning verdict.

Internal Inconsistencies within the Text

The text itself doesn’t quite add up either.

- The name “Issa” is Arabic for Jesus, making it improbable for that exact name to appear in Tibetan or Pali translations directly.

- Remarkably, the name Pontius Pilate appears perfectly preserved—too perfect, given the centuries and language shifts involved.

- The text is divided into numbered verses—a style European scribes introduced centuries after Jesus’s time.

- The narrative claims Brahmans educated Jesus in the Vedas, which is highly improbable. Brahmans, known for exclusivity, teaching a foreign visitor? Not likely.

- Jesus supposedly appointed by Buddha, who lived centuries earlier. That timeline defies logic.

- Use of terms like “pagans” is culturally and historically out-of-place in Buddhist contexts.

- The story states Jewish authorities refused to persecute Jesus, contrary to historical and biblical accounts.

These inconsistencies suggest a text assembled more from imagination than from authentic ancient sources.

So, Why Does the Life of Saint Issa Persist?

Humans love mysteries about lost years of famous figures. The idea of Jesus wandering through the mystic East tickles our fascination with cross-cultural spiritual wisdom and secret teachings. Notovitch’s story plays right into those cravings.

But without evidence, without credible witnesses, and amid clear contradictions, it becomes clear this tale belongs in the fiction section. For scholars, it’s a textbook case of fabrication; for seekers, a cautionary tale about the importance of fact-checking.

Where to Learn More and See the Debunks

For those who want to dig deeper, start with:

- Klafkowski P.’s study From Russia with love dives into the myth and historical context. Read it here.

- B. N. Rice’s The Apocryphal Tale of Jesus’ Journey to India offers detailed analysis with modern scholarship. Find it here.

- Original debunks by Max Müller and J. Archibald Douglas are available on tertullian.org.

- Louis H. Fader’s book The Issa Tale That Will Not Die is a comprehensive biographical attack on Notovitch’s claims and worth seeking out.

Final Thoughts: A Lesson in Skepticism

The story of Saint Issa is a fascinating chapter in the history of religious myth-making. It reminds us: extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. When faced with miraculous assertions—like Jesus spending his “lost years” studying Buddhism in Tibet—pause, probe, and demand credible proof.

In this case, not only did the physical evidence never appear, but eyewitness testimony from credible sources directly opposed Notovitch’s claims. Linguistic impossible timelines, historical inaccuracies, and cultural mismatches abound.

So, next time you hear about the Life of Saint Issa, remember: it’s a neatly wrapped package of fantasy masquerading as fact. You owe it to yourself to debunk before you believe.

Ready to explore the myths behind other spiritual legends? Keep your critical thinking cap handy—it’s your best tool in the quest for truth.