Before the American Revolution, the present-day United States was primarily known as the “American colonies” or “North American colonies” under British rule. These terms referred specifically to the British settlements along the Atlantic coast that later formed the United States.

In the 18th century, British subjects and official documents often called these areas the “American colonies.” For example, documents from 1766 use phrases such as The Justice and Necessity of Taxing the American Colonies Demonstrated and The Grievances of the American Colonies Candidly Examined. These references show the common usage of “American colonies” in English discourse.

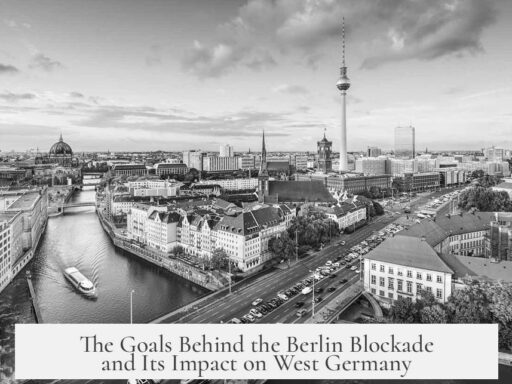

The term “American colonies” distinguished this group of colonies from other British holdings in North America and the Caribbean. Britain controlled large territories on the continent beyond these colonies including Hudson’s Bay, Labrador, Newfoundland, Canada (then called Quebec), Nova Scotia, and East and West Florida. These were separate and often governed separately from the coastal colonies that later became the United States.

It is important to note that the phrase “Thirteen Colonies” was not used during this period. This descriptor emerged only after the revolution to collectively name the colonies that rebelled. No verified evidence shows the term “Thirteen Colonies” in use before American independence. Instead, the plural “colonies” or the geographic modifier “American” clearly identified this group of British settlements.

| Term Used | Meaning | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|

| American Colonies / North American Colonies | British colonies along North America’s Atlantic coast forming future US | 1766 publications, legal documents |

| Other British Colonies | Separately governed British territories in continental & Caribbean America | Hudson’s Bay, Quebec (Canada), Nova Scotia, Florida, Caribbean islands |

| Thirteen Colonies | Later term for the colonies that formed the US, post-Revolution | Not used before 1776 |

In summary, before the American Revolution, the future US was called the “American colonies” within the British Empire. This distinguished the coastal settlements from other British possessions in America and the Caribbean. The unifying term “Thirteen Colonies” only appeared after independence.

- “American colonies” was the common contemporary term

- It referred to British-controlled settlements on the continent’s eastern seaboard

- Other British territories in North America and the Caribbean were distinct

- “Thirteen Colonies” emerged post-Revolution as a collective name

Before the American Revolution, what was the present-day US called?

Before the American Revolution, the present-day United States was mostly known as the “American colonies” or the “North American colonies.” It was a patchwork of British colonies, distinct from other British holdings in the Americas, and the now-famous “Thirteen Colonies” term only appeared after independence was won. Sounds simple, right? Yet, the story behind these names reveals a lot about identity, governance, and the path to independence.

Imagine living in the mid-1700s. You’re not yet an American, at least not in the modern sense. Instead, you’re a resident in one of Britain’s many overseas territories scattered across the vast American continent. The land stretching from the Atlantic coast westward encompasses diverse terrain and peoples. But what did people call this place? Your home? Not the “United States” for sure, because that term came later. Instead, it was a collection of British colonies, collectively referred to as the American colonies or the North American colonies.

A Sea of British Colonial Names

The term “American colonies” shows up in notable works of the era. Take, for example, publications from 1766:

- The Justice and Necessity of Taxing the American Colonies Demonstrated (London, 1766)

- The Grievances of the American Colonies Candidly Examined (London and Providence, 1766)

- Memorial on the General Culture of Lands in Our American Colonies (Edinburgh, 1766)

The frequent usage in political and economic treatises indicates that “American colonies” was a recognized term, primarily by the British and colonists themselves. It designated the English-speaking settlements along the eastern seaboard that were under British control.

But here’s a twist: Britain had a lot more territory in the Americas beyond these colonies. So, “American colonies” didn’t encompass everything under British rule on the continent. These colonies specifically referred to British territories that would eventually become the US, not including places like Canada or the Caribbean islands.

Distinguishing the Present-Day US Colonies from Other British Possessions

Before independence, British North America was a broad mosaic:

- Hudson’s Bay: Roughly today’s northern Canada.

- Labrador, Newfoundland, and Canada (including Quebec): Officially British, quite distinct culturally and politically from the southern colonies.

- Nova Scotia and the East and West Florida: Also British colonial possessions separate from the future United States.

- The Caribbean islands: Places like Jamaica and Barbados were important British colonies, but they weren’t part of what was called the American colonies because they aren’t on the mainland.

When you hear “American colonies” in the 18th century, it’s a shorthand for a very specific group of British possessions along the Atlantic coast — the territories that stubbornly began calling themselves something else in 1776. It marks a clear difference in identity from Canadian or Caribbean British colonies.

And What About the “Thirteen Colonies”?

It might surprise you, but the phrase “Thirteen Colonies”—now synonymous with the original states that rebelled—is a post-Revolution invention. There’s no record of people using this phrase before the war. Why? Because before independence, the colonies didn’t see themselves as a united group of thirteen siblings ready to rebel. They were separate entities, often competing with and suspicious of each other, despite sharing language and customs.

Only after the colonies declared independence and forged a new nation did the term “Thirteen Colonies” enter historical and political language. It’s like calling a high school basketball team the champions *before* they win the championship—not quite accurate!

The Bigger Picture: Why Do These Names Matter?

Now, you might wonder: Why should we care about these names? Names are powerful. They frame identity and influence politics.

Calling the land the “American colonies” subtly emphasized British authority and colonial status. It reminded colonists—and Britain—that these settlements were overseas extensions of the empire, not independent countries. Yet, this label carried the seeds of what was to come, embodying a shared identity among these colonies distinct from other British territories.

When the Revolutionary War started, colonists began imagining themselves as part of something bigger. Their terminology shifted alongside their politics. “Thirteen Colonies” became a rallying cry, a symbol of unity and common purpose. Eventually, “United States” emerged, signifying a new idea—not just possessions, but a nation forged in rebellion.

So, What Can We Take Away?

- The “present-day US” was not called the United States before 1776; it was generally known as the American colonies or North American colonies.

- These terms excluded other British territories like Canada, Newfoundland, and Caribbean islands, which held a separate identity.

- The phrase “Thirteen Colonies” only emerged after the American Revolution—showing how language evolves with political change.

- Names signaled power dynamics and identity; they framed how colonies saw themselves and each other.

Next time you read about the “Thirteen Colonies,” remember they were many separate pieces before they came together under that name. It’s a reminder that history is a story of change—not just in facts, but also in how people saw their world.

“Names not only identify but shape our history. Before independence, the land was British colonies. After, it became a nation.”

Curious about how other colonial powers named their territories or how that influenced modern identities? That’s a great question for another day.