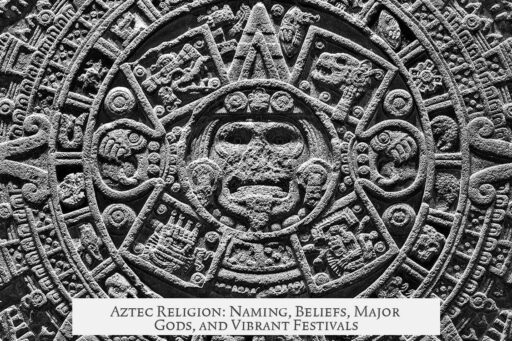

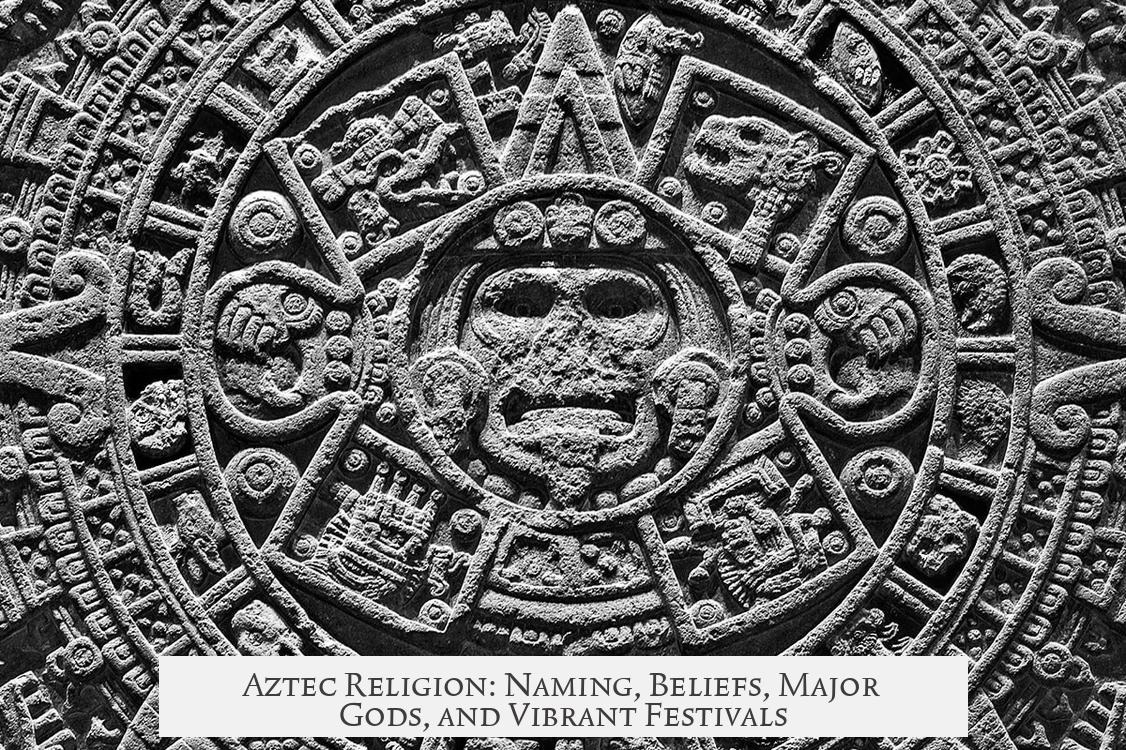

The Aztec religion did not have a single, specific name, as it functioned integrally with the society’s politics, economics, and philosophy. Commonly referred to as the Nahua religion, it reflected a polytheistic belief system deeply embedded in the daily and communal lives of the Aztec people. Their beliefs, rites, and festivals centered on multiple gods, varying across communities but often highlighting key deities like Huitzilopochtli, Tlaloc, Tezcatlipoca, and Quetzalcoatl.

The Aztec worldview blended religion with all aspects of life. Unlike in modern Western societies, there was no clear division separating religion from governance or social organization. The Nahua religion, named after the language group of the Aztecs, involved complex rituals that marked crucial moments such as childbirth, death, health, and seasonal cycles.

The Aztec calendar included eighteen major festivals, each dedicated to different gods and seasonal events. These religious holidays featured ceremonies led by a priestly class supported by local elites. Still, popular religion thrived with household rituals aimed at securing health, good weather, bountiful harvests, and community welfare. This made religion both a top-down and grassroots phenomenon inside Aztec society.

The Aztecs practiced polytheism, worshiping many gods. However, the prominence of gods varied by region and community. The Mexica people, who formed the empire’s core, honored Huitzilopochtli as their patron deity. This god of war and the sun was especially significant to the Mexica and symbolized their identity and military prowess. The main pyramid in Tenochtitlan held two temples—one dedicated to Huitzilopochtli—which highlights his importance.

Tlaloc, the rain god, was another major deity. His worship predates the Aztecs, going back over a thousand years to the civilization of Teotihuacan. Tlaloc represented rain, fertility, and agriculture. Almost every community considered him crucial because rain and harvests were essential for survival. In Aztec temples, including the tallest pyramid, Tlaloc received significant veneration alongside Huitzilopochtli.

Tezcatlipoca and Quetzalcoatl were also prominent gods. These two came from earlier Toltec mythology, in which they appeared as opposing figures—often described as a “good guy” and “bad guy.” The Aztecs favored Tezcatlipoca, the more fearsome and complex deity associated with conflict, destiny, and power. His temple was larger than Quetzalcoatl’s, and more myths about him survive in Aztec records. Over time, the Mexica adopted Toltec symbols and stories to strengthen imperial ideology, raising the status of these gods.

Huitzilopochtli stands out as the only purely Aztec god, embodying the Mexica’s martial spirit and identity. According to tradition, the Mexica worshipped him while roaming the arid northern regions before settling in the Valley of Mexico. This war god became the empire’s central figure for conquest and rulership.

Each community within the empire might emphasize different gods depending on local traditions and needs. This created a diverse but interconnected religious landscape. For example:

- Huitzilopochtli – war, sun, Mexica patron deity

- Tlaloc – rain, fertility, agriculture, universal across communities

- Tezcatlipoca – fate, conflict, power, favored in political symbolism

- Quetzalcoatl – wind, knowledge, culture, tempered prominence

This polytheistic system shaped Aztec life through rituals, sacrifices, and festivals. The eighteen major festivals often involved offerings to ensure cosmic balance and agricultural success. Rituals ranged from public ceremonies led by priests to intimate household practices safeguarding family wellbeing.

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Name | No distinct name; often called Nahua religion |

| Beliefs | Polytheistic, intertwined with daily life and governance |

| Major Gods | Huitzilopochtli, Tlaloc, Tezcatlipoca, Quetzalcoatl |

| Rites | Priestly ceremonies, household rituals, sacrifices |

| Festivals | Eighteen major religious holidays aligned with seasons and gods |

This structure reveals that Aztec religion served both practical and ideological roles. It justified rulership, promoted military expansion, and gave meaning to natural and social phenomena.

- No special name existed; the faith was part of wider cultural systems.

- Aztecs honored multiple gods but placed special emphasis on a few key deities.

- Huitzilopochtli symbolized war and Mexica identity.

- Tlaloc governed rain and fertility, vital for agriculture.

- Tezcatlipoca and Quetzalcoatl reflected older myths integrated into Aztec imperial theology.

- Rituals and festivals structured community life and reinforced societal hierarchies.

Aztec Religion: Naming, Beliefs, and Their Favorite Gods

Let’s start with the big question: Did the Aztecs have an actual name for their religion? The simple answer is no. Unlike modern religions with clear names and boundaries, the Aztec spirituality didn’t have a separate label. It was part of everything—politics, society, and daily life blended with their sacred universe. What we call the “Aztec religion” is more accurately the Nahua religion, reflecting the people who practiced it.

So why no specific name? They didn’t see religion as something isolated. Their world was a tapestry where gods, rulers, warriors, and farmers all played interlinked roles. Religion was the core of existence, not a compartment you could label like “Aztec faith.”

Diving Into Their Beliefs and Rites

The Aztec spiritual world was complex and colorful—full of multiple gods and dozens of festivals. They were polytheistic, meaning they worshiped many gods, each powerful and specific to different life aspects. But it’s important to note: which gods mattered more could vary widely across communities.

Picture this: every Aztec city or village organized grand festivals, some lasting days, celebrating sun cycles, harvests, rain, and war victories. In fact, historical records list eighteen major Aztec festivals tied closely to religious rites. These ceremonies typically involved priests who were trained elite specialists, supported by the local rulers.

Yet, beyond official rituals, Aztec religion thrived in everyday life. Families performed private ceremonies—prayers for healthy childbirths, good crops, or safe journeys. Their gods weren’t distant concepts but daily companions in hope and fear.

Who Were the Big Shots Among the Gods?

Not all gods got equal attention. Some towers of Tenochtitlan famously held twin temples dedicated to top deities. Here’s a quick introduction to the superstar gods, starting with the arguably most Aztec god: Huitzilopochtli.

- Huitzilopochtli: The hummingbird warrior god of war and sun was the Mexica’s patron. Mexica, a leading group in the Aztec Empire, believed he guided them from nomadic origins to empire builders. His temple stood proudly on the largest pyramid in Tenochtitlan’s center, symbolizing his supreme status.

- Tlaloc: The rain god had older roots, pre-dating the Aztecs. His worship continued from ancient Teotihuacan times—a civilization that thrived over a thousand years earlier. Tlaloc controlled fertile rains and harvests, making him essential across nearly all Aztec communities. His temple sat alongside Huitzilopochtli’s, underscoring his vital role.

- Tezcatlipoca and Quetzalcoatl: These two were legendary figures initially from Toltec myths integrated into Aztec lore. They played a cosmic “good guy/bad guy” role. Interestingly, the Aztecs seemed to favor the darker Tezcatlipoca—his temple was bigger, and more stories about him have survived. Both gods became central pieces in the Aztec imperial narrative as the Mexica merged Toltec traditions to legitimize their rule.

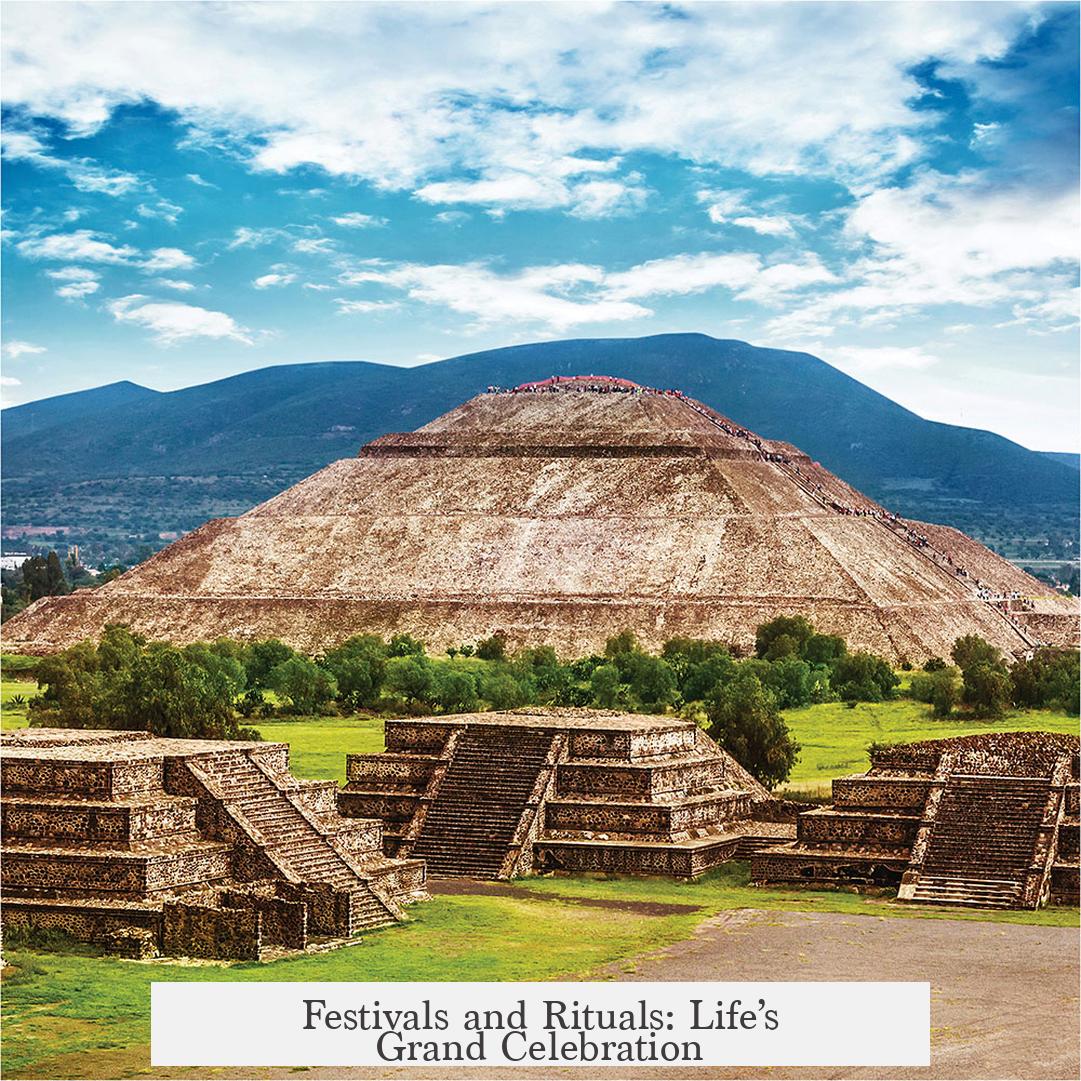

Festivals and Rituals: Life’s Grand Celebration

Imagine being surrounded year-round by vibrant festivals—each with distinct rites. Many involved offerings, music, dances, and sometimes, human sacrifices. For priests, these acts maintained cosmic balance and pleased gods to keep life flourishing. They believed the universe’s survival depended on feeding the gods, especially the sun god Huitzilopochtli.

Each festival was a vivid story painted in sweat, chants, and sacred blood—a high-stakes game where divine wrath and bounty balanced on mortal shoulders. People believed ignoring these rituals brought drought, plague, or defeat in battle.

A Dynamic Religious Mosaic

What’s fascinating is how flexible and local the Aztec religion was. There was no single script everyone followed verbatim. Different areas prioritized different gods, reflecting local needs and histories. While Huitzilopochtli and Tlaloc were broadly revered, communities worshipped their own patrons too.

This diversity shows religion wasn’t static—it evolved with politics, conquest, and culture. The Mexica adapted and absorbed older beliefs, emphasizing gods that supported their imperial goals. Hence, gods like Tezcatlipoca gained prominence as symbols of power and control.

Final Thoughts: What Can We Learn?

The Aztec religion teaches us that faith is woven with culture and survival. Their gods mirror life itself—war, rain, fertility, conflict, and creation. They carried no neat name for their beliefs because, for them, spirituality was life’s entire framework. Just like their grand festivals, their religion was a constant, living celebration—a reminder that behind ancient temples were people seeking meaning, protection, and hope.

Next time you hear “Aztec religion,” remember: it’s not just one thing. It’s a vibrant, shifting world where gods battle, rain falls, warriors march, and people pray—all under the same vast Mexican sky.