China’s early invention of gunpowder and firearms did not lead to lasting dominance in firearms innovation and production globally due to multiple technological, military, institutional, and cultural factors.

The origin of gunpowder in China began as a compound primarily valued for its incendiary effects rather than as a propellant. Early Chinese formulas emphasized slow combustion to generate heat and fire rather than rapid gas release needed for efficient projectile propulsion. The term huoyao, meaning “fire medicine,” reflects this initial understanding. Firearms like the fire-lance appeared in the 12th century but functioned more like incendiary bombs than guns as we define them today. Only by the late 13th century in northwest China did the first true hand-cannons emerge, marking the point when reusable tubes propelled projectiles using explosive charges.

Despite this early lead, China’s head start quickly diminished as gunpowder weapons rapidly spread westward, likely via Mongol contacts, reaching Europe where guns were documented by the 1330s. The European landscape, especially the nature of siege warfare, incentivized rapid and continuous firearms development. European fortifications, typically masonry walls not exceeding two meters in thickness, proved vulnerable to cannon fire, pushing states to improve artillery power aggressively.

In contrast, Chinese fortifications—characterized by thick earthen walls—were far more resistant to bombardment. Since cannon fire failed to provide significant advantages in breaching these defenses, there was less impetus to develop more powerful artillery. The Chinese military continued using gunpowder primarily for incendiary purposes alongside traditional siege engines like trebuchets to launch flaming projectiles over walls and onto wooden structures behind defenses.

This difference in siege warfare needs shaped divergent paths in firearms innovation. Europe’s frequent conflicts, including the Hundred Years’ War, continually drove the improvement and adaptation of guns and cannons. In East Asia, the military utility of firearms was perceived differently, and the strategic environment did not reward heavy investment in gunpowder artillery. This “Chinese Wall Thesis” explains how physical defenses influenced weapons development.

By the 16th and early 17th centuries, East Asian powers like the Ming dynasty, Korea, and Japan incorporated European firearms designs. Firearms technology was exchanged during this period, allowing East Asia to regrow technological parity with Europe. Portuguese and Dutch influences introduced advanced weapons, which East Asian states often adapted and combined with local innovations.

Following this phase of relative parity, East Asia entered an extended period of peace especially under the Qing dynasty, beginning in the mid-18th century. The so-called “Great Qing Peace” reduced the necessity for continuous military innovation. Major campaigns such as those against the Zunghars ended by 1757, and lasting stability persisted until the mid-19th century conflicts. With lower external threats, Chinese rulers had less motivation to modernize weaponry aggressively.

Yet this peace explanation is not fully sufficient. The Qing engaged in numerous costly military expeditions throughout the 18th century, including wars in Burma, the Jinchuan wars, and conflicts in Vietnam. Despite these, the Qing military did not invest notably in firearms modernization. Institutional factors likely contributed to this reluctance: the Qing state’s financial system lacked instruments like national debt, limiting modernization funding.

Additionally, political concerns played a role. The Qing regime hesitated to equip large numbers of Han Chinese soldiers with advanced weaponry, fearing potential rebellion. The ruling Manchu elite instead reinforced traditional military training focused on archery and horsemanship. Institutional conservatism and ethnic politics slowed adoption of new military technologies.

Technical capacity also matters. China faced challenges in metallurgy, technical drawing, and ballistic measurement. These skills were critical for advanced firearms production. Limitations in these technical fields impaired China’s ability to innovate and mass-produce improved guns, especially compared to European advances that combined scientific methods with industrial-scale production.

Broader geopolitical and cultural differences shaped innovation rates. China dominated East Asia as a regional superpower with fewer peer rivals, experiencing long intervals of peace. Europe remained fragmented into many smaller states that frequently fought one another, creating continuous pressure to innovate military technologies to gain advantage. This dynamic fostered rapid firearms improvement.

The divergence between China and Europe in firearms technology, therefore, emerges from a complex interplay of military needs, physical environment, political and institutional factors, technological ability, and international competition. Early technological head starts rarely guarantee permanent supremacy. Innovation depends on ongoing incentives, resources, and social-political conditions that vary over time.

| Factor | Impact on Chinese Firearms Innovation |

|---|---|

| Initial Gunpowder Use | More incendiary than propellant; delayed development of effective firearms |

| Fortification Type (Chinese Wall Thesis) | Thick earthen walls resistant to bombardment, limiting artillery incentives |

| Military Conflict Environment | Less frequent large-scale warfare reduced urgency for continuous innovation |

| Technical Capacity | Limited metallurgy and ballistics slowed weapon efficacy advancements |

| Institutional & Political Factors | Funding constraints and distrust of arming Han soldiers hindered modernization |

| European Peer Competition | Persistent state conflict drove rapid arms improvements and mass production |

- Gunpowder began as an incendiary compound with slow combustion, limiting early firearms use in China.

- Chinese fortifications resisted cannon fire better than European masonry walls, reducing artillery emphasis.

- Less frequent warfare in East Asia decreased the pressure for continuous firearm innovation.

- Technical and institutional limitations slowed China’s capacity for weapon advancements after the 17th century.

- Political distrust of arming certain populations reduced modernization incentives during Qing rule.

- Europe’s fragmented and competitive political scene fostered more rapid and continuous firearms innovation.

Why Didn’t China Dominate Global Firearms Innovation Despite Inventing Gunpowder and Guns?

It’s true that China gave the world gunpowder and even some of the earliest firearms, but this didn’t result in a sustained legacy of Chinese dominance in firearm innovation or production. So, why did this happen? Let’s unpack this fascinating historical puzzle.

If you expect a straightforward story—“China invented it, so China perfected it”—then history has some surprises for you. China’s early gunpowder was not quite what we imagine today. Initially, it was a *fancy incendiary* rather than a powerful explosive or propellant as in modern firearms.

The early Chinese term for this concoction, huoyao or “fire medicine,” perfectly captures its initial use: more like a chemical candle than a cannonball launcher. Early mixtures focused on slow, steady combustion, not rapid gas expansion needed to launch bullets.

By the 12th century, the fire-lance—think “bomb on a stick”—emerged. It evolved into a more complex weapon, sometimes hurling shrapnel, but it didn’t use reusable tubes firing solid projectiles as we understand guns today. The true ancestors of guns, small hand-cannons, appeared only in northwest China by the 1280s.

Europe’s Gunpowder Leap and the Early Spread of Firearms

The Mongol Empire helped spread gunpowder westward. By the 1330s, Europe had guns in its arsenal and soon used them extensively during major conflicts like the Hundred Years’ War.

China’s initial advantage faded quickly as Europe rapidly absorbed and developed firearms technology. Why? This leads us to the structural differences that shaped innovation trajectories.

The Chinese Wall Thesis: Defense Architecture Influences Firearms Development

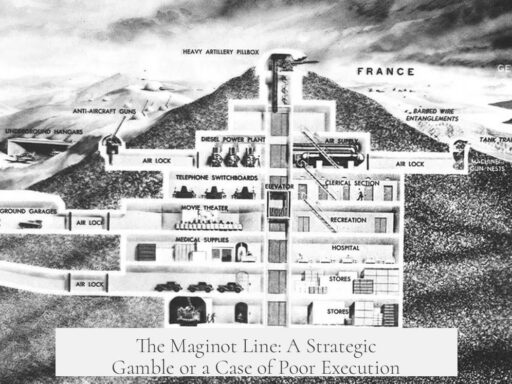

Here’s a juicy detail: Chinese city walls were thick earthworks, several meters thick, hard to break with early cannon fire. European city walls, on the other hand, were thinner masonry—more brittle under cannon impact. Europeans had a practical motivation to build increasingly powerful cannons, since their walls were vulnerable.

So, while Europe saw a clear military benefit to perfecting artillery, China continued relying on traditional siege engines like trebuchets, using gunpowder mainly for incendiary purposes. There wasn’t the same push to develop bigger, better cannons because the existing walls resisted bombardment very well.

Cultural and Military Priorities Shape Technological Paths

Culturally, Chinese sieges targeted wooden structures atop walls, such as crenellations, rather than the walls themselves. This mindset limited the perceived need for more devastating artillery innovations. If the walls were “good enough,” why rock the boat?

The balance of power in East Asia also contributed. China held a dominant position much of the time, facing fewer peer rivals compared to the fractious and competitive states of Europe, which constantly fought. More frequent wars in Europe meant more opportunities and pressures to innovate militarily.

East Asia Catches Up (Sort of) but Then Slows Down

Fast forward to around 1600. The East Asian states, including Ming China, Joseon Korea, and Japan’s warlords, began importing and adapting Portuguese and Dutch firearms. Coastal trade routes facilitated this exchange, enabling them to keep pace with Europe for a while.

This period was a kind of Renaissance for East Asian gunpowder weapons technology, involving domestic innovations and incorporating foreign designs. But this parity didn’t last.

The ‘Great Qing Peace’ and Stifled Innovation

One major explanation for the slowdown in firearms innovation after 1700 is the long period of peace known as the “Great Qing Peace.” From roughly 1757 to the early 19th century, China experienced relative internal stability with fewer large-scale conflicts threatening its borders—until the Opium Wars disrupted this calm.

Peace often means less incentive to push military technology forward. Why spend resources on expensive new weapons when no one’s shooting at you? This lack of urgency stood in contrast to Europe’s turbulent political climate, which constantly demanded better arms.

But Wait, What About Qing Military Campaigns?

Here’s a puzzle: The Qing dynasty still launched several massive military campaigns in Burma, against hill tribes, and in Vietnam during the late 18th century. They spent huge sums showcasing martial power, yet they didn’t invest heavily in firearm innovation during or after these campaigns.

This suggests that the pause in firearms advancement wasn’t purely about peace. Instead, there were deeper institutional and technical reasons.

Institutional and Technical Roots of Chinese-European Divergence

China’s industrial and technical capacity lagged in key areas. Skills like metallurgical refinement, technical drawing, and ballistic measurements—foundations of effective arms production—were less developed or deprioritized.

On the financial side, the Qing government ran a low-tax regime without instruments like national debt to fund large-scale innovation and industrialization. In contrast, European states mobilized capitals for military advancement more easily.

Ethnic and political concerns also played a role. The Qing elite, often Manchu, favored traditional martial arts such as archery and horse-riding, sometimes questioning the loyalty of Han Chinese troops. This may have reduced incentive to equip them with advanced firearms aggressively.

The situation calls for re-examining why divergence occurred earlier, between 1400 and 1550. Institutional factors shaping innovation—or lack thereof—seem as critical as technical abilities.

Bigger Picture: Warfare Environment and Innovation Dynamics

Imagine Europe as a constant battleground of peer powers, always pushing each other to get better weapons or suffer defeat. In East Asia, a dominant power loomed, keeping rivals at bay. Innovation thrives in competition, especially when states are closely matched and conflicts frequent.

China’s stable but less competitive warfare environment changed the rules for firearms innovation.

Lessons and Takeaways

- Initial invention doesn’t equal perpetual dominance: China’s early lead in gunpowder didn’t guarantee they’d stay on top forever. Technological head starts can evaporate.

- Context is king: Physical defenses, warfare style, cultural priorities, and political structures all influence technological evolution.

- Economic and institutional power matters: Availability of resources, skilled artisans, and government will strongly affect innovation.

So where does this leave us?

China set the stage by inventing gunpowder and guns but lacked the conditions that pushed Europe to turn firearms into dominant military tools and mass-produced weapons. The story isn’t just one of technology but of society, policy, culture, and necessity.

Next time you think about who leads innovation, ask: What pressures and incentives shape their ideas? Inventing the spark is one thing. Fanning it into a blazing, unstoppable fire is quite another.

China’s journey with gunpowder reminds us: innovation isn’t just about invention—it’s about environment.

Curious about other inventions that took off in some places but stalled in others due to similar reasons? History is full of these “what if” moments shaped by more than just clever minds.

Why didn’t early Chinese gunpowder technology lead to sustained innovation in firearms?

Early Chinese gunpowder was mainly used as an incendiary, not optimized for launching projectiles. This limited early firearm development. Also, thick Chinese walls resisted cannon fire, reducing pressure to improve guns for siege warfare.

How did differences in fortification design affect firearms innovation in China and Europe?

Chinese walls were thick earthworks that could resist cannon bombardment. European walls were thinner masonry and vulnerable. Europe had a strong reason to develop powerful cannons, while China relied more on other siege methods.

Did cultural or military priorities influence China’s firearms development?

Yes. Chinese military favored traditional siege engines like trebuchets for burning targets behind walls rather than destroying walls. This limited incentives to innovate more destructive artillery.

Why did China fall behind Europe in firearms innovation after 1600 despite exchanges of technology?

Peaceful conditions during the Qing era decreased military innovation pressures. Institutional limits, such as low taxation and political concerns, reduced investment in weapon modernization despite ongoing campaigns.

Could institutional factors explain China’s decline in firearm dominance?

Yes. The Qing state lacked financial tools for sustained modernization and may have distrusted arming Han soldiers. Priority given to traditional martial arts over firearms also hindered advancement.