The 1997 film “Seven Years in Tibet” combines true historical events with dramatized and condensed storytelling, resulting in an uneven portrayal of Heinrich Harrer’s experiences and Tibetan history. While based on Harrer’s memoir, the movie omits significant details, alters timelines, and simplifies complex contexts for cinematic purposes.

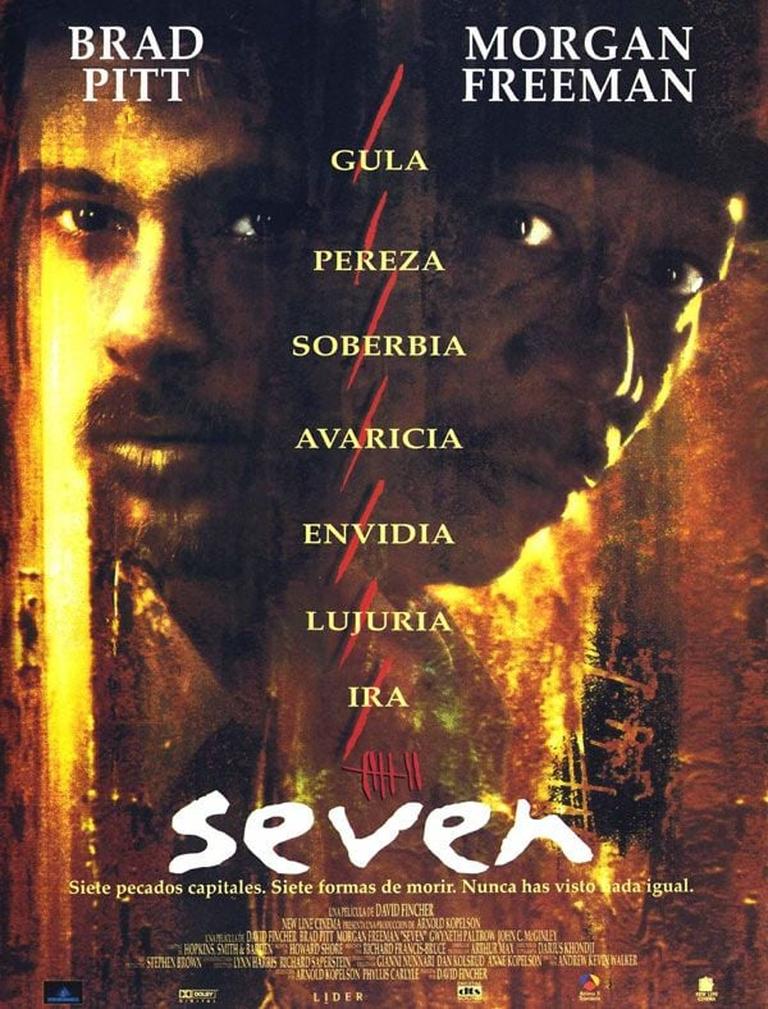

The film compresses over seven years of Harrer’s life into less than two hours, inevitably sacrificing nuance. Hollywood’s choice to cast Brad Pitt as Harrer brings star power but can overshadow historical reality. Pitt’s portrayal emphasizes personal transformation, which partly distorts Harrer’s complex past, especially regarding his Nazi connections.

One major inaccuracy is the downplaying of Harrer’s membership in the SS. Harrer openly admitted to joining the SS but described it as “youthful folly” with minimal political engagement or participation in combat. The movie avoids this controversial aspect, likely to maintain audience sympathy for the protagonist.

The depiction of Harrer’s prison camp experience exaggerates the harshness. Unlike the film’s more brutal and violent portrayal, Harrer’s memoir mentions primarily food shortages and lacks accounts of prisoner violence. This discrepancy likely serves to justify dramatic escape sequences and increase tension.

Several adventures that Harrer and his companion Peter Aufschnaiter underwent during their journey through Tibet are omitted. For example, their stay in Kyirong village, called “The Village of Happiness,” and their subsequent forced departure due to Tibetan authorities’ suspicions, does not appear in the film. Additionally, an encounter with the Khampa tribe—with a tense scenario involving potential violence—gets left out. These omissions reduce narrative complexity and simplify the journey into a straightforward flight to safety.

The film also presents small inaccuracies, such as portraying Harrer and Aufschnaiter arriving in Lhasa with beards to pass as Kashmiri traders. While it is true they wore disguises to avoid detection, the exact details of their appearance and the effectiveness of this disguise are simplified.

Certain aspects of Harrer’s time in Lhasa are accurately shown. For instance, Harrer and Aufschnaiter did reintroduce ice-skating to Tibetans, who referred to it as “walking on knives.” Harrer also tutored the young 14th Dalai Lama in English, geography, and technology, reflecting the Lama’s keen interest in mechanical devices and engines. However, the relationship between Harrer and the Dalai Lama receives romanticized embellishments, making their connection seem closer and more personal than accounts suggest.

Perhaps the most distorted sequence in the movie is the depiction of the Battle of Chamdo and the Tibetan military. The film shows the Chinese army as a massive, well-equipped force overpowering a ragtag group wielding bows and arrows. This portrayal is both historically inaccurate and misleading. In reality, by 1950, the Tibetan army had undergone substantial modernization under the 13th Dalai Lama’s reforms—equipped with rifles and artillery—making the actual conflict vastly different. The film’s anachronistic depiction resembles propaganda rather than fact, obscuring Tibetan military capabilities and the complex political circumstances.

| Aspect | Film Portrayal | Historical Reality |

|---|---|---|

| Harrer’s SS Membership | Downplayed or omitted | Admitted member, minimal political activity |

| Prison Camp Experience | Violent and harsh conditions | Food shortages, less violent |

| Journey Adventures | Significant omissions (Kyirong, Khampa tribe) | Detailed accounts of incidents and escapes |

| Disguise in Lhasa | Bearded Kashmiri trader disguise | Wore disguises, beard detail uncertain |

| Interaction with Dalai Lama | Close personal tutor relationship | Tutored in English/geography, modest relationship |

| Battle of Chamdo | Overwhelming modern Chinese vs. primitive Tibetans | Tibetan army modernized and better equipped |

The movie succeeds in bringing greater public awareness to Tibet during a turbulent historical era. However, by simplifying events, omitting politically sensitive details, and prioritizing storytelling, it sacrifices accuracy. Scholars and historians caution viewers to see the film as a dramatized narrative rather than a reliable documentary. Harrer’s own memoir remains a more nuanced source, though it too reflects personal bias.

Overall, “Seven Years in Tibet” achieves dramatic impact but fails to fully represent the complexities of the era, the political tensions involved, and the real character of Harrer. It overlooks significant incidents and alters critical facts, producing a story that is inspirational but not fully factual.

- The film condenses seven years into two hours, losing historical detail.

- Harrer’s Nazi SS membership is largely hidden or downplayed.

- The harshness of imprisonment is exaggerated.

- Many adventures during the trek to Lhasa are omitted.

- The Tibetan army is inaccurately portrayed as primitive.

- Harrer’s tutoring of the Dalai Lama is partly accurate but romanticized.

- The film prioritizes drama over precise historical truth.

Are the Events Depicted in the 1997 Movie “Seven Years in Tibet” Historically Accurate?

If you’re wondering whether the 1997 film “Seven Years in Tibet” sticks to the straight and narrow of history, the short answer is: not exactly. The movie draws inspiration from Heinrich Harrer’s memoir but takes creative liberties that shuffle the facts for cinematic flair. Let’s unpack this tale of mountaineering, political upheaval, and cultural encounters to see where Hollywood hit the mark and where it took some scenic detours.

Many viewers expect historical films to offer a documentary-style recounting. However, “Seven Years in Tibet” fits comfortably into the category of dramatization. The filmmakers need to squeeze more than seven years of rich, complex experiences into less than two hours. That’s a tall order, so things get condensed and simplified.

For starters, casting Brad Pitt as Heinrich Harrer is both a blessing and a curse. Brad is a great actor, but his star power sometimes overshadows the real person behind the story. You can’t help but see “Tyler Durden” in the mountaineer’s shoes instead of the layered, flawed historical figure. Hollywood loves to trade nuance for familiarity, and Pitt’s casting exemplifies that trend.

Now, about Heinrich Harrer himself—here’s where the film sidesteps a major historical detail. Harrer’s membership in the SS is barely mentioned, if at all. In reality, Harrer admits his association but downplays it, framing it as youthful folly while emphasizing his true passion: mountaineering. He stayed away from combat and wartime activities. The movie, however, mostly ignores this, perhaps to maintain his heroic aura and avoid awkward political conversations.

Speaking of drama, the way the movie portrays Harrer’s imprisonment and escape ramps up tension. The prison camp feels harsher and more violent on screen than Harrer’s memoir suggests. While food shortages did occur, the intense brutality shown is likely a Hollywood invention to justify Harrer and his companion’s daring escape. Filmmakers create clear antagonists and high stakes, even if that means stretching the truth.

On their way to Lhasa, Harrer and his friend Peter Aufschnaiter experience many adventures the movie skips. For example, they pass through Kyirong, also known as the “Village of Happiness,” where the locals initially show kindness. However, Tibetan authorities eventually plan to deport them, prompting the duo to leave feeling betrayed. This subtle nuance shows the complicated social dynamics Harrer faced, which the film glosses over.

Another omitted episode: the duo’s barely-escaped encounter with Khampa tribesmen intent on violence and robbery. Harrer and Aufschnaiter detect the danger and flee. This detail adds sharp edges to their journey across Tibet’s rugged landscape, but it didn’t survive Hollywood’s edit.

Minor details matter, too. In the film, Harrer and Aufschnaiter’s bearded appearances last through their arrival in Lhasa. Historically, after months without shaving, locals mistook them for Kashmiri traders. This disguise helped them integrate and avoid suspicion—a clever survival tactic omitted on screen.

On the positive side, the film captures some authentic moments. Harrer and Aufschnaiter did reintroduce ice-skating to Tibetans, who refer to it as “walking on knives.” It’s a quirky cultural tidbit that grounds the film in reality. Harrer also tutored the young Dalai Lama, teaching him English, geography, and insight into mechanical devices. HHDL’s curiosity about machines like watches and movie projectors adds a fascinating dimension gone underexplored in the film.

However, the movie’s portrayal of the Battle of Chamdo is a low point for historical accuracy. It shows a stark mismatch: a massive modern Chinese army versus a Tibetan militia armed mostly with bows and arrows. This depiction borders on absurdity. Tibet had modernized its military decades earlier, a fact the film overlooks entirely. Painting the Tibetan soldiers as primitive fighters does a disservice to history and feeds into harmful stereotypes, which even decades before had little grounding in reality.

So what’s the takeaway? Should we toss “Seven Years in Tibet” into the rubbish bin of historical fiction? Not quite.

The film is a compelling narrative with impressive cinematography and a heartfelt story. It opens a window into Tibet’s culture and the extraordinary friendship between Harrer and the Dalai Lama. But it’s essential to remember: it’s Hollywood’s lens, not a history textbook.

For those curious about the real story, here’s a quick checklist to keep in mind:

- Expect Condensation: Seven years becomes two hours of storytelling magic.

- Real People, Hollywood Faces: Casting decisions can amplify certain traits while muting others.

- SS Membership is Downplayed: Harris’s political past is less visible in the film than in reality.

- Prison Camp Drama Amplified: Imprisonment conditions were less brutal than portrayed.

- Ignored Adventures: Several tense and fascinating episodes en route to Lhasa are skipped.

- Minor Details Matter: Disguises and cultural exchanges are altered or simplified.

- Accurate Intricacies: Ice-skating reintroduction and HHDL’s mechanical interests stay true to history.

- Battle of Chamdo is Distorted: Tibetan military strength is unfairly misrepresented.

Curious readers might consider reading Harrer’s original memoir or exploring reliable historical sources to gain a more nuanced view of Tibet during this tumultuous time. The movie is a good starter but not the final word.

At the end of the day, “Seven Years in Tibet” blends history with storytelling. It sparks interest but encourages us to dig deeper, question more, and appreciate the contrast between film and fact. How often do you let a movie inspire your curiosity to learn the full story?