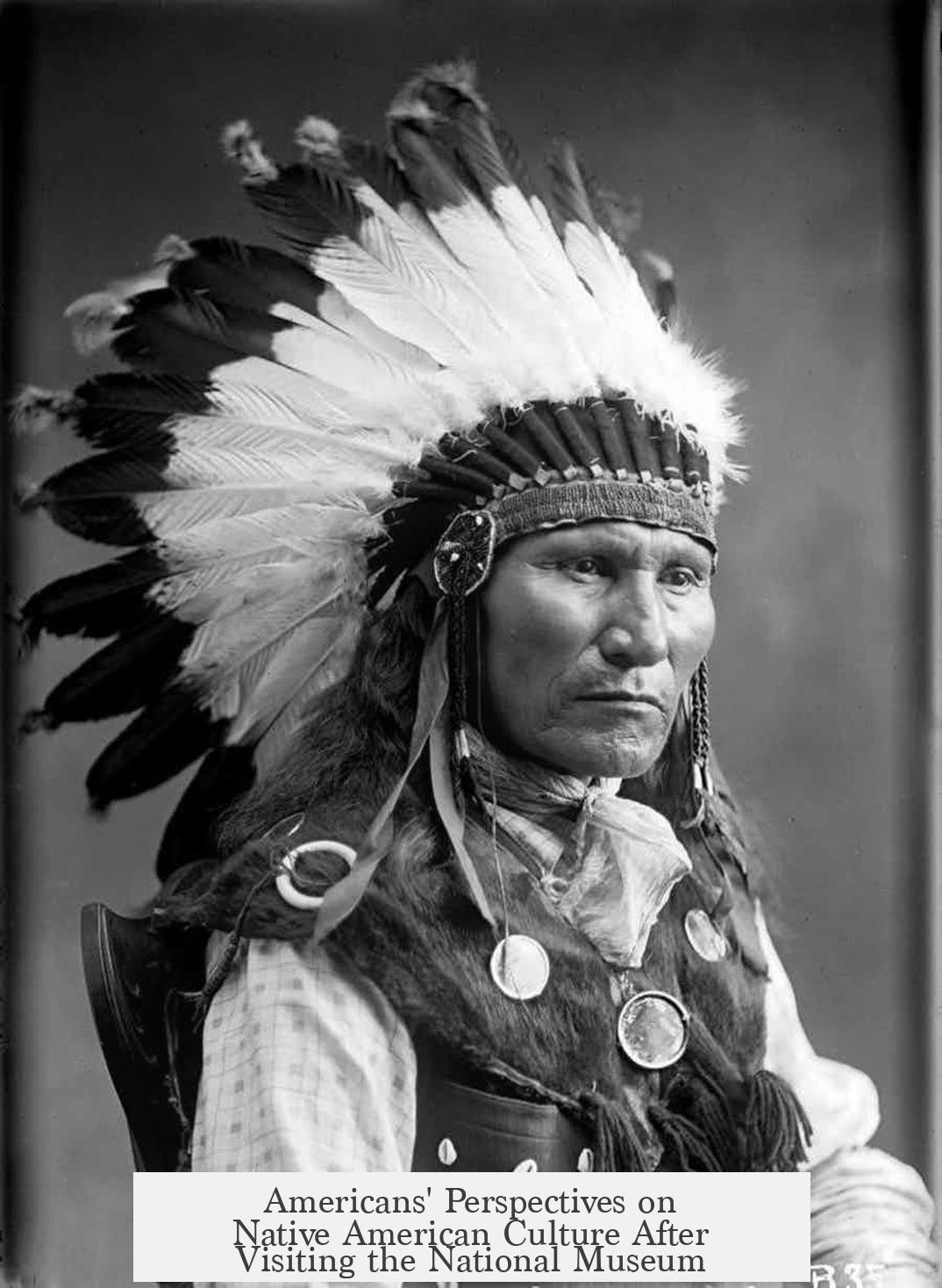

Americans hold a complex and evolving view of Native Americans, shaped by history, law, culture, and education. The National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) reflects parts of this narrative but also highlights ongoing challenges in representation, public understanding, and institutional priorities.

The NMAI serves as a focal point for how Native Americans are perceived and presented. Despite its importance, the museum’s exhibitions have not been significantly updated since the 1990s. This limits its ability to fully reflect contemporary understandings or address difficult aspects of Native American history and culture effectively.

Although the museum has worked in recent years to improve ties with Native communities, this progress is not yet visible to visitors. Constraints around funding and the Smithsonian’s prioritization mean that major exhibition overhauls for NMAI lag behind other museums like the National Air and Space Museum or the National Museum of Natural History. These financial and institutional factors influence the public’s exposure to Native perspectives and historical complexities.

The museum also wrestles with terminology, especially around the use of “American Indian” versus “Native American.” The term “American Indian” remains legally and politically significant, as federal recognition and treaty rights hinge on it. Tribes themselves use this term formally, though opinions on its use vary among Native individuals. This reflects the broader challenge of balancing legal language, personal identity, and public perception.

NMAI’s exhibitions sometimes show Native American-European interactions in ways that appear sanitized. For example, suggesting Native peoples welcomed European trade opportunities overlooks the coercion and conflict involved. However, historians emphasize the mixed experiences—colonial encounters were partly voluntary, partly destructive, and also generative in creating new societies. This nuanced view is essential to understanding Native American history beyond a simple narrative of loss.

The museum, as a federal institution, operates within political limits. For instance, it avoids labeling historical colonial violence explicitly as genocide, instead using terms like “cultural genocide” which lack legal weight but allow acknowledgment of harms without challenging national myths. This highlights how government institutions must navigate sensitive historical topics carefully.

Contemporary views about Native Americans also vary widely across the U.S. Many Americans lack a clear understanding of tribal sovereignty, legal recognition, or the diversity of Native peoples. Some mistakenly believe Native Americans no longer exist. Education about tribal governments and cultures is uneven, depending largely on regional proximity and local history.

Tribes today exercise significant sovereignty as “domestic dependent nations” with their own governments and laws. For example, in Washington State, tribes are major employers and have formal roles in state governance. Tribal economic contributions and political engagement challenge outdated stereotypes and underscore Native communities’ resilience and leadership.

Federal apologies have acknowledged past harms such as federal boarding school abuses. While symbolically important, these gestures often lack concrete restitution or reconciliation programs at a national scale. The presence of Native American Secretary of the Interior and initiatives investigating historical injustices mark steps forward in government recognition.

Military service is another area shaping Americans’ views. Native Americans serve at the highest per capita rates in the U.S. military, a fact reflected in museum exhibits and public awareness. This complicates simplistic images of Native peoples solely as victims of history.

Finally, reservations, often misunderstood, represent both sites of forced removal and vital land bases where tribes exercise sovereignty. Presenting them accurately requires recognizing both their origins in coercive federal policy and their ongoing importance to Native identity and governance.

| Aspect | Summary |

|---|---|

| National Museum of the American Indian | Exhibits outdated but efforts made to improve Native community involvement; funding limits updates. |

| Terminology | “American Indian” is a legal term still widely used; “Native American” preferred by some but varies. |

| Historical Views | Colonial interactions complex; museums tread carefully around terms like “genocide.” |

| Public Awareness | Varies widely; misconceptions about Native Americans persist; tribal sovereignty often misunderstood. |

| Contemporary Issues | Tribes are sovereign nations with political and economic influence; federal apologies symbolic but limited. |

- Americans’ views are diverse, shaped by limited and evolving museum narratives, legal frameworks, and education.

- NMAI reflects both progress and funding constraints limiting public engagement with Native perspectives.

- Terminology around Native identity remains complex, influenced by legal and personal meanings.

- Historical representation often balances acknowledgement of violence with sensitivities tied to national identity.

- Contemporary Native sovereignty and contributions challenge outdated perceptions and highlight active Native presence.