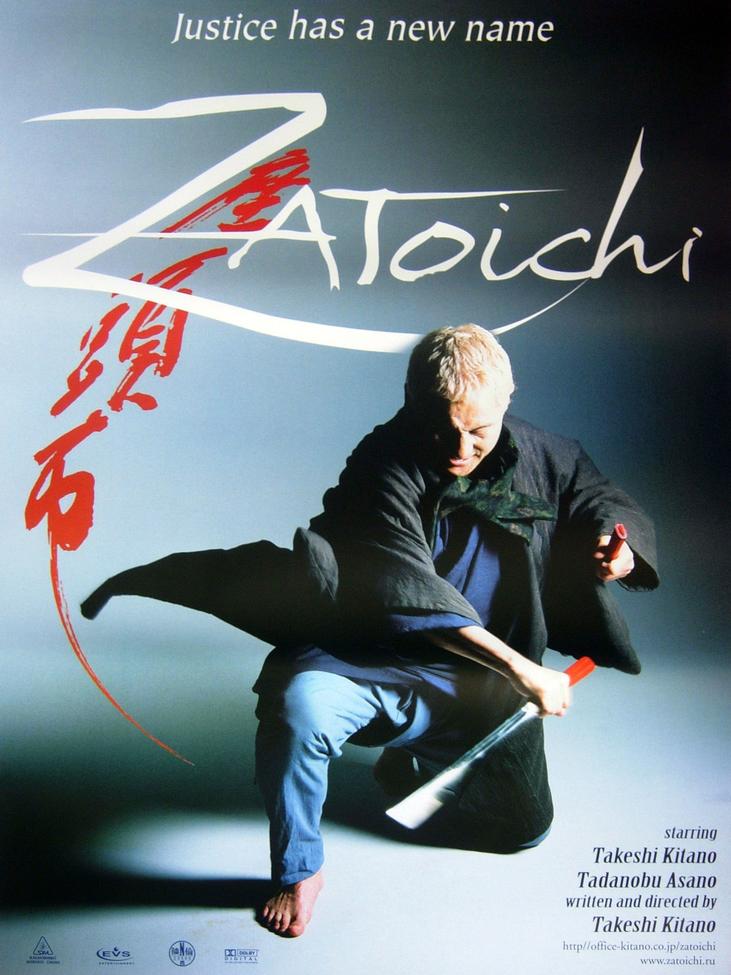

The Zatoichi series portrays Edo period Japan with a mix of historical accuracy and creative liberties, reflecting aspects of life for blind masseurs, village activities, and gambling, while occasionally stretching facts for dramatic effect.

Zatoichi’s profession as a blind masseur aligns well with historical realities. During the Edo Period, being a masseuse was one of the few professions legally reserved for blind people. This legal exclusivity cemented the strong association between blindness and massage in Japanese culture.

Blind individuals also held another distinct role: reciting epics and songs, usually performed by blind women. These professions formed organized guilds with hierarchical structures. The guild leaders often amassed significant wealth, revealing a unique social dynamic.

The series accurately situates Zatoichi within this occupational framework, reflecting an authentic social niche for blind persons at the time.

The depiction of gambling, fighting, and prostitution in villages in the series has mixed accuracy. These activities were largely illegal across Japan but persisted in regulated or marginal forms. Small villages lacked the wealth and population density to support formal establishments like licensed gambling houses or brothels.

Informal or private gambling games, occasional fistfights, and independent prostitutes probably existed at the village level. However, these would be small-scale and unofficial, often overlooked unless becoming major social issues. This context matches the Zatoichi series portrayal, where such activities are visible but not formalized.

Regarding archery booths, the series depicts these similar to modern fair-style attractions, but historical evidence is weak. The bow and arrow symbolized samurai power, and the Tokugawa Shogunate strictly limited arms ownership to maintain control. Public archery booths would thus be highly unusual or absent, contradicting the series portrayal.

The gambling scenes featuring loaded dice carry partial truth. Weighted dice and cheating in gambling appear in Japanese literature and yakuza lore. Criminal groups often ran gambling dens, and cheating was a known risk. However, maintaining customer trust typically discouraged overt cheating like loaded dice.

Formal game rules generally gave houses a slight edge without flagrant deception. Thus, the series’ gambling portrayals fit traditional narratives but may overemphasize the use of loaded dice for dramatic tension.

Zatoichi’s self-identification as “Yakuza” is likely anachronistic. The term “yakuza” originated after Edo Period, and criminal groups during that era did not use this label. This choice likely serves modern storytelling rather than historic exactness.

Overall, Zatoichi captures many aspects of Edo period life, especially the marginal world of itinerant blind masseurs and village underworld interactions. Yet, it incorporates stylized elements and some historical inaccuracies for narrative effect.

For example, classic cinema like Akira Kurosawa’s Red Beard offers a more grounded depiction of late Edo life, focusing on social order and daily struggles rather than sensational drama.

| Aspect | Accuracy in Zatoichi Series |

|---|---|

| Blind profession as masseuse | Highly accurate; legally restricted to blind practitioners |

| Village gambling, fighting, and prostitution | Partially accurate; informal but regulated and limited in villages |

| Archery booths like fairs | Unlikely; conflicts with strict arms bans and samurai symbolism |

| Use of loaded dice in gambling | Possible but often discouraged; overemphasized in drama |

| Zatoichi calling himself “Yakuza” | Anachronistic; term did not exist in Edo period |

- Zatoichi’s role reflects authentic blind occupations of Edo Japan.

- Village life depiction of illegality is nuanced; unofficial activities likely persisted.

- Archery booth portrayal contradicts historical arms restrictions.

- Gambling cheating narrative matches folklore but adds dramatic license.

- The term “yakuza” is historically out of place during Zatoichi’s era.

The Accuracy of the Zatoichi Series: Balancing Fact with Fiction

So, how accurate is the Zatoichi series when it comes to portraying Edo period Japan? The answer: it’s a mix of solid historical foundations sprinkled with dramatized liberties. Zatoichi, the blind masseuse who moonlights as a swordsman, draws from some genuine Edo period realities, but the story’s flair often strides beyond strict historical accuracy.

Let’s unpack the layers behind the famed series, separating the historical gems from the cinematic embellishments.

Blind Masseuse: Historically On Point

To begin with, Zatoichi’s profession as a blind masseuse is genuinely rooted in history. During the Edo period, becoming a masseuse (or masseur) was one of the few legal professions designated strictly for the blind. This wasn’t just tradition, it was law. By the mid-Edo period, blind people basically had a monopoly on massage therapy. The portrayal of Zatoichi practicing in this field is spot on and reflects the societal structures of the time.

Interestingly, blind professions did not end with massage. Another notable occupation involved the recitation of epics and songs, often performed by blind women. These professionals were members of guilds—highly organized and governed societies—and the male heads of these guilds amassed considerable wealth. So, next time you watch Zatoichi deftly feeling his way through a massage, remember that this narrative detail actually echoes a real historical framework.

Village Life: Gambling, Fighting, and Whoring – Realistic or Exaggerated?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EACCsLH3ZKI

If you expect Edo period villages to be wild dens of unregulated gambling, fistfights, and thriving whorehouses just like Zatoichi shows, think again. Small villages during this era were typically currency-poor and largely subsistence-based, paying taxes often in rice or grain. This economic reality limited the establishment of formal gambling halls or brothels.

While gambling, prostitution, and brawling were generally **illegal** across Japan, they did not entirely vanish. Small-scale, private acts—like an impromptu fistfight or a discreet gambling game—probably happened. But institutionalized or commercialized versions? Those belonged to larger towns or cities with enough wealth and a sufficiently large population.

This means the Zatoichi series amplifies these vices in villages for dramatic tension, yet small-scale informal activities are quite plausible. So, think of it as “historically inspired” with a dash of cinematic convenience.

Archery Booths: A Case of Creative Liberty

The series sometimes features archery booths reminiscent of modern fair games. However, there’s little evidence that such booths existed during Edo. At the time, archery was closely intertwined with samurai culture—it symbolized martial prestige and status. Plus, the Tokugawa Shogunate enforced strict arms bans to maintain control over violence.

Hence, archery booths, especially as casual public amusements, would have been rare or outright disallowed. They certainly wouldn’t have been a permanent fixture in villages or towns. The archery scenes in Zatoichi fall more into the realm of creative liberty, adding to the setting’s flavor but not historical accuracy.

The Dice Are Loaded… Or Are They?

Gambling scenes in Zatoichi often feature loaded dice or other cheating tactics. Japanese literature and history do include references to weighted dice, especially in yakuza-run gambling. However, from a business perspective, blatant cheating is a bad long-term strategy—if gamblers catch on, they just go elsewhere.

Most gambling operations relied on subtle house advantages embedded in game rules rather than risky outright cheating. The yakuza biography testimony supports this: “Loaded dice are a bad idea because customers will leave if they feel cheated.” This balanced approach between fairness and advantage appears to hold true.

The Zatoichi series plays up the cheating angle for tension, but historically, the scenario is a bit more nuanced.

Yakuza: When Words Don’t Quite Fit History

Zatoichi sometimes identifies himself as “yakuza,” but this is historically improbable. The term “yakuza” began as a derogatory label meaning “bad luck” and was not used by the criminal gangs themselves during the Edo period. It emerged later in common parlance, long after the setting of the Zatoichi series.

Organized gangs existed, of course—roles parallel to modern yakuza—but they didn’t self-identify with this word, nor did they necessarily share our contemporary understanding of the yakuza’s cultural meaning.

Calling Zatoichi a “yakuza” is likely an anachronism, a case of modern terminology retrofitted for audience comprehension.

Wider Edo Period Portrayals: Zatoichi vs. Kurosawa’s “Red Beard”

While Zatoichi gives us a thrilling, action-packed glimpse into Edo life with a unique protagonist, it leans heavily on myth-making. For a more grounded representation of the period’s daily life, Akira Kurosawa’s movie Red Beard offers outstanding realism.

Unlike Zatoichi, it avoids samurai legend and “one-man army” narratives. Instead, it focuses on mundane existence, social status, and human relationships—depicting what life truly felt like for common folk. So if you want the Edo period’s mundane reality beyond sword fights and quickdraws, “Red Beard” is a great contrast.

Summing It Up: Zatoichi’s Accuracy Unpacked

- The blind masseuse angle is historically accurate and well-researched. Edo laws reserved massage therapy exclusively for the blind.

- Depictions of gambling, fighting, and prostitution in villages are partly exaggerated. While informal versions existed, formal establishments were unlikely in small, poor villages.

- Archery booths are creative fabrications. Archery’s samurai symbolism and tough arms bans make permanent archery games unlikely.

- Loaded dice cheating, though possible, was not widespread due to smart gambling economics. The house relied more on rules favoring the dealer than risky card or dice switching.

- Labeling Zatoichi or others as “yakuza” is anachronistic for the Edo period. The term’s usage came much later and wasn’t embraced by gangs themselves then.

- For everyday life realism in Edo Japan, films like Kurosawa’s “Red Beard” are more authentic. Zatoichi prioritizes drama and myth over quotidian truth.

Ultimately, the Zatoichi series walks a fascinating line between historical fact and fiction. It respects certain cultural truths—like the blind masseuse profession—while amping up dramatic elements such as gambling dens and confrontations in rural villages. The show’s charm partly lies in this blend: it feels historically flavored without being bound to documentary-level accuracy.

By framing these nuances, fans and history lovers alike can dig deeper and appreciate Zatoichi not just as thrilling entertainment, but also as a creative retelling inspired by Japan’s rich historical tapestry.

So the next time Zatoichi deftly detects loaded dice with his fingertips or navigates a village brimming with clandestine fights, remember: history lends its brushstrokes, but filmmakers wield the paintbrush for storytelling brilliance.