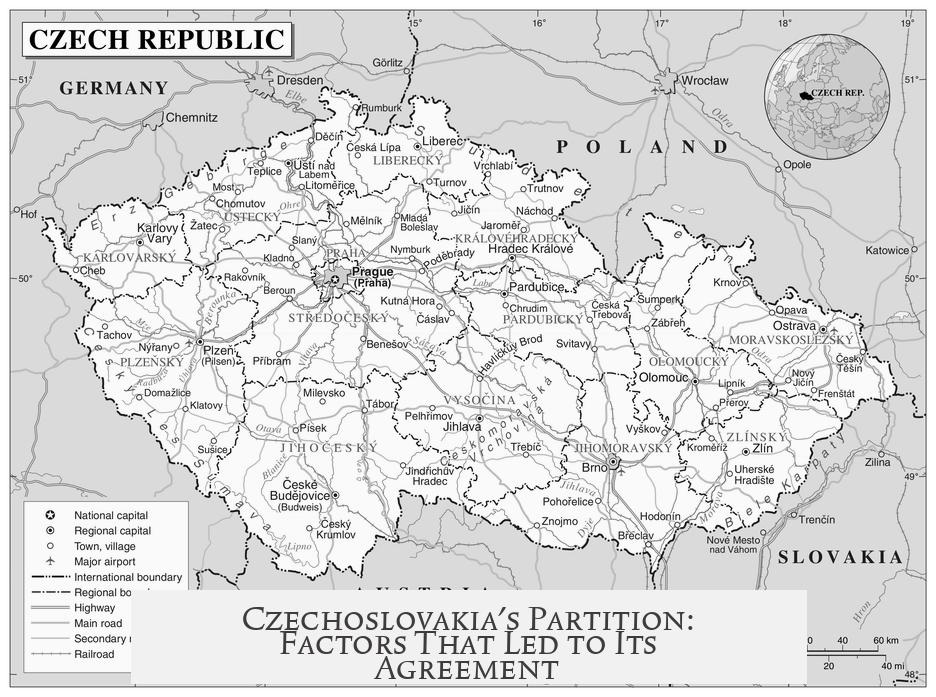

Czechoslovakia agreed to be partitioned primarily because it was excluded from key negotiations, faced immense pressure from Britain and France, and confronted internal divisions that undermined its ability to resist German demands. It did not so much agree voluntarily as accept an imposed decision under duress and severe strategic constraints.

Before the Munich Conference in September 1938, leaders of Britain, France, Germany, and Italy met to decide the fate of Czechoslovakia. The Czechoslovak representatives were present in Munich but were deliberately excluded from the core discussions. This exclusion meant they could neither influence nor challenge the agreement. Britain and France essentially forced Czechoslovakia to choose between a practically unsupported war against Germany or accepting the loss of territory to avoid immediate conflict.

This extreme pressure left Czechoslovakia with little real choice. The alternative was a war without allies, which was highly unrealistic given Germany’s military strength and Czechoslovakia’s relative isolation. Consequently, Czechoslovakia took the “bitter pill” of ceding the Sudetenland despite knowing it entailed severe risks.

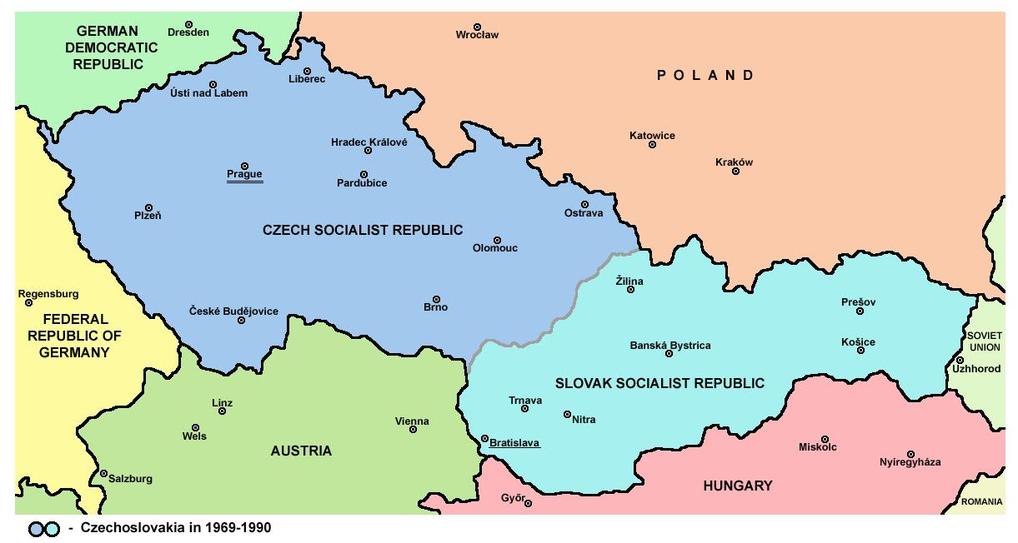

The Sudetenland was not just any territory. It was a mountainous, heavily fortified border region critical for Czechoslovakia’s defense. Surrendering this land removed key fortifications and natural barriers that protected the country from German military advances. Experts view forcing Czechoslovakia to relinquish the Sudetenland as a strategic blunder since it weakened the country’s defensive posture dramatically.

The policy behind the Munich Agreement was appeasement, mainly driven by British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. He believed that conceding the Sudetenland might satisfy Hitler’s expansionist aims and prevent a wider war in Europe. The deal included hopes for an international commission to supervise further territorial claims. As history shows, appeasement failed to halt German aggression; instead, it emboldened Hitler and led to further invasions.

Internally, Czechoslovakia was destabilized by a significant German-speaking minority. Around 22% of Czechoslovakia’s population was ethnic German. Many of these were influential in politics, business, and, to a lesser degree, the military. This minority included large urban and industrial elites who sympathized with or actively supported Nazi goals.

The Sudeten German Party, representing ethnic Germans, was a powerful political force with about 1.3 million members—roughly 40% of all ethnic Germans in Czechoslovakia. By the late 1930s, the party endorsed Nazi calls for the disintegration of Czechoslovakia. They commanded overwhelming electoral support within those regions, often exceeding 85% of votes from ethnic Germans.

This political and social fracture significantly complicated Czechoslovakia’s capacity to mount a coherent defense. Many ethnic Germans were likely to side with the invading German army, undermining loyalty within Czechoslovakia’s borders. Estimates suggest around 15-18% of the total national population actively or passively favored Nazi ambitions, a substantial internal security issue.

Furthermore, ethnic Germans participated in paramilitary groups like the *Ordnungsdienst*, aligned with the Sudeten German Party. Despite government crackdowns in 1938, these groups destabilized regions along the border. They posed a fifth-column threat by weakening the defense and potentially aiding German military operations.

Thus, the internal politics of Czechoslovakia were deeply entwined with the external pressures it faced. The ethnic German minority’s politicization created conditions closer to internal conflict than simple international aggression. This dimension made a conventional military defense far more precarious than the simple comparison of armies and fortifications suggested.

In summary, Czechoslovakia “agreed” to partition under coercive, external diplomatic exclusion, strategic vulnerability, failed international support, and a complex internal ethnic divide supporting Germany.

- Excluded from key negotiations at Munich, Czechoslovakia was forced to accept terms without input.

- The Sudetenland’s loss removed critical defensive positions, weakening the country militarily.

- Appeasement aimed to prevent war, but it failed, leading to further German expansion.

- The large, politically active German-speaking minority undermined internal cohesion and security.

- Paramilitary groups and divided loyalties made military resistance more dangerous and less viable.

How Come Czechoslovakia Just Agreed to Be Partitioned?

Czechoslovakia’s agreement to partition in 1938 boils down to a harsh reality: the country was pressured and sidelined by powerful neighbors and internal ethnic turmoil, leaving them no real choice but to accept the dismemberment—otherwise, they faced isolated war against Germany.

Let’s unpack how this grim scenario unfolded, and why it wasn’t a mere case of waving the white flag but a forced hand shaped by ruthless geopolitics and internal fractures.

Cut Out of the Conversation: The Munich Conference Snub

Picture this: The great powers—Britain, France, Germany, and Italy—meet in Munich in September 1938 to decide the fate of Czechoslovakia’s Sudetenland. But who isn’t invited? The Czechoslovak representatives who were physically there. In a diplomatic facepalm of epic proportions, they stood by as decisions about their own land were hammered out behind closed doors.

Why this exclusion? The European powers aimed to prevent war between Germany and the West by appeasing Hitler. They pressured Czechoslovakia to either resist Germany alone, without any support, or accept the terms of territorial surrender. Forced into a corner, the Czechoslovak leadership swallowed the bitter pill of partition because—let’s be honest—facing Nazi Germany by themselves was suicidal.

This was no honest negotiation. It was a diplomatic ambush. Facing the stark choice of war or territorial loss, Czech leaders chose the latter.

The Strategic Price of Losing the Sudetenland

The Sudetenland wasn’t just some random patch of land. It was a natural fortress: mountainous and heavily fortified, it was Czechoslovakia’s first line of defense against a German invasion.

Giving up the Sudetenland was a strategic blunder of monumental scale. Without it, Czechoslovakia was like a castle without a moat, vulnerable and exposed. Yet, despite its importance, this vital region was handed over without the Czechoslovakians’ input. That’s like giving away your security system because your neighbors said so—what could possibly go wrong?

Appeasement: A Hope That Backfired Spectacularly

British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s policy was simple—give Hitler some land and maybe, just maybe, he stops marching. The Munich Agreement was the embodiment of this hope. Chamberlain spoke of “peace for our time,” confident that allowing Germany to take the Sudetenland would satiate its appetite, with international safeguards poised to handle disputed areas afterward.

We know now how that worked out. Not at all. Germany didn’t stop; it invaded the rest of Czechoslovakia less than six months later. Munich became the textbook example of appeasement’s failure—a diplomatic lesson carved in stone.

Internal Instability: The German Minority Within

Here’s a twist often overlooked: Czechoslovakia’s troubles weren’t just external—they were internal. About 22% of its population was ethnic German, many of whom lived in the Sudetenland and held considerable sway in politics, industry, and even parts of the military.

Many of these German-speaking Czechs supported Hitler’s National Socialism. The Sudeten German Party, aligned with Nazi ideology, controlled vast support among these communities—over 85% of ethnic Germans in 1938 voted for them in some regions. These folks wanted to break away and join Germany.

How does this matter? In any hypothetical war, a significant chunk of the population might side with the invading Germans. This internal division was a ticking time bomb, severely complicating Czechoslovakia’s ability to defend itself.

The situation gets more tangled: paramilitary groups like the Ordnungsdienst, formed from pro-Nazi Sudeten Germans, were active within Czechoslovakia. Although the government cracked down on them, their presence destabilized border defenses and posed threats inside the country.

This internal ethnic conflict turned defense into a nightmare. Had Czechoslovakia chosen war, they would have battled not just an external army but an armed faction within their own borders.

The Bigger Picture: A Complicated, Coerced Decision

So why did Czechoslovakia just agree to partition? They didn’t have the luxury of a choice. They faced exclusion from high-stakes negotiations. They were pressured into acquiescence by Britain and France, who refused to fight alongside them. Their militarily vital territory was handed over to Germany without consultation.

Internally, their own ethnic German minority, powerful and pro-Nazi, undermined their unity and defense, making resistance even riskier. Their strategic position collapsed overnight, and their foreign allies weren’t stepping up.

It’s a bitter cocktail. Czechoslovakia’s leadership took the cold, hard look at reality and made the agonizing decision to accept partition—an act of survival, not cowardice.

Lessons from the Czechoslovak Partition

- Diplomatic inclusion matters: Excluding a nation from talks about its own future is not just rude, it’s reckless.

- Strategic geography counts: Losing fortified borderlands weakens national defense at a critical moment.

- Ethnic tensions can fracture states: Internal minorities with divided loyalties complicate national security immensely.

- Appeasement rarely works: Giving aggressors what they want may only embolden them further.

Could Czechoslovakia have stood up to Hitler without this partition? The odds were stacked heavily against them. Their own population’s divided loyalties and abandonment by allies left them in a trap. The outcome wasn’t just dictated by external force, but by a treacherous maze of political exclusion and ethnic strife.

So, next time you ponder why Czechoslovakia “just agreed” to be partitioned, remember: it wasn’t just a polite nod—It was the hardest, most forced decision made under brutal pressure and impossible odds.

Why wasn’t Czechoslovakia involved in the Munich Agreement talks?

Czechoslovakian representatives were excluded from the Munich conference. The major powers held emergency meetings without their input. They faced a choice: fight Germany alone without allies or accept the partition.

What made losing the Sudetenland strategically so damaging?

The Sudetenland was a fortified region protecting Czechoslovakia. Giving it away removed a key defensive area. The loss happened without the country’s consent, weakening its security.

Did the policy of appeasement influence Czechoslovakia’s partition?

Yes. Britain and France hoped conceding territory would satisfy Germany. The Munich Agreement was meant to avoid war but ultimately failed, emboldening further German expansion.

How did the German minority inside Czechoslovakia affect its ability to resist partition?

About 22% of Czechoslovakia’s population was German-speaking, many supporting Hitler. Their presence undermined national unity and defense, as some sided with Germany during the crisis.

Could Czechoslovakia realistically defend itself against Germany at that time?

Internal divisions and pro-Nazi German paramilitaries weakened Czechoslovakia’s position. Without support from allies, fighting a war would have been difficult and risky, influencing the decision to accept partition.