Skulls appear frequently in Mesoamerican art due to their deep association with the cycle of life, death, and resurrection, their role as symbols of power, and their continuing religious significance.

One primary reason is the resurrection cycle rooted in Mesoamerican mythology. Skulls symbolize not only death but also regeneration and rebirth. The tzompantli or skull racks visually represent this idea, sometimes described as “skull trees,” embodying the link between death and new life.

The Popol Vuh, a foundational Maya text, offers a vivid example. It tells the story of Hun Hunaphu and his twin who are decapitated by underworld lords and whose heads become part of a calabash tree. This tree then bears fruit that leads to the birth of the second Hero Twins, who eventually restore life and defeat the underworld. This myth deeply informs the artistic portrayal of skulls as part of a resurrection narrative.

Maya art frequently depicts these themes, like images showing the Maize God’s resurrection where a central skull figure is prominent. Archaeological sites reveal human bones beneath ball courts, and four-lobed motifs on court markers represent portals between worlds, reinforcing skull imagery as gateways linking life and death realms.

Another dimension is the skull as a display of power, especially in the Post-Classic period. The tzompantli functioned as a public demonstration of a ruler’s dominance. In earlier Classic Maya art, monuments featured detailed captures of elite enemies with their names. Later, skull racks became a less personalized but more dramatic representation of conquest and authority.

Modern Mesoamerican cultures maintain the skull’s significance through religious and folk practices. The skull remains a potent symbol connected to death’s power, offering protection, blessings, or vengeance. The Mexican figure Santísima Muerte (Holy Death) exemplifies this. Portrayed as a robed skeleton or skull, she embodies a folk saint blending indigenous beliefs with popular devotion, symbolizing death’s respected and formidable force.

| Aspect | Meaning of Skulls |

|---|---|

| Resurrection Cycle | Link between death and rebirth; embodied in tzompantli and Popol Vuh myths |

| Power Symbol | Displays ruler’s dominance; public demonstration of conquest |

| Religious Beliefs | Protective and petitioning icons in folk religion; represented by figures like Santísima Muerte |

- Skulls in Mesoamerican art symbolize death and resurrection intertwined.

- Tzompantli skull racks illustrate mythic cycles and political strength.

- Maya myths, especially the Popol Vuh, underpin skull symbolism.

- Modern folk traditions, such as Santísima Muerte, continue skull veneration.

Why Are Skulls So Popular in Mesoamerican Art?

Skulls in Mesoamerican art symbolize a deep connection to the cycle of life, death, and resurrection, embodying powerful myths and cultural values that go far beyond mere decoration. They tell a story about the world as the Mesoamericans understood it—a world where death and life dance endlessly together. But why the fascination with skulls? Let’s unpack this with some fascinating insights.

Imagine a world where death is not the end but a doorway. This belief shapes much of Mesoamerican art and culture. Skulls emerge as icons symbolizing this passage between life and death, and the promise of rebirth. The popular tzompantli, or “skull racks,” exemplify this profound symbolism.

The Resurrection Cycle: Life Sprouting from Death

At the core of the skull’s popularity lies the resurrection cycle. It’s not just about death—it’s about renewal. The skulls are part of a mythic narrative where life springs from the remnants of death. This is beautifully illustrated in the Popol Vuh, the sacred book of the K’iche’ Maya.

The Popol Vuh tells the story of Hun Hunaphu and his twin, who challenge the lords of the underworld in a ballgame—a contest involving both skill and fate. They lose, are decapitated, and their heads placed in a dead calabash tree. But here’s the twist: the tree miraculously grows fruit, and from this, new life arises.

In fact, Hun Hunaphu’s head, resting on the tree, spits into the hand of the young moon goddess, implanting life within her. She gives birth to the famous Hero Twins, who eventually defeat the underworld lords themselves. This myth isn’t just a tale; it’s a vivid representation of death followed by renewal, embodied by the skull.

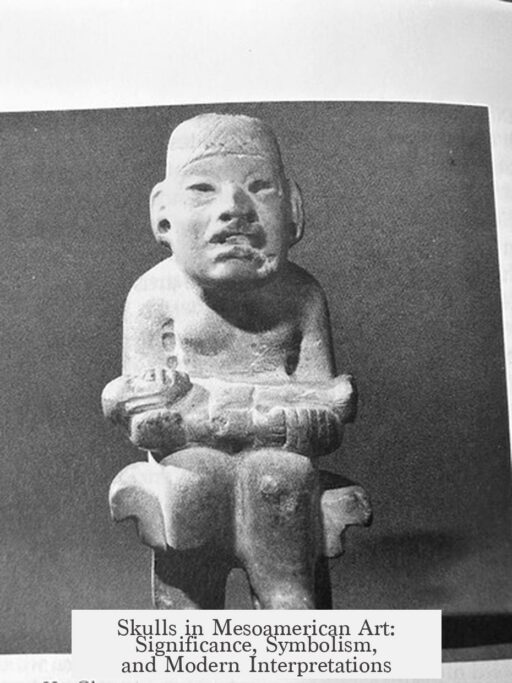

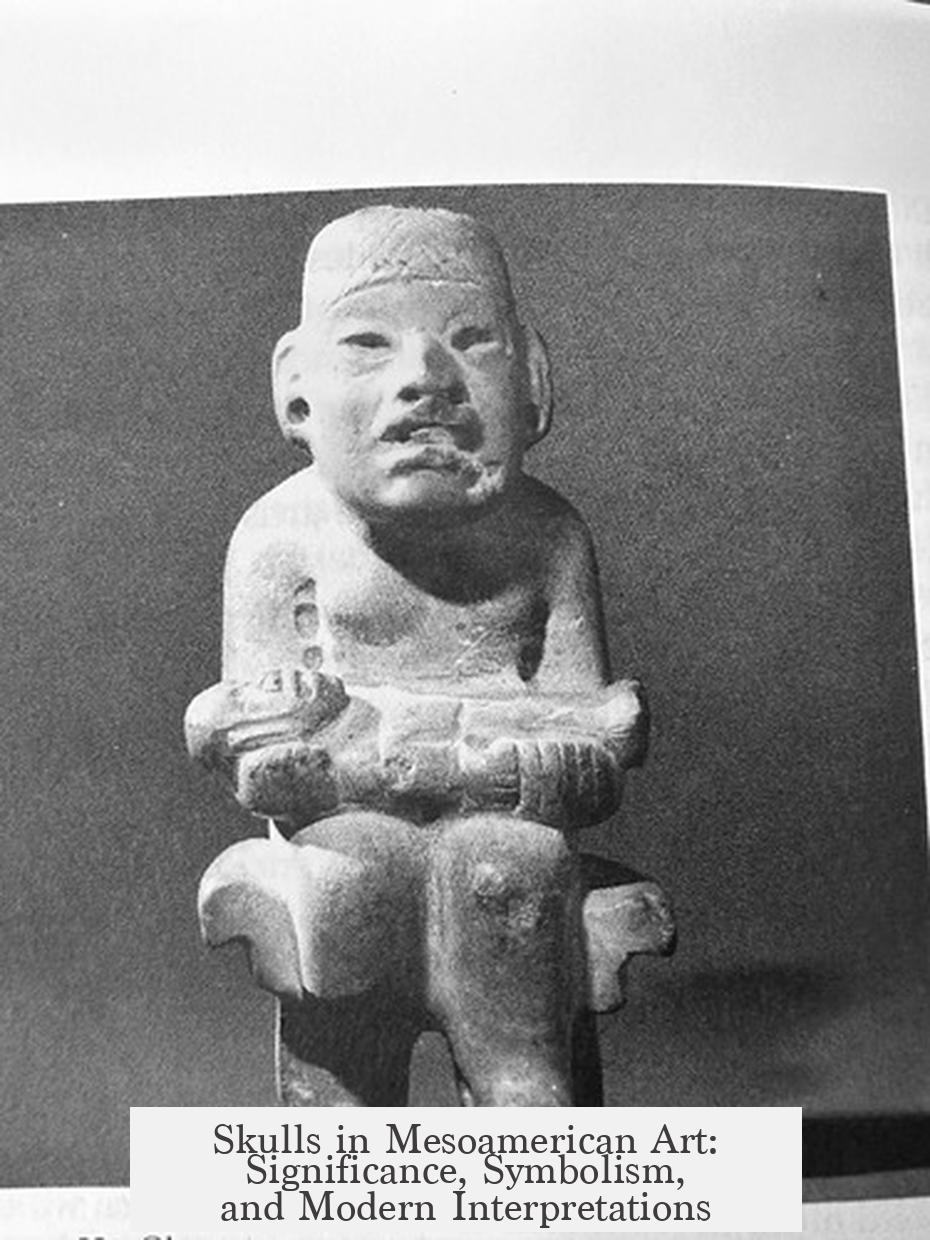

“The Maize God’s resurrection, often depicted with a central skull in Maya art, is a direct visual link to this mythic theme.” Maya Vase Depiction

You even see echoes of this resurrection cycle in real archaeological finds. Human bones buried beneath ball courts, and ballcourt markers featuring quatrefoil patterns, act as portals symbolizing passage between the living and the dead worlds. The skull is the bridge, the symbol linking these realms.

Tzompantli (Skull Racks): Power and Propaganda

Aside from spiritual meanings, skulls also serve as bold political statements. The tzompantli—rows of skulls displayed on racks—embody this dual role of fear and power.

During the Classic Maya period, rulers personally celebrated their victories with monuments showing captured elites, complete with names and titles. It was very personalized bragging. Later, in the Post-Classic era, the tzompantli emerged as a less personal but more intimidating display of power.

Imagine walking into a city and seeing an entire fence or rack lined with skulls. It’s a clear statement: “We have conquered and hold power over life and death.” The skulls aren’t just reminders of mortality—they’re trophies, a message of dominance.

Modern Mesoamerican Expressions: Death as a Protector and Guide

Skulls remain alive in modern Mesoamerican culture, but with twists in meaning. Instead of just symbols of power or death, they also hold protective, spiritual, and magical connotations.

Take the Mexican folk saint Santisima Muerte, or Holy Death. She’s often depicted as a skeleton or skull dressed in robes or even a wedding dress. People honor her not out of fear, but respect and belief in her power to grant favors, protection, and revenge.

This modern figure has roots in ancient Mesoamerican death deities, possibly Mayan. So the skull in today’s folk belief goes beyond the grave. It serves as a guardian, a spiritual force intertwined with everyday life.

So Why Are Skulls So Popular in Mesoamerican Art?

Because they mean something *profound*—death isn’t dark or final. It’s part of a much bigger story, where life, death, power, and myth interconnect. Skulls are keys to this story:

- They symbolize the resurrection cycle, embracing life through death.

- They represent political power and dominance through the tzompantli.

- They continue to connect communities spiritually in modern folk religions.

When you see a skull in Mesoamerican art, you’re not just looking at a bone. You’re glimpsing a worldview that embraces mortality with courage and creativity.

What Can We Learn From This?

Skulls teach us to confront the inevitable with meaning. Whether in ancient ballgames, towering skull racks, or modern shrines honoring Holy Death, they remind us that death is part of life’s grand dance.

Next time you encounter skull imagery—whether in a museum or on Day of the Dead altars—ask: What story of life, death, or power might this belong to?

This approach helps us appreciate Mesoamerican art on a deeper level—not as creepy or macabre, but as rich with symbolic meaning that continues to shape human culture.

In short, skulls in Mesoamerican art are popular because they are visual metaphors for resurrection, instruments of power, and spiritual protections, binding life and death in one powerful symbol that echoes from ancient times to today.