Monarchs came to be depicted wearing lots of ermine fur primarily from the medieval period onward as a symbol of purity, status, and wealth. The white ermine fur held strong symbolic value rooted in legends of its purity and moral significance. Its expense and luxurious feel made it ideal for royal garments, while sumptuary laws helped restrict its use to high-ranking nobility, reinforcing visual messages of authority and rank in royal portraiture.

Ermine fur gained prominence in royal imagery because of legends dating back to antiquity. Medieval bestiaries described the ermine (a small white weasel) as an animal that would rather die than soil its pristine white fur. According to a story from Claudius Aelianus’ On the Nature of Animals, hunters would encircle an ermine’s den with mud. The animal, unwilling to dirty its coat, would surrender. This story transformed ermine into a symbol of purity—both physical and moral.

Kings, queens, and religious figures such as popes adopted ermine to emphasize moral purity and incorruptibility. As robes trimmed or lined with ermine visibly conveyed such ideals, monarchs could project a sense of virtuous authority. This symbolism added depth to artistic portrayals, aligning power with moral superiority.

Besides symbolism, ermine fur’s rarity and softness contributed to its prestige. It was difficult to obtain and maintain. Its luxurious texture set it apart from other furs, marking wearers as individuals of exceptional rank and wealth. Thus, ermine functioned on multiple levels: as a material indicator of fortune and as a layered emblem of ethical and royal distinction.

Monarchs’ use of ermine also related to sumptuary laws which emerged in various medieval European countries. These laws regulated luxury clothing and furs, dictating who could wear certain fabrics and styles. For example, in England in 1363, a law specified that only the families of knights with rents above 200 marks could use certain furs. Esquires and gentlemen’s wives and daughters were prohibited from wearing ermine. These restrictions solidified ermine’s association with elite status. Its appearance in portraits became a clear visual cue of rank and nobility.

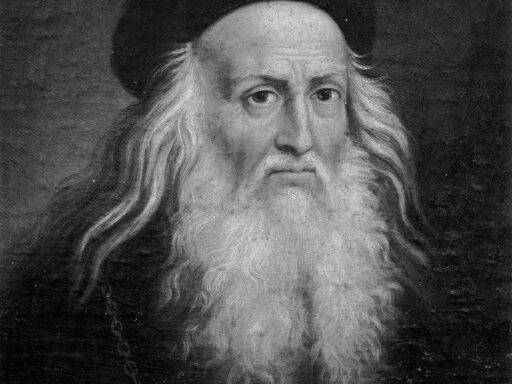

The depiction of monarchs in ermine fur sharply aligns with the evolution of royal portraiture. From ancient Egypt through the Greek and Roman eras, rulers were depicted with symbols reinforcing their divinity and authority. During the Middle Ages and Renaissance, portraits began incorporating more naturalistic elements but retained idealization. Icons like Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael rendered royals with careful attention to symbols of power.

By the 17th and 18th centuries, court painters such as Anthony van Dyck in England and Peter Lely incorporated ermine garments to signal prestige in official portraits. These images were not just art but instruments of political messaging, displaying royal legitimacy and dignity. This trend continued with photography in the 19th and 20th centuries, where formal royal portraits preserved the tradition of luxurious dress as a status marker.

In practice, ermine fur in royal portraiture served to:

- Signal morally pure leadership and incorruptibility.

- Showcase economic power through access to expensive, luxurious materials.

- Reinforce social hierarchy by restricting use via laws and customs.

- Enhance the visual language of authority and grandeur in official representations.

These factors explain why monarchs wore and were depicted wearing ermine fur in abundance. It combined deep symbolism, economic privilege, legal exclusivity, and artistic tradition into a single potent motif.

Key takeaways:

- Ermine fur symbolizes purity, originating from medieval legends of the animal’s refusal to soil its white coat.

- It demonstrates wealth and rank due to its luxury and expense.

- Sumptuary laws limited ermine’s use to high-ranking nobles, reinforcing social hierarchy.

- Royal portraiture employed ermine to visually communicate authority, legitimacy, and moral virtue.

- Its depiction became a tradition from the medieval period through modern royal portraits.